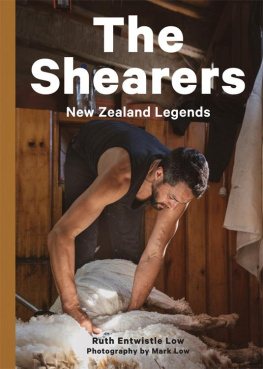

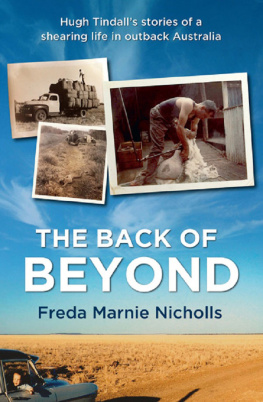

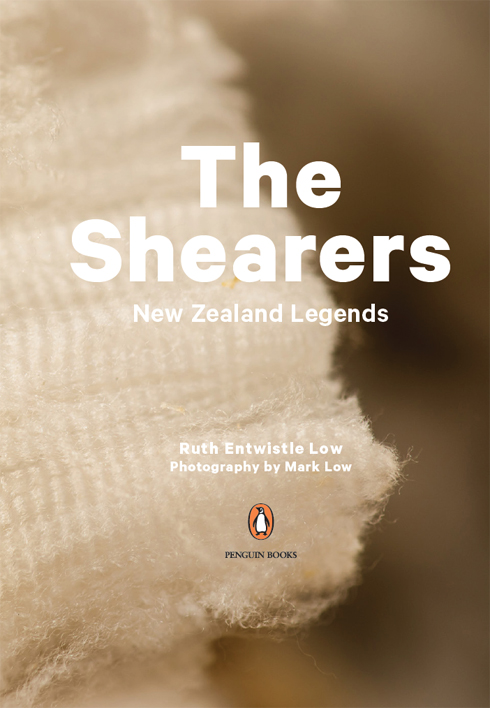

Their voices in their own words, often brutally honest reflections on what it is to be a shearer are at the heart of this book: their training, their tools, their camaraderie, and the gruelling, itinerant nature of the job.

Old hands like Brian Snow Quinn, Tony Dobbs and Peter Casserly, and Peter and Elsie Lyon, as well as those newer to the scene, offer personal insights, often for the first time.

To Stewy, my writing companion and more importantly, my dad.

Shearers work in some of the most remote, beautiful country in New Zealand. Quail Flat woolshed, Muzzle Station.

Introduction

Driving up to any one of the myriad woolsheds around the country at shearing time, youll invariably find a host of vehicles parked outside: the owners ute, with all manner of farming paraphernalia on its flatdeck; the contractors ute, maybe with the tailgate open revealing a spare grinder waiting to be brought into the shed if needed; and, of course, the ubiquitous Toyota HiAce or Ford Transit vans with the contractors details splashed across the sides. Emerging from your vehicle you instantly become aware of activity. If the big sliding door of the shed is closed, you hear a low but incessant thrum; if the door is ajar the sound is more assaulting: loud music merges with the drone of shearing machines. There may also be the sound of cloven-hoofed ovines running over wooden gratings while harried from holding pen to catching pen, ready for shearing. Adding to the intensity of sound and action is their bleating and the occasional sharp bark from a working dog.

Care is called for as you walk up muddy steps to the landing of the shed; chicken wire nailed tightly over each step warns of the potential to slip. Then, standing at the entrance to the shed, you look in, immediately feeling like a rank outsider as you take stock of all that is unfolding. Depending on the size of the shed there could be anything from a handful of people to the equivalent of a rugby team plus subs working inside. They are all in a constant state of motion, but you sense they know that foreigners are watching. You are met with equal parts curiosity and suspicion. It is very easy for an urbanite to feel intimidated.

