Introduction

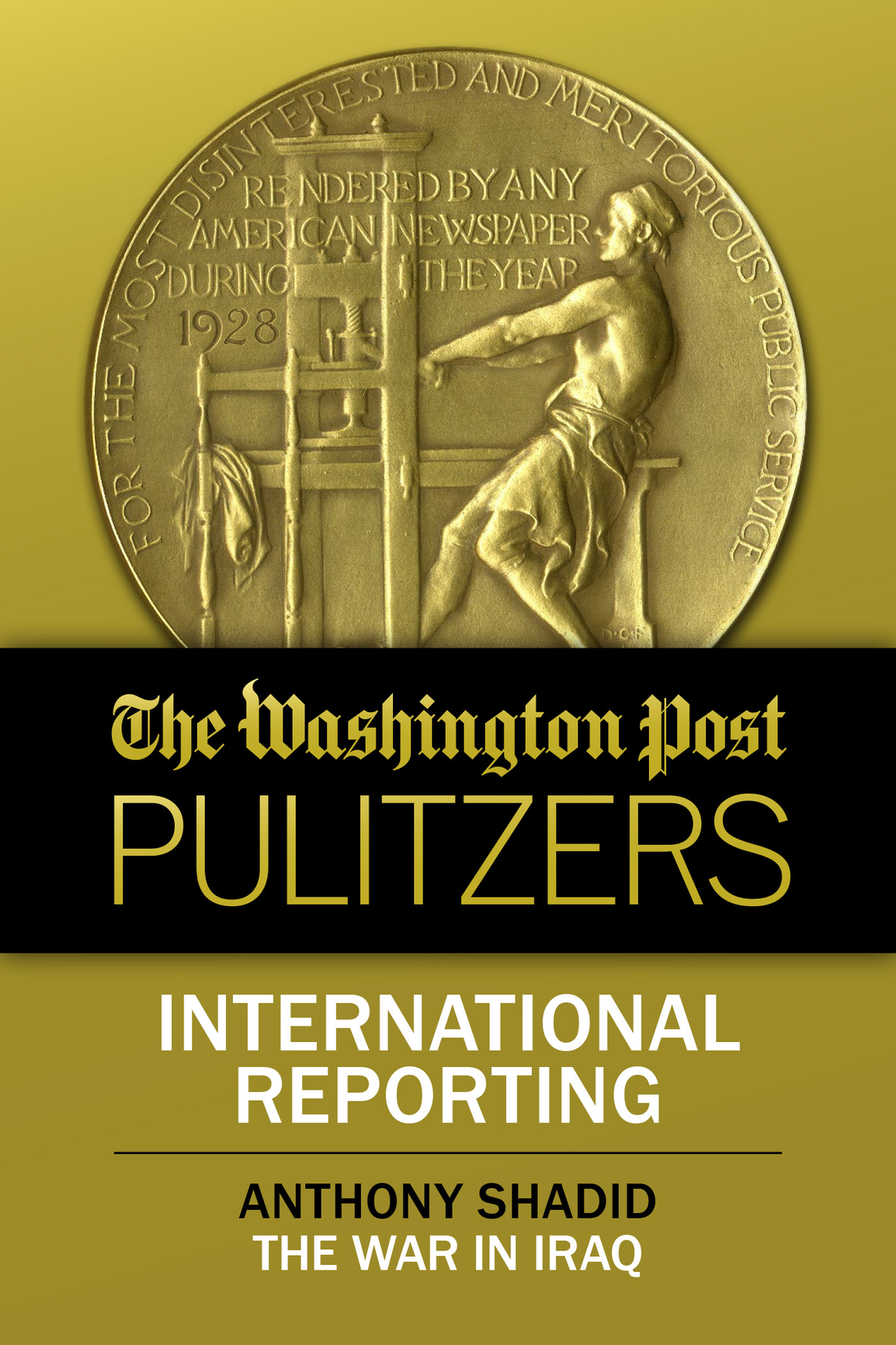

On the eve of the war in Iraq, as news organizations ordered correspondents to leave Baghdad for their safety, Anthony Shadid called his editor at home in Washington before dawn. His first words were, I am basically begging you to let me stay. There was no bravado in his voice. He described precautions he had taken, and then his conviction that what was about to occur would shake the Middle East to its core. Ive prepared for this story my whole career, he said. Please let me do this.

Over the next weeks, Shadids lyrical and poignant dispatches from Baghdad gave readers of The Washington Post a searing view of Iraqis experience of the war. Over the next months, his insightful reporting and original prose revealed hidden forces determining the direction of the U.S. occupation and the future of Iraq. Over the next few years, in scores of front-page stories, he demonstrated how a lone reporter with a mission to inform and exceptional skill, courage, and stamina can uncover the human factors at the center of a conflict, and change the publics understanding of a major event.

