Sometimes its the winding roads, the missed turns or the unplanned surprises that make a simple journey something special.

I have travelled a good deal in New Zealand, but I never knew of a worse piece of low country to get through.

1.

Even today it seems to be in the middle of nowhere. You drive along, away from Napier, leaving the regular pacing of the Norfolk pines behind. Suddenly youre in a strange tangential space, a kind of no-mans land. You sense youve reached the limit of urbanity. After all, were in regional New Zealand here. Its the east coast of the North Island, a relatively isolated place.

On one side, the sea limitless. If you could see round the curve of the globe there would be nothing till you got to Chile. On the other side, a railway line, weeds. A few buildings crop up, the kind of light industrial buildings fated to be empty. Theres something faintly criminal about them or is this the aura of abandoned real estate? Theres a sign: fresh paua for sale.

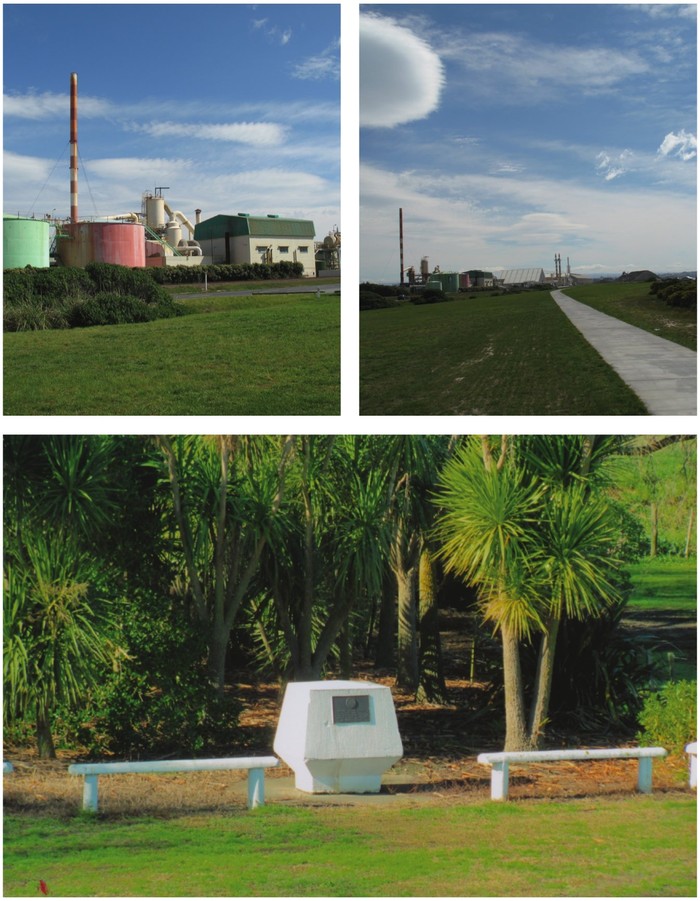

Further along is something alarming. Its a huge industrial complex, the sort you situate as far out of town as you can. Theres a tall narrow chimney belching smoke. Its the Ravensdown fertiliser works. The entire building is covered in a light grey scum of powder. This is a long way from the tidy prettiness of Napiers art deco quarter.

And not far from here, over a bridge and on the seaward side of the road, you come to the place Im looking for. Down off the busy road an arterial highway is a kind of paddock. If youre not careful you will have driven past before you even glimpse it. And when you glance there, what you see mystifies rather than intrigues. Only too soon youre on another bridge, crossing another river. But lets reverse. Go back in time too.

