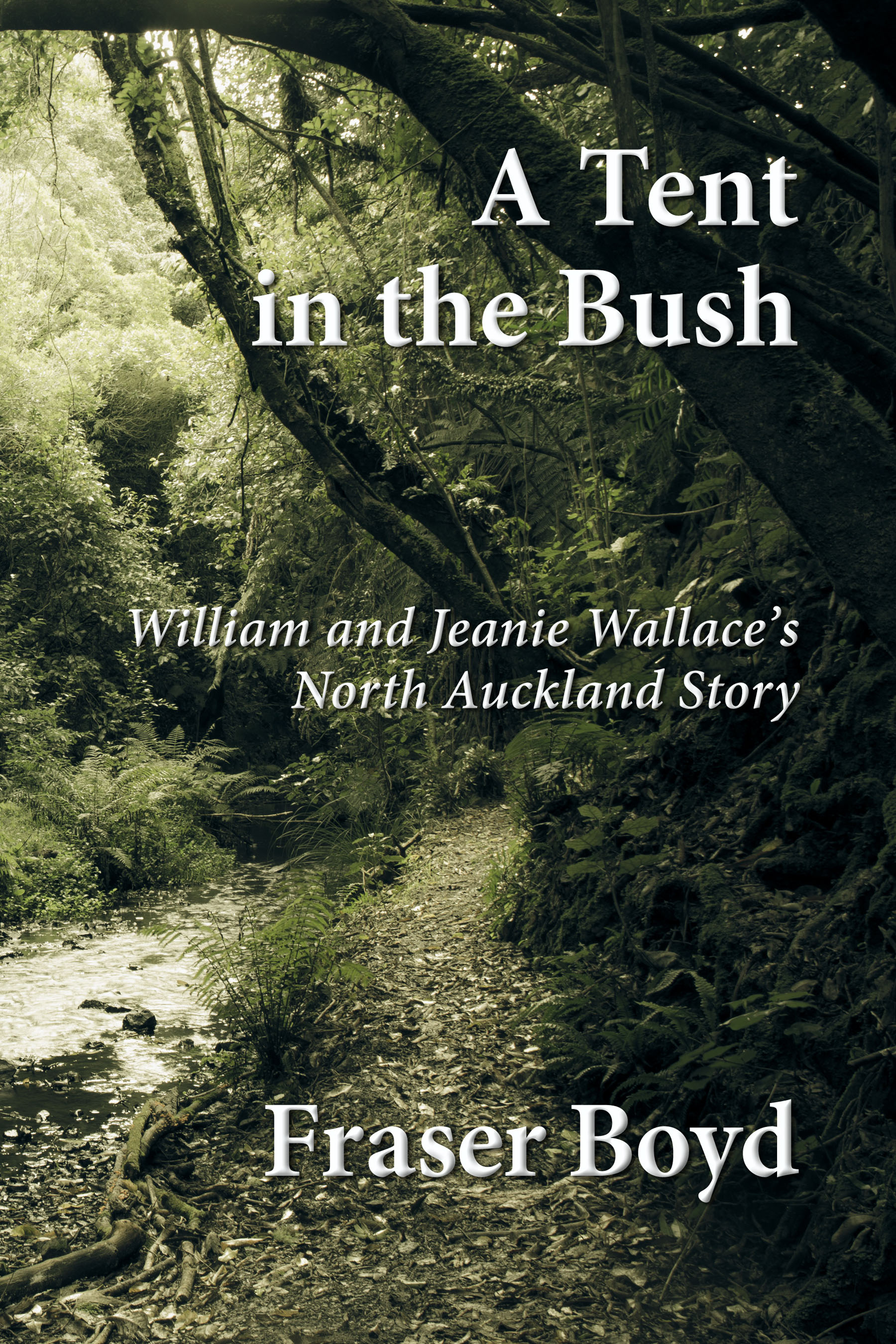

A Tent in the Bush

William and Jeanie Wallaces

North Auckland Story

Fraser Boyd

Copyright 2017 Fraser Boyd

All rights reserved.

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

ePub edition

ISBN 978-1-927260-63-0

Acknowledgements

No book is the result of one persons effort.

In this one I was helped immeasurably by my wife Margaret

and her sisters Dianne Wall and Dorothy Wallace,

and our daughter Sharon Regnaud, who encouraged me immensely

with her comment,

I like your style, Dad. Dont change it.

Philip Garside Publishing Ltd

PO Box 17160

Wellington 6147

New Zealand

books@pgpl.co.nz www.pgpl.co.nz

Front cover photograph:

Alexander GarsideGarside Imaging

Line drawings: Tent, Jeanie, William

by Rosemary Garside

Table of Contents

What We Know

We know a little more about the Wallaces than we knew about John and Mary White, the subjects of my previous book: Never to Return Home. But it remains cold, hard facts, not warmth and love, so this story is as much the product of imagination as the last one.

