Copyright 2012 by Anthony Shadid

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shadid, Anthony.

House of stone: a memoir of home, family, and a lost Middle East / Anthony Shadid.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-13466-6 (hardback)

1. FamiliesLebanon. 2. HomeLebanonHistory. 3. LebanonEmigration and immigrationSocial aspects. 4. Middle EastSocial conditions. I. Title.

HQ663.9.S53 2012

306.0956dc23

2011036906

Book design by Brian Moore

To my wife Nada, daughter Laila, and son Malik

And to Jedeidet Marjayoun, as it was and will always be

The true Vienna lover lives on borrowed memories. With a bittersweetpang of nostalgia he remembers things he never knew. TheVienna that is, is as nice a town as ever there was. But the Viennathat never was is the grandest city ever.

Orson Welles, Vienna (1968)

Introduction: Bayt

The Arabic language evolved slowly across the millennia, leaving little undefined, no nuance shaded. Bayt translates literally as house, but its connotations resonate beyond rooms and walls, summoning longings gathered about family and home. In the Middle East, bayt is sacred. Empires fall. Nations topple. Borders may shift or be realigned. Old loyalties may dissolve or, without warning, be altered. Home, whether it be structure or familiar ground, is, finally, the identity that does not fade.

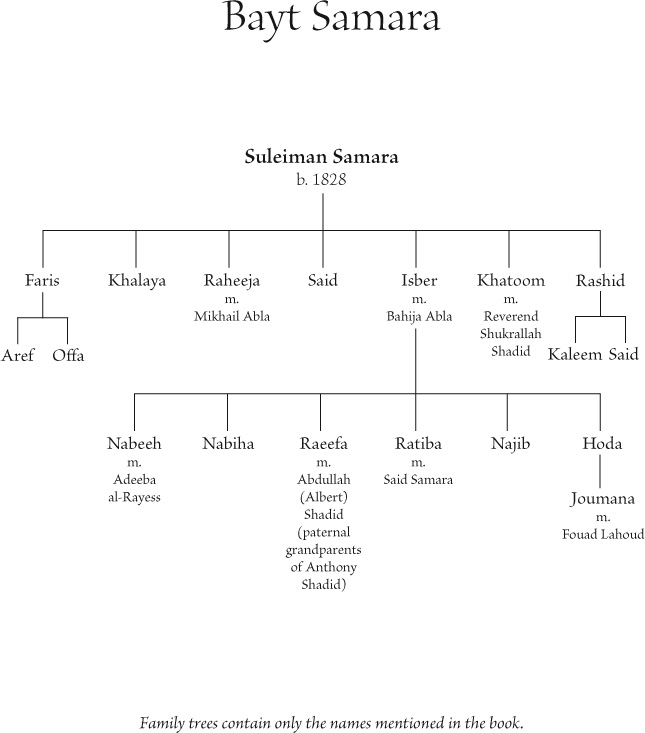

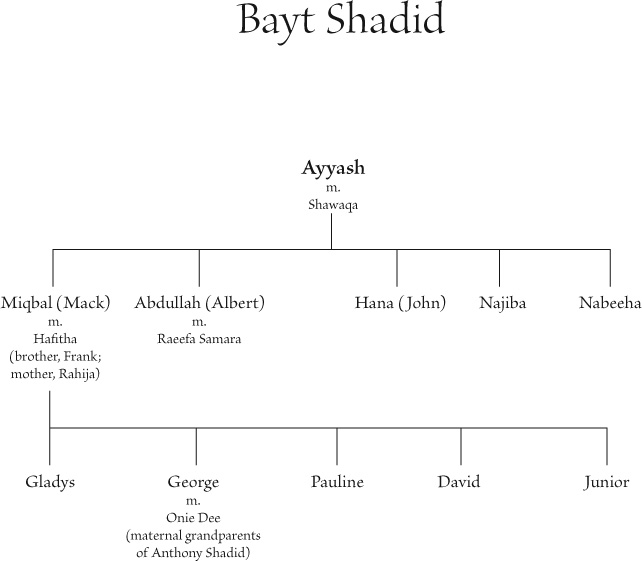

I n old Marjayoun, in what is now Lebanon, Isber Samara left a house that never demanded we stay or enter at all. It would simply be waiting, if shelter was necessary. Isber Samara left it for us, his family, to join us with the past, to sustain us, to be the setting for stories. After years of trying to piece together Isbers tale, I like to imagine his life in the place where the fields of the Houran stretched farther than even the dreamer he wasa rich man born of a poor boys laborscould grasp.