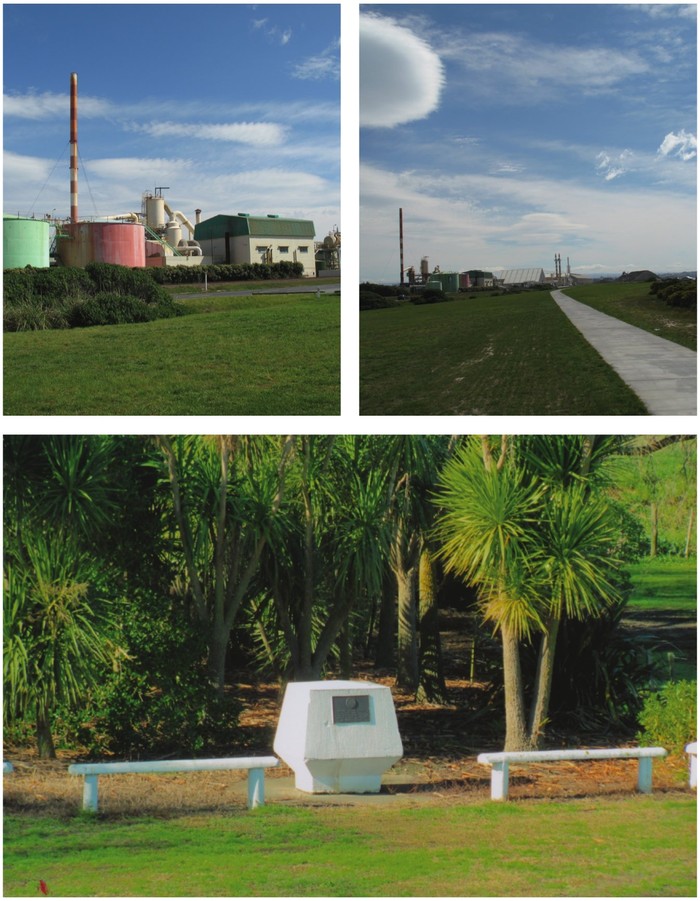

Theres a strange-looking concrete monument protected by a white fence. From the road, its difficult to see what it is. Theres a large sign saying Waitangi, the name only making the situation more perplexing. Isnt that the name of the most significant site in New Zealand? Where the Treaty was signed? What has the heavily symbolic Treaty to do with this strange rootless space?