Shadid, a Lebanese American from Oklahoma, is one of only a handful of foreign correspondents who has won the Pulitzer Prize twice. He won once in 2004 for chronicling the beginning of the war, and again in 2010 as the United States departed and Iraqs people and leaders struggled to deal with the legacy of war and to shape the nations future.

From the first explosions in Baghdad, Shadids stories stood alone. While common Iraqis were invisible in most media coverage of the shock and awe campaign, they were the focus of Shadids work. His account of a family living beneath the bombs was striking for its intimacy, and for giving voice to Iraqis complex emotions about the war. His spot stories on civilian casualties were classic war correspondence in their richness of detail and unvarnished description. His story of the burial of 14-year-old Arkan Daif was perhaps the most evocative and meticulously reported story of a civilian death produced during the conflict. Each of these stories required courage in both the reporting and writing. Without glossing over the confusion and contradictions of wartime, the stories bore witness by being grounded in first-hand observation and transparent, striking prose. Nothing came closer to putting readers there.

Shadids stories gave readers unmatched access to Iraqis lives, a reflection of his access. The son of Lebanese immigrants to the United States, he drew on fluent Arabic and a decades experience reporting in the Middle East. This included combat experience in 2002 he was shot and seriously wounded while covering the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Roaming Baghdad at the height of the bombing, he was able to cross government checkpoints undetected and visit Iraqis in their homes. He also gained the complicity of his official minder, or government escort. The minder looked the other way while Shadid conducted unsupervised interviews, and introduced him to Baath Party members opposed to Saddam Hussein.

But Shadids stories did more than show the human side of the war; they were a guide to its complex aftermath. He captured the central role of religious belief in shaping Iraqis views of the war, and the ambivalence many felt toward the United States despite their loathing of Hussein. His coverage created a portrait haunting to read months later of people grateful for freedom but wary of U.S. forces.

His run of war correspondence measured by reader response and its impact on the papers presentation of the conflict was as influential as any in The Posts history.

He changed the way we saw Iraq, Egypt, Syria over the last, crucial decade, said Phil Bennett, the former managing editor of The Post who worked closely with Shadid. There is no one to replace him.

Marty Baron, editor of the Boston Globe, for which Shadid worked before joining The Post in 2003, recalled rushing to Israel in 2002 after Shadid, then a Globe reporter, was shot while covering demonstrations on the West Bank.

It was amazing, seeing him in the hospital. Here was a person that, despite what happened to him, was still remarkably positive about things, demonstrated a real eagerness to get out of the hospital, get back in the field, said Baron. It was clear his wounds were not going to stop him, even though it looked like he was going to have severely limited mobility in at least one of his shoulders. He was amazingly resilient. He had such a love for the story of the region, and a passion for telling that story.

Steve Fainaru, a former Post reporter who worked extensively with Shadid in Iraq and also won a Pulitzer for his own work, recalled him as the best journalist Id ever seen without any question.

He wrote poetry on deadline, Fainaru said. What made him so great as a journalist [was that] he was able to somehow find compassion and empathy in everything he touched and wrote about.

Anthony Shadids magic was reporting, said former Post foreign editor David Hoffman, who also worked closely with Shadid.

Everywhere he went, he absorbed stories about people and their trials. Once when he was working on his second book, Night Draws Near, we had a long talk about how to do it. And I saw how he did it: bundles of notebooks from Iraq, thousands of pages stories, impressions, smells and sights. One young girls diary about those terrible days of war became part of the book, but the diary came to life in his hands.

Hoffman recalled a memo Shadid wrote in early 2006 about wanting to probe what would happen when the frozen leadership of Arab countries cracked.

He wrote: To me, this moment is no less sweeping than that experienced by Eastern Europe in the aftermath of the Cold War.

And he was right, said Hoffman. The Arab Spring was what he had been waiting for.

But Shadids own story ends as tragically as many of his dispatches did.

In 2012, after he left the Post for the New York Times, Shadid had been reporting in Syria for a week on rebels battling the regime of Bashar al-Assad. Tyler Hicks, a New York Times photographer who was accompanying Shadid, said Shadid had asthma and carried medication with him. Shadid began to exhibit symptoms, and they escalated into what became a fatal attack, according to Hickss account.

The two men had entered the country in defiance of a Syrian ban on Western reporters, sneaking in at night under barbed wire. They were met by guides on horseback, and Shadid apparently had an adverse reaction to the horses. A week later, as they made their way out, he reacted to the horses again. I stood next to him and asked if he was okay, and then he collapsed, Hicks said. Hicks attempted to revive his colleague and then carried him across the border into Turkey. The news of Shadids death sent shock waves through newsrooms in New York, Boston and Washington, where journalists who had worked with Shadid at those cities three leading newspapers recalled a colleague of deep intellect, enormous generosity and a well-tuned, ironic sense of humor. It was an ironic end for a man who placed himself in the path of danger countless times.