In an old photo handed down, Isber Samaras heavy-seeming shoulders suggest the approach of the old man he would never become, but his expression retains a hint of mischief some might call youthful. More striking than handsome, his face is weathered from sun and wind, but his eyes are a remarkable Yemeni blue, rare among the Semitic browns of his landscape. Though the father of six, he seems beyond proper grooming. His hair, apparently reddish, is tousled; his mustache resembles an overgrown scattering of brush. Out to prove himself since he was a boy, Isber would one day come to believe that he had.

By the time the photo of Isber and his family was taken, he was forty or so, but I am drawn more to the Isber that he becamea father, no longer so ambitious, parted from his children, whom he sent off to America to save their lives. I wonder if he pictured them and their descendantssons and daughters, grandsons and granddaughters, on and onmoving through lives as unpredictable as his. Did he see us in years ahead, adrift, climbing the cracked steps and opening his doors?

At Isbers, the traveler is welcome, befitting the Bedouin tradition of hospitality that he inherited. The olive and plum trees stand waiting at this house of stone and tile, completed after World War I. The place remains in our old town where war has often stopped time and, like an image reflected in clear water, lingers as well in the minds of my family. We are a clan who never quite arrived home, a closely knit circle whose previous generations were displaced during the abandonment of our country decades ago. When we think of home, as origin and place, our thoughts turn to Isbers house.

Built on a hill, the place speaks of things Levantine and of a way of life to which Isber Samara aspired. It recalls a lost era of openness, before the Ottoman Empire fell, when all sorts drifted through homelands shared by all. The residence stands in Hayy al-Serail, a neighborhood once as fine as any in the region, an enclave of limestone, pointed arches, and red tile roofs. The tiles here were imported from Marseilles and, in the 1800s, suggested international connections and cosmopolitan fashionableness. They were as emblematic of the style of the Levant as the tarbush hats worn by the Ottoman gentlemen who lived in the Hayy, where the silver was always polished and the coffee came often in the afternoon. Old patriarchsancient and dusty as the setteeswiped rheumy eyes with monogrammed handkerchiefs. Sons replaced fathers, carrying on treasured family names. Isber was not one so favored.

In a place and time not known for self-invention, Isber created Isber. His extended family, not noteworthy, consisted of less than twenty houses. His furniture, though expensive and imported from Syria, was as recently acquired as his fortune, and his house stood out not just because of its newness. It was a place built with the labor of a rough-hewn merchant whose eye was distracted from accounts only by his wife, Bahija. It serves as a reminder of a period of rare cultivation and unimaginable tragedy; it announces what a well-intentioned but imperfect man can make of life. Isbers creation speaks of what he loved and what sustained him; it reminds us that everyday places say much, quietly. The double doors of the entrance are tall and wide for men like Isber, not types to be shut in.

