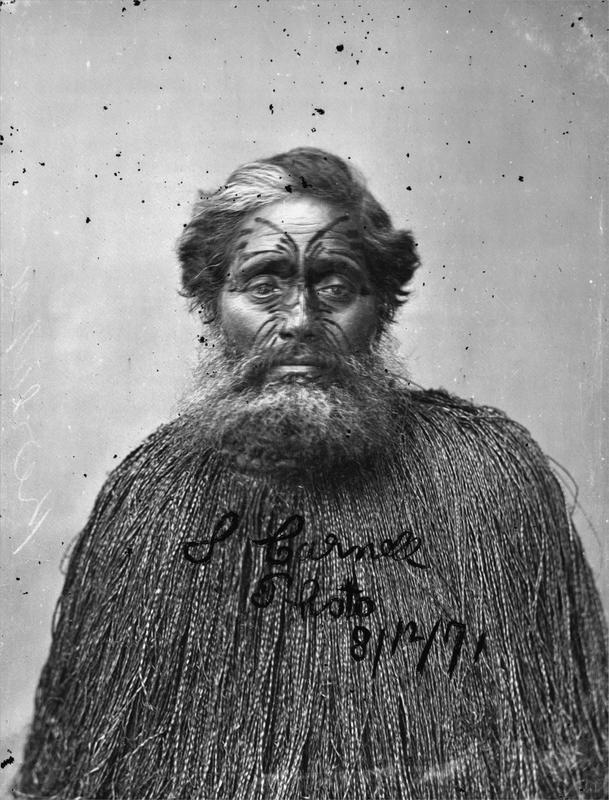

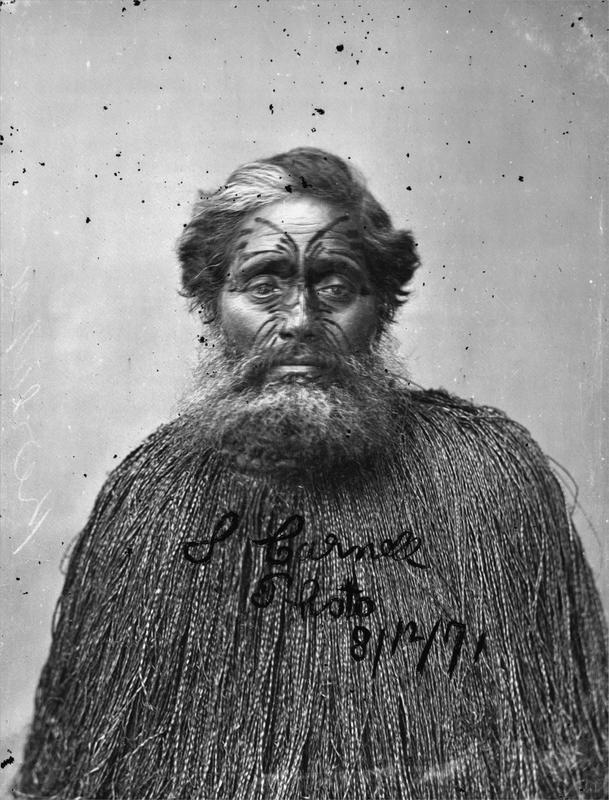

Kereopa Te Rau, photographed by Samuel Carnell, 8 December 1871, inside Napier Prison, just a month before his hanging. This is the second of only two photographs that exist.

This is the story of a photograph.

In late November 1871, Kereopa Te Rau was brought to Napier to stand trial for the murder of an Anglican minister called Carl Sylvius Vlkner. The murder happened at Opotiki. A trial was held in late December. The jury retired and 10 minutes later returned with a verdict: Kereopa was guilty.

Everything went into suspension over Christmas and New Year. On Friday, 5 January 1872, at 8 oclock in the morning, Kereopa Te Rau was hanged in the yard of the Napier Prison. A small crowd witnessed the scene. His body was taken away and buried in secret. At his burial was a 36-year-old French nun: Sister Mary Joseph Aubert.

Who was the man in the photograph?

