I have endeavoured to fairly represent the artists, dealers, galleries, collectors and others involved in the matters covered in this book, and to seek permission where possible for use of sensitive content. In some cases, parties were invited to read a draft to confirm and/or clarify details. In other cases the person or organisation did not want to engage in dialogue or was deceased. If you have new information, please contact the editorial team at Awa Press. All currency in the book is given in New Zealand dollars unless stated otherwise. All dimensions are in height before width.

Foreword

I CALL IT THE TREASURE HUNT INSTINCT. We all have it: the desire to find what is lost, to learn what is secret, to see what is hidden, to recover what has vanished. Its no surprise that publishers love to stud their thriller titles with these key words in fact, it once occurred to me to name one of my books Lost, Secret, Hidden. Thats the sort of book I would buy without bothering to read what it was about.

This is one of the great appeals of a crime story, whether factual or fictitious. It begins with a question. Something has happened, and we dont know why or how or who did it, or some combination of the above. And something has disappeared, whether an object or a person or a perpetrator. When I teach, I encourage writers to prompt questions in their readers, and then intentionally delay the answer to draw them along. Mysteries and police procedurals do this by their very nature. And when, on our path to answering the questions posed in the crime, we are drawn through an exotic world this is all the more enticing.

The world of art crime intrigues me for just this reason. I was always entranced by art and the opaque, glamorous universe of collectors, galleries, museums, conservators, curators and experts that wealthy, intelligent, often fraught and sometimes corrupt landscape. This realm is populated by larger than life characters who would be difficult to believe as plausible in a work of fiction. An Irish traveller who is also a bare-knuckle boxing champion helps recover priceless old masters. An oddball loner makes lousy forgeries and passes them off to at least forty galleries, but gives them as gifts, asking nothing in return and seems not to have broken the law in doing so. An Iranian millionaire art collector, with a lavish collection in his home, is caught slicing rare prints and maps out of books at the British Library. Can any of this be real?