The Wallaces lived in Ireland until about 1852, when James and Eliza Wallace moved to Scotland. Students of the history of the two nations will have a fair idea of the historical background surrounding the mass migrations between the two countries at this time. I have sought to put a human face on it rather than a historical one, so I ask serious historians to forgive the licence I have taken.

All the Wallaces in this story existed in the historical periods in which they are placed. Almost all the other characters are imaginary. Similarly, the dates quoted are correct, at least to within a year or so.

Jeanie and William did lose a child in Scotland, very possibly the trigger for their move to New Zealand as I have portrayed it.

In New Zealand, the broad facts of family life are correct. Some of the characters (Taylor, Cherrie, Millington, Dr East, for example) are real historical figures, but the things I have reported them doing are likely, rather than factual. Cherrie did have extensive mining interests in North Auckland, and William Wallace had shares in his mines.

Others (the Pavlovics, Hopkinsons, the bank managers, for example) are products of my imagination, but are people we would like to have seen living around and helping a young couple trying to find their way in a strange country.

A few of the incidents are correct. William did lose his Mine Managers Certificate in a rubbish fire as reported, in fact the whole saga of the Certificate is broadly correct. He was a member of the Hikurangi Domain Board, and he did cut his second son out of his will, although we dont know why.

Jeanies headstone in an obelisk in Kaurihohore Cemetery, and William is buried with her, although no indication of that exists on the headstone.

Prologue

The newly arrived immigrants carried on down Queen Street, passing with hardly a pause, a drapery and a milliner, and came to the Chinese greengrocer they had heard about back in the hostel, although he had no name above his door. They trooped in, and at first sight saw that his shelves carried much what they had been used to cabbages, cauliflowers, potatoes, and onions. There were also some vegetables that they were not used to, so they first talked amongst themselves about a root which looked like an elongated purple potato. Amy, one of the single girls asked the greengrocer what it was. The best they could make from his pronunciation was cumela . The next question, was how to cook them, which created huge merriment as they tried to work out what the Chinese shopkeeper was saying. They were saved by a lady, (very much a lady, as Jeanie remarked to William later), who told them the correct pronunciation was kumara, and that you could boil it or bake it just like potatoes.

It is grown by the Maoris, in fact before the Europeans came it was their basic food, she said. It is very sweet and tasty. I use it a lot.

They also noticed what looked like a bunch of limp spinach.

Puha, their new friend told them, to be boiled like cabbage. It grows wild here, but mostly outside the town. I know it looks a bit limp, but it does cook up well, and is cheap. The Maoris harvest it and bring it in to sell.

They thanked her for her help, and one of the more adventurous suggested that they buy two kumaras, and a bunch of puha, and all share in a tasting at dinner time. So they put in a halfpenny each to pay for these new, exotic vegetables. They assumed that Janet and Mrs Johnson would know how to deal with them once they got them into the kitchen.

So they moved on down the street, past a gentlemens tailor and a stock feed shop to a butchers with the legend over his door George Wilson and son, Purveyors of Fine Meats.

There appeared to be no shortage of food in this place, but how would they learn to cook it? Their early explorations into eating would depend heavily on Mrs Johnson and Janet.

The Historical Context

In the late 1700s, landowners in the highlands of Scotland decided that they could farm more profitably if they had all of their land to themselves, rather than renting small parcels of land to impoverished tenant farmers. Because there were no laws about how landowners should treat their tenants, there was no redress when a tenant was evicted from the land his family had farmed for generations or from the home they had lived in for much the same length of time. After several generations of tenants, it was generally accepted, by the tenant families at least, that they had as many rights to the land as the landowners, provided that they paid their rents. Landowners, however, did not see it the same way. Many stories have been told of despairing husbands with weeping wives and children and their few pitiful possessions walking off down the highland roads with no idea where they might go or what they might now do to feed and clothe their families. Little help was forthcoming from family and friends because most of their friends and relatives were of the same class and in the same position. The only people who were certain of work were bailiffs and gamekeepers. Their role was, crudely put, to prevent people from occupying empty houses or poaching game to ensure their familys survival.

So people from the highlands flooded into the lowland cities. This had a major effect on the lowland economies as these desperate people who could not obtain work resorted to theft, poaching and, in the worst cases, serious violence just to survive.

A few had a little money, enough to get away in a boat to Ireland, where, it was said, there was greater opportunity. The Scots in Ireland, however, ultimately became a liability to the Irish. When the potato famine hit in the mid1850s, the Scots were the first to lose their jobs as the whole population struggled to eat. Was Ireland with its English landlords any better than Scotland, where landlords put their own countrymen off the land? For most of the Scots in Ireland, however, their heritage was never far below the surface. Being a Scot was possibly the only source of pride left to many of these displaced people.