How does one absorb and make sense of it all? You are slow to enter for fear of upsetting the carefully choreographed routine. There is no mistaking the shearers on the board their handpieces moving snakelike across the sheeps skin, the machine power-cord pulled at the beginning and end of each decloaking (the frequency of the action denoting the shearers experience level). But as to the other cohort, it takes time to understand the pattern of their movement. There are those sweeping wool away from shearers with paddle-like brooms, and those coming to pick up each fleece and throw it on a central table where others gather round, grabbing rapidly at the fleece and removing anything detracting from its quality. One of those around the table folds up the fleece and passes it on to a circular revolving table where someone, looking official, examines each fleece and makes a decision as to what bin, of which there are several, it will be placed into. Theres a person who comes over, takes great armfuls of wool out of a bin and loads it into a press, where it is eventually compressed into a bale. Somewhere close by, a pile of wool bales is building up, marking the number of sheep that have already passed over the board. All the time the machines and music batter your ears, and theres the odd bit of chatter and laughter. In the corner of the shed the cocky and contractor may be chatting, but their eyes sweep the scene, keenly observing the team in motion. Somehow all these individuals work in unison to ensure that the cockys sheep are shorn and the wool processed as quickly and with as little fuss as possible.

When brave enough to enter you shake hands with the cocky and they talk to you about their sheep, their breed and what they are aiming to produce. There are the fine wool growers, ensuring the fleeces of their merinos are treated with considerable respect, as the fleece is a valuable commodity. Then there are the cross-breds, which produce coarse wool; the farmers eye then is perhaps not quite so sharply attentive on the wool. In todays market coarse wool generates little income, its value having gradually declined to a point where, for many, shearing has become about maintaining animal health rather than seeing a substantial wool cheque augment their income. Fortunately for them the lamb market is buoyant, so, with an eye to meat, they talk of changing farming practices to optimise profit.

Next, you catch up with the contractor, who explains the roles of those in the shed. Of course, the shearers need no explanation; but there is conversation around who are the best in the team. The fastest shearer or, in old parlance, the ringer is in the middle stand, close to the table to ensure the wool flows easily to the woolhandlers. With another sheep down the porthole he straightens, clicks his tally counter, wipes his brow on the towel hanging on a string across the frame of the pen door and swings the catching door open; selecting his next target, he grabs it firmly under its chin, tips it up and drags it out, positioning it nicely, the animal relaxed. Then the shearer picks up his handpiece, pulls the cord and starts down the animals brisket or chest. The movement is smooth and controlled, the sweat beading on his brow the clear evidence of exertion.

Your head turns to someone at the last stand and you begin to realise that perhaps it is not as easy as it looks. A young shearer struggles to position his ewe correctly and it is kicking out. The contractor slips over to give him a hand, signalling to move his foot around into the sheep more. Once positioned properly, the contractor pulls the cord for the struggler and stands patiently watching, offering words of encouragement and further advice when needed. Once the sheep is down the porthole the contractor grabs a ewe out of the pen, takes the handpiece, pulls the cord and starts to peel the wool off; the struggler seizes the opportunity to stretch his back, then stands by, taking in every move, studying the placement of his bosss feet.

Once the lesson is over the contractor is back beside you explaining the ins and outs of the woolhandlers, pressers and classers jobs. Woolhandling terms fly out at a rate of knots fribs, dags, crutching, skirting, VM (vegetable matter), lines, cotty Meanwhile, you watch each fleece being gathered, walked to the table and unfurled with a fluid throw; there is a moment to see if it settles perfectly on the table or lies draping over the edge. Again, you are aware that the expert hands make it look easy. Its a mesmerising spectacle.

There is the occasional cry of sheepo, the universal call for the presser or young lad out in the pens to fill the shearers catching pen. The shearer is down to their last sheep and nothing must interrupt their flow. The pen is quickly filled, with lifting of gates, shoving of sheep and bleating all part of the equation. And as you take the time to watch and glean, the necessity for teamwork becomes evident. One member of a shearing gang cannot function without the other: each has a distinct and necessary role to play. But your eyes cant help but be drawn back in admiration to the shearer. As they click their counter, wipe their face and launch in to grab yet another sheep, you wonder what it is that drives them.