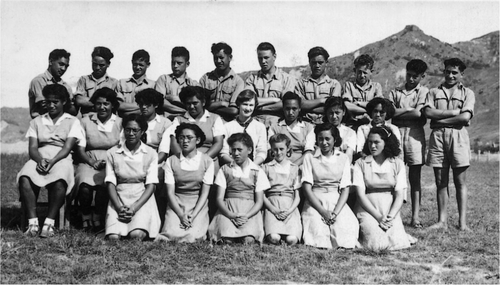

My thanks go to all those who have helped me put this book together. My special thanks go to my schoolmates at Tokomaru Bay Maori District High School, whose photo is below.

In the more than 160 years since the Treaty was signed at Waitangi on 6 February 1840, it has had a chequered history. Against a background of enormous social and political change, it was ignored and relegated to the status of a quaint historical document by one group of signatories; while the other signatories and their descendants tried in vain to remind the others of the promises and values the Treaty contained. While Pakeha New Zealand did its best to ignore the Treaty, Maori New Zealand kept it always in sight.

In the latter part of the twentieth century a number of factors drove all New Zealanders to take another look at their founding document, to consider more seriously the claims of those who said they had been cheated, who were insisting that the Treaty be validated, be made part of the law of the land so that its promises could be realised.

Since then we have been arguing extensively, publishing endlessly, demonstrating occasionally. The debates have waxed and waned; everyone has an opinion that everyone else should be listening to. New issues have engulfed us in part because a bigger population and higher expectations have put more pressure on our natural resources. In the 1980s one of the issues was who had the right to fish and where; at other times it was how we should handle Waitangi Day celebrations and what they really meant. In 2003 and 2004 the issue keeping us awake at night has been who could or should own parts of the seabed and foreshore.

The emphasis has moved from the actual words of the Treaty itself to the underlying principles. We inherited democracy from the Greeks but modified it to include a wider range of people. The American Constitution, too, had to be amended to include the large proportion of its population who were slaves and women. In the same way, it is unrealistic to expect a document rattled up in a hurry nearly 170 years ago to fit neatly into the 21st century. The process of defining and realising the principles will be a long one especially as we realise the system of government and law inherited from Britain may not be an exact fit for a Pacific nation in the 21st century. We are beginning to realise that the Treaty will be an important part of our future as well as of our past and present.

Many of us grew up in a time when the Treaty was just a dusty parchment on the classroom wall. Some have disliked the uncertainty; have longed for it all to be over, finished, forgotten so we can get on with our lives, as they say. I am not one of them. I think that taking the Treaty, or in other words the MaoriPakeha relationship, out of the closet where it was stuck for many a long year, giving it a jolly good shake, dusting it off and deciding where we go from here, was a very healthy thing for a society to do. To debate the issues, to decide what the Treaty really means today, to disagree and work out positive compromises is a characteristic of a democratic, forward-looking nation. I am proud to participate in the process.

My own background has been similar to that of many New Zealanders. I lived in rural areas, side by side with Maori communities , went to schools of predominantly Maori pupils, usually in a classroom with a portrait of Lieutenant Te Moananui- a-Kiwa Ngarimu, the first Maori awarded the Victoria Cross, on the wall behind me. Not until I studied history, taught history, wrote about New Zealands past, did I feel I had a better understanding of the society I had grown up in.

This book is my chance to contribute to the debate. Much has been written about the Treaty already, but often by specialists in law, history, politics or race relations. I have tried to present the key information directly and simply, in order to make the main issues accessible. My hope is that you, the reader, can build on this framework to decide for yourself how we should move in the future.

Marcia Stenson

The Treaty itself

There are two texts. They are not a direct translation of each other. This is the text signed by 43 northern chiefs at Waitangi on 6 February 1840:

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Ko Wikitoria te Kuini o Ingarani i tana mahara atawai ki nga Rangatira me nga Hapu o Nu Tirani i tana hiahia hoki kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga me to ratou wenua, a kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki kua wakaaro ia he mea tika kia tukua mai tetahi Rangatira hei kai wakarite ki nga Tangata maori o Nu Tirani kia wakaaetia e nga Rangatira maori te Kawanatanga o te Kuini ki nga wahikatoa o te wenua nei me nga motu na te mea hoki he tokomaha ke nga tangata o tonu Iwi Kua noho ki tenei wenua, a e haere mai nei.

Na ko te Kuini e hiahia ana kia wakaritea te Kawanatanga kia kaua ai nga kino e puta mai ki te tangata maori ki te Pakeha e noho ture kore ana.

Na kua pai te Kuini kia tukua a hau a Wiremu Hopihona he Kapitana i te Roiara Nawi hei Kawana mo nga wahi katoa o Nu Tirani e tukua aianei amua atu ki te Kuini, e mea atu ana ia ki nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani me era Rangatira atu enei ture ka korerotia nei.

Ko te tuatahi

Ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uru ki taua wakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu te Kawanatanga katoa o o ratou wenua.

Ko te tuarua

Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite ka wakaae ki nga Rangatira ki nga hapu ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou Taonga katoa. Otiia ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa atu ka tuku ki te Kuini te hokonga o era wahi wenua e pai ai te tangata nona te wenua ki te ritenga o te utu e wakaritea ai e ratou ko te kai hoko e meatia nei e te Kuini hei kai hoko mona.

Ko te tuatoru

Hei wakaritenga mai hoki tenei mo te wakaaetanga ki te Kawanatanga o te Kuini Ka tiakina e te Kuini o Ingarani nga tangata maori katoa o Nu Tirani ka tukua ki a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi ki ana mea ki nga tangata o Ingarani.