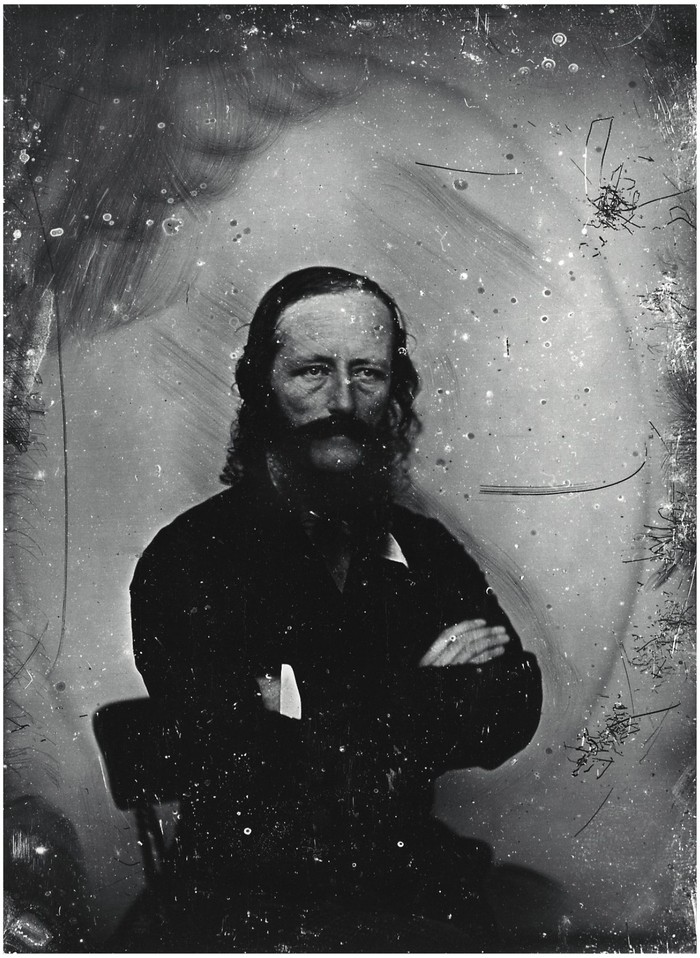

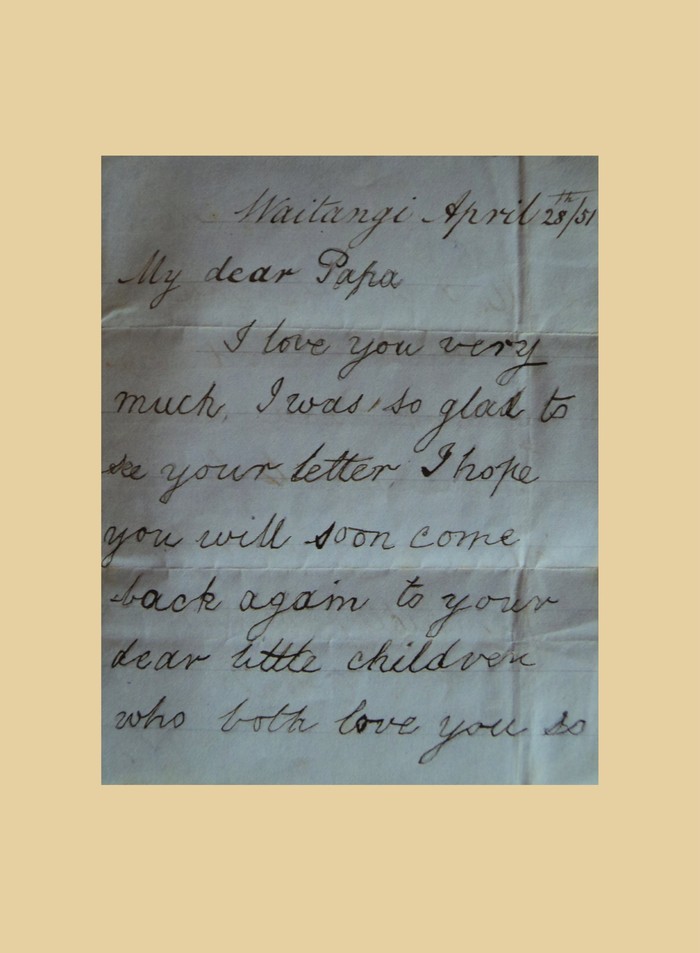

Ever since I began my research into the life of William Colenso Ive been obsessed with this place. This is the site, ostensibly, of Colensos mission station. The mission lasted here from December 1844, when William, his wife Elizabeth and their daughter Fanny arrived in Hawkes Bay, till 8 January 1853, when the mission house burnt down. By then William Colenso had been expelled from the church. His two children had been taken away from him and his wife was soon to walk out of his life, never to see him again.

This, then, is the site of a tragedy, or at the very least a disaster. But it also marks the site of a collection of buildings. One of these was the beautiful library Colenso created, a building of such beauty that all who saw it Bishop George Augustus Selwyn and Native Land Purchase Commissioner Donald McLean, for example recognised it as something special. In fact it was hardly ever called a library. Its preferred name, whare tuhituhi, is a clue to its complex bicultural origins. This was early in New Zealands history the Treaty had been in existence, after all, a slim four years when Colenso came to Hawkes Bay. He was a Cornishman with an eye for ravishing beauty. Within weeks of arriving he made it a priority that he have his own manspace. It had a raupo shell, its interior lined with tukutuku panels in the palest black and white delicately picked out with red. Here he arranged his bookcases, which went to the ceiling.

On these shelves he had the great works of Romanticism, which shaped his soul as much as religious texts like Wesleys Sermons. There were also the more practical books like Universal Science, which would guide him on how to build a chimney, fumigate letters infected with the Plague, print calico or how to use locusts as food. Because a missionary living in such an isolated place had to perform daily a series of what amounted to small miracles. He also had to be everything: minister, doctor, administrator, builder, farmer, gardener, diplomat husband, father, lover.

In this room, surrounded by a density of European knowledge, Colenso corresponded with botanists William and Joseph Hooker at Kew Gardens in England, sending them samples that helped map the plant life of New Zealand. And in this room he probably consummated one day, quickly, casually after a long period of looking at one another his relationship with Ripeka Meretene, a young Maori woman he had known since she was a girl. So it is more than likely that in this room Wiremu, his beloved illegitimate son, was conceived.

In his darkest days, after he was ejected from the Church Missionary Society (C.M.S.), William Colenso clung to this piece of ground. Even after the mission house was burnt to the ground in highly suspicious circumstances, he stayed on, living in the whare tuhituhi. He simply refused to shift. Let the place of my disgrace be the place of my exile, he said. It was a long seven years before he was forced to move on.

Theres a lot of living here, a lot of passion and its opposite: emptiness. It is this that draws me to the site, again and again.

The Waitangi mission went under many different names. Even in its own time, Bishop William Williams, missionary William Colensos immediate superior, called it Te Awetoto, Waitangi and Ahuriri. Maori letters sent to Colenso varied the address from Ki a te Koreneho, Te Awapuni to Ki a te Koreneho, a Waitangi.

But this name vanished. The site took on a new identity when the ship that brought the Treaty of Waitangi to Hawkes Bay anchored off the Tukituki River in June 1840. The river became known as Waitangi. However, when Colenso put an ad in the local newspaper offering a 30 reward for information on the evil-disposed person or persons who broke into his storeroom on 23 December 1861, destroying Glass, Books, Writings, Natural History Specimens, Medicines, &c &c, the closest he could pinpoint it, geographically, was near the Ferry, Waipureku (or Clive as we now call it).