Introduction

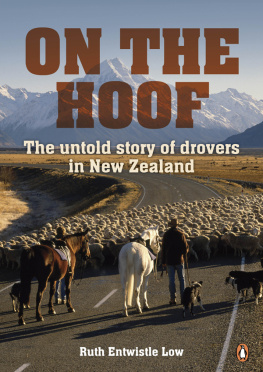

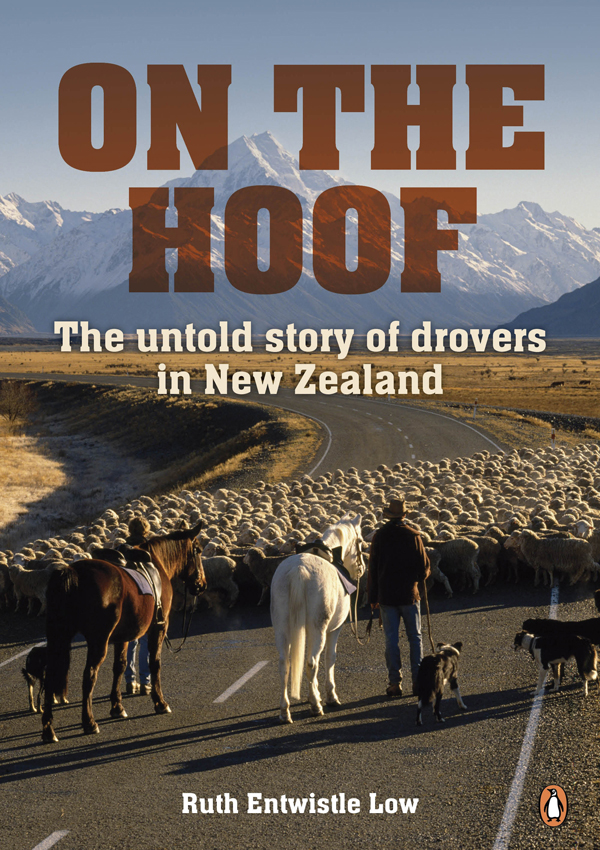

A drover, clothed in wool shirt, sleeves rolled up, tweed pants, heavy workboots, hat pulled down over his eyes to break the glare of the sun, fingers working on a rollie, reins from his mount loosely draped over a tanned forearm, ambles leisurely along the road. His horse follows docilely behind. A mob of sheep walks peaceably in front, nibbling at roadside grass as working dogs allow. An occasional shrill whistle or coarse verbal command redirects the dogs attention.

Such a scene albeit not always so idyllic has been played out in New Zealands farming history thousands of times. The romanticised image of man, dog and stock will be indelibly etched in the minds of many who have happened across such a sight while travelling in rural New Zealand. For some, perhaps, a less pleasant memory lingers of a mle, their vehicle engulfed in milling ruminants and the associated smells and noise, augmented by the verbal abuse from an irate drover. Idyllic or otherwise, such scenes are quickly becoming a distant memory as the role of the drover disappears from the rural landscape.

Droving the movement of stock on the hoof from farmgate to saleyards, abattoirs, railheads, freezing works or another farm is distinct from mustering. This history is not concerned with the many stockmen who worked the large stations with the regular mustering of livestock for weaning, shearing, marking and so on. The broader term stockman embraces both roles, and many would have carried out both tasks, but the focus of this book is on the story of stock on the road and those who drove them.

Much has been made in farming history of the role of the shepherd or stockman working in isolation and facing hardship on stations throughout the country. The drover, on the other hand, is often barely mentioned. Yet their role was an important one when you consider the number of stock that were sold at saleyards annually a number that increased exponentially from the time of settlement, and grew as the impact of the development of refrigerated transport took hold and freezing works sprang up around the country. Even with the advent of rail and, later, trucking, droving was still the main means of stock transportation well into the twentieth century.

This books aims to redress that imbalance and to acknowledge the work of those men, women and children who drove thousands of head of valuable stock along the roads of our small nation. They were a significant cog in the huge agricultural mechanism that generated so much of our countrys wealth. For the drovers there was no sense of anything extraordinary in what they were doing, yet for many there was a real love for their work. Despite the hardships sleeping rough, meagre rations, cold and miserable weather, the run-ins with inconsiderate motorists, the loss of stock or dogs if the opportunity arose to drove again, many would jump at it.

This book aims to introduce the reader to the drovers from those who drove the very first sheep in to the pastoral runs to those who are the last of a dying breed and to record the individuals on the road, their work, their tools of trade, the territory they covered and the challenges they faced. It also looks at the reasons for droving in the context of the emerging farming environment, and of drovings twilight years. Much of the material for this book is based on some 60 interviews with those involved in the droving industry. The interviews provide a colourful insight into what has become an almost forgotten field.

Within the drovers ranks were the educated, and the uneducated, those who chose to go droving and those who fell into it. There were shepherds, stockmen and the odd rogue or two. Women, too, feature in the history of droving: the long-suffering pioneer women who journeyed out with their men and a few head of stock to make a go of their allotted acres; the land girls in World War Two, manpowered onto farms, many with no farming experience at all; and the girls who gave up aspirations of a career to stay and work on family farms, who drove stock to railheads or saleyards as part of their farm duties. In the 1970s a few women could be found out in front of mobs of cattle, driving a truck towing a caravan. There were also those who might have only been droving a few times and who would not classify themselves as a drover at all, but the memories of those experiences would always awaken a spark in them. The experiences offered a freedom from the routine of everyday life, an element of adventure with the rough and ready lifestyle, the unpredictability of working with stock, and perhaps a bit of romanticism not that they would readily admit to that.