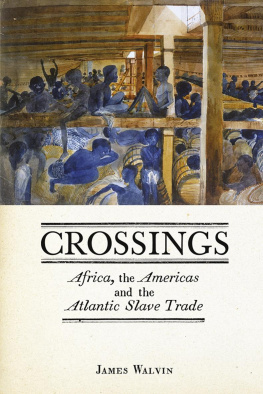

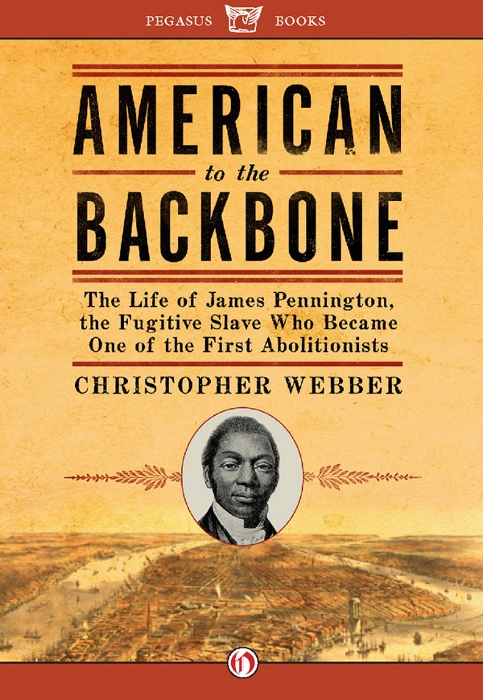

American

to the

BACKBONE

The Life of James Pennington, the Fugitive Slave Who Became One of the First Abolitionists

CHRISTOPHER WEBBER

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK

for

Harold Louis Wright

19291978

I am an american to the backbone ...

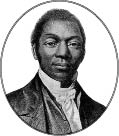

James W. C. Pennington

PREFACE

I t should be noted that certain spellings were inconsistent in mid-nineteenth century America, in particular such words as color/colour, labor/labour, etc. When English sources are quoted, the latter spelling is consistently used even if the speaker was an American, but in the United States both spellings were common. Practise/practice and defense/defence are other words inconsistently spelled in the various texts I have quoted. Whatever spelling was found in the original has been maintained. Among the most difficult matters in that respect is the term anti-slavery which appears sometimes as one word, sometimes as two, and sometimes with a hyphen. I have tried to replicate the original and to use the term with a hyphen myself. I dislike using [sic] but at times it seems necessary to show that the error was in the original. It might be noted also that when misspellings occur in quotations from James Pennington or anyone else, the error may well be with the original editor or typesetter.

The following abbreviations have been used in the footnotes:

BAA UDMBlack Abolitionist Archives, University of Detroit Mercy

BAPBlack Abolitionist Papers microfilm. The published version of the Black Abolitionist Papers is cited by its full name.

CAColored American

FDPFrederick Douglass Paper

INTRODUCTION

H e had been running for almost eight days and he was tired and hungry. He had been captured twice by slave catchers and escaped. The last food he had eaten was a brief meal provided by the slave catchers three days earlier. Aside from that, he had had only a loaf of bread, a dry ear of corn, and some green apples that had made him sick. He had slept in the woods, in cornfields and under a bridge. And now, north at last of the Mason-Dixon line, he had asked for work and been directed to the house of a Quaker named William Wright.

Standing outside the door that could open a new life to him, James Pembroke (who would later change his name to Pennington) knocked.

Seldom do two short sentences provide us such an opening into two radically different lives. We can hear them as Pembroke did, both as an invitation and a challenge. He never forgot those words. No white man had ever spoken to him before as one man to another. They opened up for him the possibility of a life in freedom. For the rest of his life, he would remember them also as a standard of caring for others that he should maintain himself. In those words we hear as well the voice of a man who had put his life at risk for principles derived from his faith. William Wright had made his home open to the needs of others; his life was as available to them as the food on his breakfast table. Such stories as theirs should be remembered and told, not least because biographies provide a means of expanding our lives by entering into the lives of others.