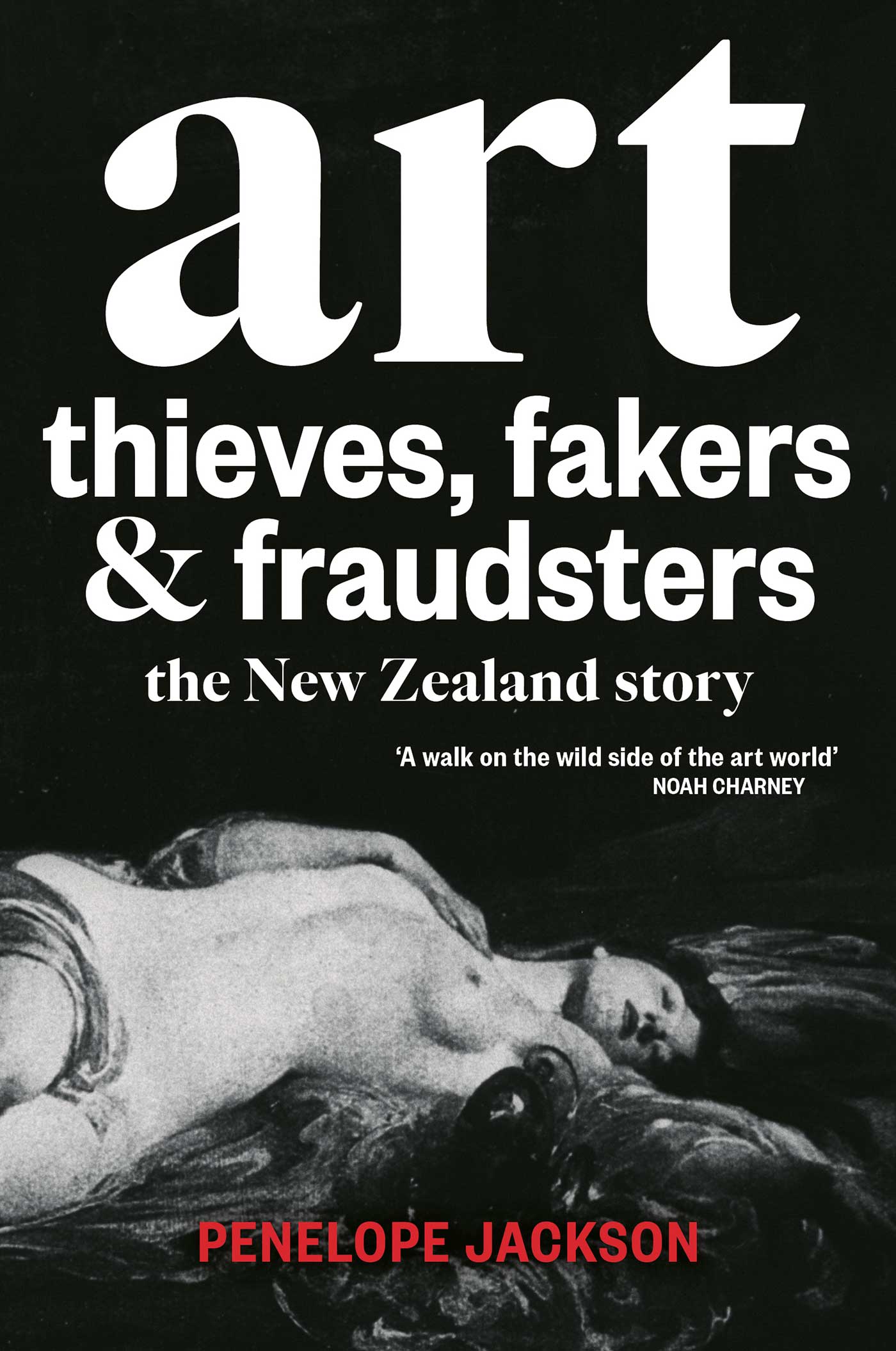

Combine true crime with the pizzazz of the art world, throw in a population of Dickensian caricatures who happen to actually exist, and you have the makings of a sensational book. And this is one such book, swinging the telescope away from the often trod paths of art crime in the United States and Europe (and, lately, the Levant), on to the islands of New Zealand.

There should be a book like this for all 198 nations on the planet: every country has its share of colourful and important stories of crimes involving art. But the truth is that art crime has been largely overlooked until recently, often dismissed as concerning the trifles of the wealthy, an unimportant sort of crime, intriguing and cinematic though it may be.

Fiction and movies are largely to blame. The media tends to focus each year on a half dozen filmic heists from major museums, the ones that make the headlines. Public, police, policymakers and criminals alike learn about art crime at the movies, from Thomas Crown and Cary Grant and Oceans Twelve. On the one hand, this means that just about anyone you stop on the street will find the subject of interest. On the other hand, it means that no one, not even the authorities, have been taking it too seriously: it feels like a non-threatening, victimless sort of crime, in which you can root for the bad guys because they arent really all that bad.

Its true that it is extremely rare for violence and art crime to merge. Thank goodness. But it is reductive and uninformed to consider art crime victimless. There are two ways to argue. If you are an art lover, there is of course no need to argue at all. Art, as the zenith of what civilisation is capable, must be protected. If art does not draw out your sympathies, we might point to the criminological argument. Multiple sources, from the United States Department of Justice to UNESCO to Interpol, have labelled art crime as having among the highest-grossing criminal trades worldwide, with tens of thousands of reported art thefts each year some 20,000 in Italy alone. It is a significant funding source for organised crime groups of all sizes.

Despite this, it is only in the last few years, with the rise of high-profile fundamentalist terrorism in the Levant, that the world has caught up with the experts and realised that art crime is not just interesting but very serious. While the data is not complete, it is clear that illicit looting of antiquities for sale to the West is a major funding source for terrorism. The world has taken notice: beyond the sparkling glamour there lurk shadows.