William Keith Jackson - The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House

Here you can read online William Keith Jackson - The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1972, publisher: University of Toronto Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Toronto Press

- Genre:

- Year:1972

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The New Zealand upper house, the Legislative Council was abolished in 1950 in an action which represents one of the most clear-cut examples of pragmatic politics in New Zealand history. The author attempts both to explain this unusual development and to assess its consequences.

William Keith Jackson: author's other books

Who wrote The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

THE NEW ZEALAND LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL

The New Zealand Upper House, which closely resembled the Canadian Senate, was abolished in 1950 and New Zealand became the only democratic country in the world without either an upper house or a formal, written constitution. In this historical and analytical study, the author explains the abolition and assesses its consequences over the past twenty years. He throws light on the strengths and weaknesses of the bicameral principle, the parliamentary system, and in particular the consequences of abolishing an upper house.

KEITH JACKSON was born in the United Kingdom in 1928, educated at King Henry VII Grammar School, Sudbury, Suffolk, and the University of Nottingham. He took up a post as assistant lecturer in History and Political Science, University of Otago, in 1956; subsequently appointed Senior Lecturer in 1962; Junior Fellow, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London, 1963; appointed to the chair of Political Science, University of Canterbury, in 1968. Co-author of New Zealand Politics in Action with A. V. Mitchell and R. M. Chapman, co-author with John Harre of New Zealand in the Thames and Hudson New Nations and Peoples Library, editor of Fight for Life published by the New Zealand Institute of International Affairs, and contributor to numerous other books and periodicals. The author has also contributed commentaries on New Zealand politics and current events on radio and television.

A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House

W. K. Jackson

First published in North America and Great Britain by

University of Toronto Press Toronto and Buffalo

ISBN: 0-8020-1860-2 Microfiche ISBN: 0-8020-0190-4

W. K. Jackson 1972

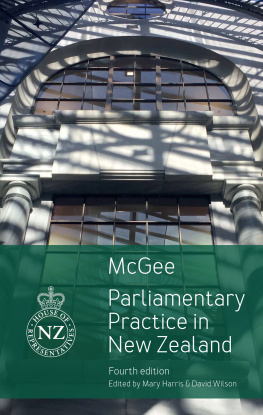

Cover illustration: Members of the

New Zealand Legislative Council pose after

the final adjournment 1 December 1950.

On 18 August 1950 the Clerk of the Legislative Council of New Zealand formally presented the Legislative Council Abolition Bill 1950 at the bar of the House of Representatives, without amendment. The bill, having passed both houses, was forwarded to the Governor-General for his assent. Three years short of its centenary the New Zealand Legislative Council ceased to be. New Zealanders had assigned the upper house to a growing pile of constitutional debris. The 82 clauses of the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 were now whittled down to 19 (many of which are machinery clauses). The elaborate provisions for Provincial Councils and Superintendents had been swept away as early as 1876, Governors had for all practical purposes lost their power by the turn of the century, and from 1 January 1951 the General Assembly of New Zealand was to be reduced to an 80-member single chamber.

New Zealand thus established a precedentpossibly a fashion in the Commonwealthby abolishing the upper house of the General Assembly. There had, of course, been several earlier examples of unicameral governments in the British Empire, although these had usually been part of federal or quasi-federal arrangements. The original provinces of New Zealand had had single-chamber legislatures; the Canadian province of British Columbia never had a second chamber, whilst in all the other provinces with the exception of Quebec they have been abolished. In contrast, only Queensland amongst the Australian states has followed the Canadian example. Elsewhere, in non-federal contexts, there have been several instances of the abolition of upper houses, but almost invariably these have proved to be of but temporary duration, such as the abolition of the House of Lords during the Cromwellian period, or the Eirean Seanad in 1936. New Zealand, therefore, would appear to be the first of the old sovereign dominions to shed its upper house with apparently permanent intent and its example has since been followed by a number of the newer Commonwealth states, the latest to consider the change being Ceylon.