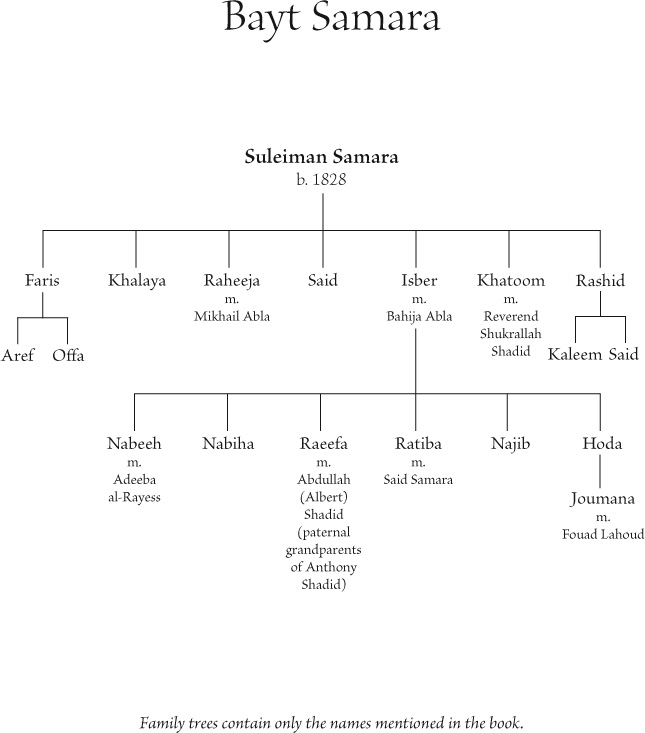

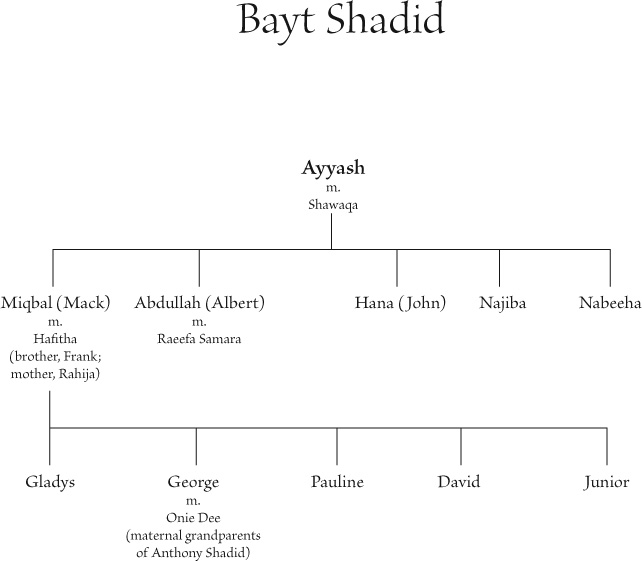

Isber, whose daughter Raeefa gave birth to my father, was my great-grandfather. I came of age with remembrances that conjured him back to life, tales that made him real and transported my family to his world, a stop gone missing on recent maps: Jedeidet Marjayoun. This is the way my family refers to our town, our hometown. Never Jedeida, never just Marjayoun. We use the full name, a bow of respect, since for us the place was the beginning. It was bayt, where we came to be.

Settled by my forebears, Marjayoun was once an entrept perched along routes of trade plied by Christians, Muslims, and Jews which stitched together the tapestry of an older Middle East. It was, in essence, a gatewayto Sidon, on the Mediterranean, and Damascus, beyond Mount Hermon; to Jerusalem, in historic Palestine; and to Baalbek, the site of an ancient Roman town. As such, this was a place as cosmopolitan as the countryside offered. Its learning and sophistication radiated across the region.

Yet lingering in small places is not in favor now; they no longer seem to fit the world. Yes, Marjayoun is fading, as it has been for decades. It can no longer promise the attraction of market Fridays, when all turned out in their finerywomen in dresses from Damascus, gentlemen with gleaming pocket watches brought from America. At night, there are only flickering lights, which even a desperate traveler could overlook. In the Saha, or town square, there are dusty thingsmarked down for decadesfor sale. No merchants shine counters, or offer sherbets made from snow, or sell exotic tobaccos. The cranky sheikh who filled prescriptions, if he cared to, is no more. The town no longer looks out to the world, and it is far from kept up. Everywhere it is scattered with bits and pieces, newspapers from other decades, odd things old people save. Of course, no roads run through Marjayoun anymore. A town whose reach once spanned historic Syria, grasping Arish in the faraway Sinai Peninsula of Egypt before extending, yet farther, to the confluence of the Blue and the White Niles, now stretches only a mile or so down its main thoroughfare.

Next page