Kereopa Te Rau was known as the infamous Eye-Eater of the Rev Vlkner. He had been on the run for almost seven years. In some ways he was the most notorious person in New Zealand. There was a bounty placed on his head, and he was hunted down by kupapa Maori. He was ambushed in the Ureweras, marched over to Wairoa. There he was put on a boat to Napier, guarded closely.

The photo was taken by Samuel Carnell, photographer of choice for leading Heretaunga Maori in Napier. The photo is dated 8 December 1871. In the photo Kereopa Te Rau is wearing a piupiu raised high up to his neck. After his capture, Kereopa Te Rau had slashed at his throat with a razor. The cloak was used to cover the wounds. A photographers hand has clumsily touched up the surface of the photograph by adding moko. This was probably an attempt to make Kereopa Te Rau look more savage, like a cannibal, a curiosity. Instead he looks sad, as if staring inwards, or back at the voyage that had brought him to that point, facing the glassy lens of a camera recording his capture.

This book, in a way, is all about the moment of that photograph. This is not a book about the justice or injustice of the hanging or the political events that led to his trial. Rather it is a voyage around the subject, an attempt to understand what led to the moment the camera clicked. This contrapuntal method of working came from my last book, The Hungry Heart Journeys with William Colenso. In that I learnt to go where the story sent me: Sometimes its the winding roads, the missed turns or the unplanned surprises that make a simple journey something special, as an advertisement for travel puts it.

Colenso connects with this new book, and in fact he led me to this story. He wrote and published a passionately argued defence of Kereopa Te Rau called Fiat Justitia. In this he argued, essentially, to look at things from the other side. This was a remarkable act of courage at a time of heated feelings, in a small and isolated town. Colenso made the same voyage as Mary Joseph Aubert, walking up to Napier Prison, situated high on the seaward side of Napier Hill. He wanted to console the human who was facing death as a convicted murderer. He empathised with his outsider status.

Another person duelling for Kereopas soul was Bishop William Williams, a man who had hurriedly left the East Cape, like a thief according to a contemporary Catholic priest. This was after Kereopa Te Rau came to his mission station, carrying the head of Rev Vlkner. Williams had retreated to Napier. He had a visceral loathing of Colenso because of the damage Colenso had done to the Anglican Church with the birth of Colensos illegitimate Maori son, Wiremu. He also felt ambivalent about Kereopa Te Rau since he had, in effect, ejected Williams from his Turanga (Gisborne) mission.

Both Colenso and Williams attended Kereopa Te Rau at different times as did Mary Joseph Aubert, who spent part of his last night in his cell, offering solace and prayer. She defined him as the good thief.

All this happened over a strange part of the year: Christmas to New Year, a traditional time for shabby things to be hidden. (Today it is when pay rises for parliamentarians and judges are slipped through.) Christmas is interesting, with its pragmatic use of an ancient pagan festival for a mythical birth of a Christian saviour. New Year also brings celebration, and anticipation of change (or more of the same). Both times are vacuums in which time slows down.

Perhaps it was an attempt to enter the same strange listlessness of this time of year that first sent me on a visit to Napiers old colonial prison. My modus as a writer is to go to places and pitch the historical past against all the vagaries of the present. Something about the way the present treats the past, either ignoring it or celebrating it or even telling false stories about it, interests me. It was New Year 2012. I was still exhausted from my last book, but I felt this incurable curiosity about this site in Napier that I had never visited. (Why visit a prison, after all? They are sad places, a capturing of souls.) But as I made my way up the winding path to Napiers colonial prison, I realised I had already begun a new voyage. I was at the start of a journey towards understanding a complex and, in this case, highly controversial part of Aotearoa New Zealands past.