This misuse of thee (it should be thou) appears to be Penningtons mistake, as it appears throughout his writing. We will avoid using the notation [sic].

American

to the

BACKBONE

CHAPTER ONE

Finding Freedom

A s he stood in the slave quarters of Rockland plantation, six miles south of Hagerstown, Maryland, on a sunny afternoon in late October 1827, James Pembroke knew that this was the day that would change his life forever. He and the other members of his family had been beaten once too often. He could remain a slave no longer.

Pembroke reviewed once again the events that had led to his decision. He had seen his father mercilessly beaten for daring to suggest that he would willingly be sold to another owner if his master was dissatisfied with his work. He had been beaten himself when he happened to look up from his work and catch his masters eye. But it was when his master threatened Pembrokes mother with a beating that he decided he could take no more. That happened on a Tuesday. By Saturday he had made up his mind to flee. He rolled up a small bundle of clothes, hid it in a cave a little distance from the house, and decided to leave the next day, Sunday, October 28.

Pembroke, like most slaves in Maryland, was usually given the Sabbath as a day of rest. On the Rockland plantation church-going was not allowed, but slaves could travel a few miles to visit family members on other plantations if they wished. Thus it would not be unusual to see a slave walking along the highway, and Pembroke would be less likely to attract attention than on a work day. With many of his fellow slaves away, all was quiet as Pembroke thought over for one last time the alternatives he had been weighing for weeks.

On the negative side of the balance were the consequences to himself and his family. Should he fail, should he be captured and brought back, there was the certainty of the most severe caning he had ever experienced. He would, in addition, almost certainly be sold south, sold to a harsher master and transported to the cane and cotton fields of the Deep South where the average survival time in the heat and hard labor was a mere seven years. There was, as a result, always a need for more slaves on those plantations, and in Maryland, where the need for slaves was declining, slave owners had turned to breeding and

Not least of his concerns were the consequences for his family. They would be accused of having helped him, and how could they prove that they had not? They, too, could be beaten and sold off to a harsher life. But they might suffer whether his escape attempt was successful or not. They would be safe only if he stayed, and even so they would be beaten as usual when their owner was feeling ill-tempered. So those consequences, he had concluded, could not weigh against his plans.

All morning Pembroke had sat in the blacksmiths shop and thought it through yet again. Hope, fear, dread, terror, love, sorrow, and deep melancholy, he recalled, were mingled in my mind together. One thing he understood clearly: if his courage failed at this point and he failed to act, no better moment would ever come and he would be a slave for the rest of his life. As the days went by, the obstacles to flight would only become greater. He might soon have children of his own whom then he would be unwilling to leave. Even now he hated the thought of leaving his parents and brothers and sisters behind. Perhaps most difficult of all was the fact that he was so completely ignorant of the larger world. Although he had once lived in Hagerstown for two years as an apprentice stone mason, he had almost no knowledge at all of the world beyond that. He would be striking out for an unknown land in which he would know not a single human being and yet he would be forced to rely on those unknown individuals for his survival.

What little Pembroke knew of the world beyond the plantation had come from conversations overheard when he was an apprentice in Hagerstown, and the stories told by other slaves who passed on information by word of mouth on their Sabbath visits or as they were bought and sold from one plantation to another. Then, too, there were thousands of free African Americans in Maryland, some of whom had traveled to the north and had come back with stories to tell of their experience. Listening to them, Pembroke had learned that there was freedom in Pennsylvania and that Pennsylvania lay somewhere to the north. How far to the north Pennsylvania was, he had no idea. In fact, it was no further north from Hagerstown than Hagerstown was from his home. The border with Pennsylvania, the famous Mason-Dixon line, was only six or seven miles beyond Hagerstown and within easy reach for a young man in a hurry. Yet for all he knew it might have been a thousand miles away. The distance worried him, but he thought he was strong enough to survive or at least to attempt the journey. He was nineteen years old, sturdy and capable, with skills as a blacksmith and stone mason and carpenter. If ever there were a time to leave home, this was that time. He

Next page