Why New Zealand? For all its past reputation in the sphere of social welfare, New Zealand quite properly had never enjoyed a reputation for constitutional innovation. Moreover, more often than not experiments with unicameralism in the past have been associated with periods of revolutionary upheaval or reconstruction, as, for example, in France in 1790 and 1850, Greece in 1860, Turkey in 1923, or, more recently, Denmark and Egypt in 1953. Thus it has not been unusual for the abolition of upper houses to be preceded either by revolution or at least a referendum. In contrast, the abolition of the New Zealand Legislative Council was doubly unusual, for not only was it abolished by an ordinary act of Parliament without any preceding upheaval or test of public opinion but it was abolished by a conservativenot an innovatinggovernment. Perhaps even more surprising, and altogether unlike most other countries that have disposed of their upper chambers, no elaborate overhaul of the nations constitutional machinery was scheduled to follow abolition. The government of the day simply promised to inquire into the possibilities of replacing the old upper house, but apart from that only minor technical changes resulted. No decision was taken at the time about the wisdom or otherwise of New Zealand becoming a unicameral state, and no decision has been taken since. Denmark in 1953 replaced its old upper house with an enlarged lower house, a new written constitution, an Ombudsman, and numerous other provisions. In contrast, New Zealand did not even use the occasion of abolition as an opportunity for a reassessment of the working of its machinery of government.

This almost careless lack of interest in constitutional machinery which characterized the abolition of the Legislative Council also typified much of its nearly century-long existence. The Legislative Council clearly failed as a second chamber; there can be no doubt of that, for this is one aspect of its record on which all are agreed. The problem was to discover why it failed and when failure became obvious.

There had always been reservations about the nature of the upper house and it may be that any form of second chamber would eventually have failed in this essentially egalitarian system. The problem of whether there should be a second chamber and, if so, what form it should take is a longstanding one in many countries, and few non-federal states have resolved it successfully. If it has been customary to stress the value of a second opinion in government, rather less emphasis has been placed upon just whose opinion this should be, so that, although second chambers successfully survived the transition from privileged to democratic society, their position in newer states and more advanced democratic societies has never been easy. In New Zealand, in particular, there has always been a large gap between what might be termed the theory of bicameralism and the practice as exemplified by the Legislative Council. Political institutions are mainly modelled upon example and influenced by tradition; they are rarely constructed according to specific needs of government or considerations of efficiency. Hence bicameralism has always been an article of faith buttressed by selected examples or refuted by equally partial arguments. It certainly is not what is so often assumed, a proven system of democratic government applicable to widely different circumstances or places. The establishment of bicameral institutions throughout the old British Empire was the result not of any developed body of theory but of usagein particular, the belief that an essentially a-typical second chamber, the House of Lords, represented a basic element in a stable constitution. From British experience with the House of Lords it followed, or was thought to follow, that a second chamber would dissociate itself from the rough and tumble of party politics (whether by emasculation or forebearance was never made clear). The resulting chamber of political neuters would then somehow represent the nation as a whole against the sum of its parts in the lower house. Such a system might have had some logical basis in a federation, or before the formation of disciplined political parties, but the latter event has almost wholly undermined its rationale in the twentieth century. Beyond this, it was assumed that the upper house would revise legislation unhurriedly and sensibly and that the lower house would then accept such amendments on their merits. Even if second chambers had measured up to such assumptions they would of course reveal a fundamental distrust of the everyday process of democracy, together with a belief in the possibility of a constitutional father-figure (significantly, upper houses often consist of elder statesmen)both essentially unacceptable propositions to a New Zealand electorate. More important are the practical problems involved in setting up such a house. It is true that when the House of Lords was concerned to defend its members interests it did so with zest, but how often do such interests coincide with the nations best interests? Indeed, who is to decide what are the nations best interests at any given time? Even if it is gratuitously assumed that the House of Lords does frequently represent the United Kingdoms best interests, non-federal British colonies might have very great difficulty in finding interests in any way comparable with those of a House of Lords, even a House made up predominantly of life peers! Upper houses in former colonies often lack any effective social base capable of withstanding the democratic aura of the lower house to which governments are responsible. Indeed, events in the United Kingdom suggest that even the House of Lords, for all its centuries of prestige and tradition behind it, depends very much upon sufferance.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House»

Look at similar books to The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The New Zealand Legislative Council: A Study of the Establishment, Failure and Abolition of an Upper House and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.