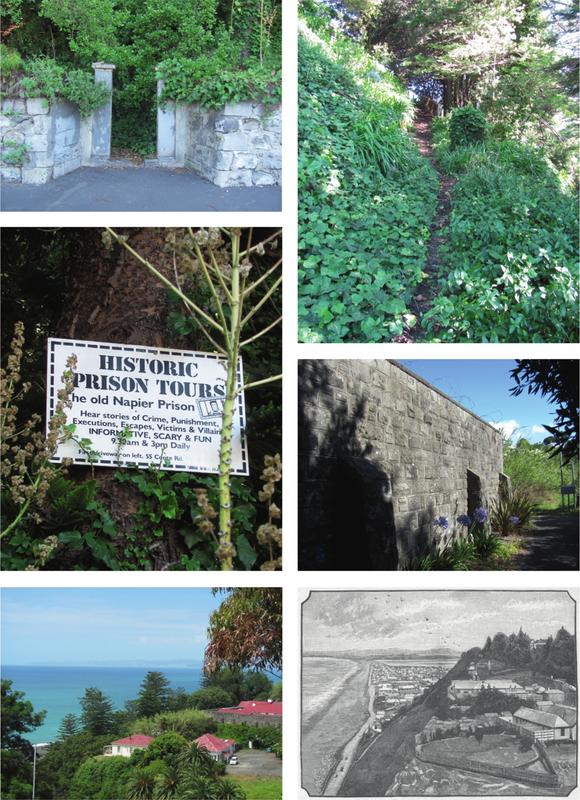

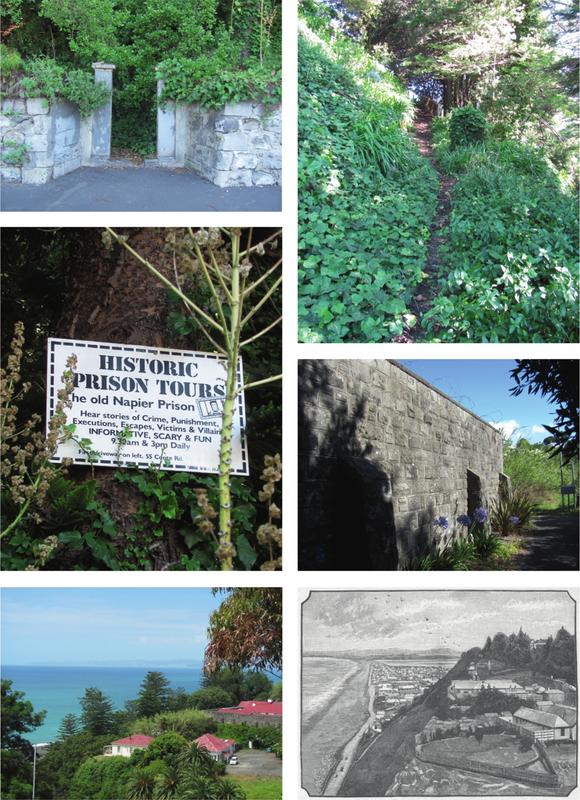

The path led me up to some elegant stone walls. Time had softened the harsh lineaments of the prison: weeds and flowers were growing, and the prison had become a tourist site. I had seen vans running around town advertising prison visits. Online I had read about scary night tours with the hint of ghosts and rattling chains. I wondered privately how much of the past could be retained in these circumstances.

I blundered my way around with my iPhone, unsure what was old what had been there when Kereopa was brought to the prison. I was trying to get a feel for the layout of the buildings, which were complex with seemingly endless add-ons. Today the prison doubles as a hostel, so it was not unusual to come across a sleepy backpacker emerging from a cell, walking down the hall with toothbrush in hand. But there was something insistent within the architecture.

Napiers colonial prison is both a museum and backpackers. It runs Informative, scary and fun tours daily.

Its inner darkness leached out. I felt my own spirits lowering, then my breath became shallow as I experienced the oppression of the small, dark cells. Something curious happened as I walked down a corridor: a door had been left open and a noise reached my ears. It was the sound of the sea. (Napier Hill itself is like a cupped hand at an ear, catching echoes of waves.)

It turned out I was not alone in noting the sound of the waves, especially when the surf is running high. Colenso had written an essay on just this occurrence. He called this low continuous semi-metallic sounding the calling of the sea. It turned out Mark Twain had also noticed it when he stayed at the Masonic Hotel opposite Napiers shore in 1895. It was a sound bred among the ice fields of Antarctica [it has] a note of melancholy in it proper to the vast unvisited solitudes it has come from. It is very delicious and solacing to wake in the night and find it still pulsing. This sound became an accompaniment as I set out on my journey to write this book.