Copyright 2013 Aime Craft

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review, or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from ACCESS (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency) in Toronto. All inquiries and orders regarding this publication should be addressed to:

Purich Publishing Ltd.

Box 23032, Market Mall Post Office, Saskatoon, SK, Canada, S7J 5H3

Phone: (306) 373-5311 Fax: (306) 373-5315 Email:

www.purichpublishing.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Craft, Aime, 1980

breathing life into the Stone Fort Treaty : an Anishinabe understanding of Treaty One / Aime Craft.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-895830-64-4

eISBN: 978-1-895830-66-8

1. Canada. Treaties, etc. 1871 Aug. 3. 2. Ojibwa Indians Manitoba Treaties. 3. Ojibwa Indians Legal status, laws, etc. Manitoba. 4. Ojibwa Indians Canada Government relations. I. Title.

KE7749.O45C73 2013 346.7104320899733307127 C2012-908315-1

KF5662.O45C73 2013

Edited, designed, and typeset by Donald Ward.

Cover painting: Bi-go-ima nemi She Dances Anywhere, by Linus Woods.

Cover design by Jamie Olson.

Index by Ursula Acton.

Purich Publishing gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, and the Creative Industry Growth and Sustainability Program made possible through funding provided to the Saskatchewan Arts Board by the Government of Saskatchewan through the Ministry of Parks, Culture, and Sport for its publishing program.

Printed on 100 per cent post-consumer, recycled, ancient-forest-friendly paper.

Acknowledgments

After almost a decade of working in Canadian Aboriginal law, I took the opportunity to follow another path and to explore Treaty One from an Indigenous legal perspective. This book is a revision of my thesis prepared in the context of a Law and Society Graduate program at the University of Victoria. I am grateful for all the guidance and mentorship that was offered, from my supervisory committee; Jeremy Webber and Michael Asch, professors; John Borrows, Judy Fudge, Michael MGonigle, Jean Friesen, Heidi Stark, and Taiaiake Alfred, my readers and editors; Kerry Sloan and Jeanette Gevikoglu, and Megan Menzies. I am also grateful to the University of Victoria, the Law Foundation of British Columbia, Legal Aid Manitoba, and Indigenous Peoples and Governance (IPG) for their support. My Elders Ron, Greg, Aldeen, Dave, Gerald, Joe, Peter, and Sherry reminded me throughout the process that we are all connected. They kept me centred, focused and helped me grow as a person, as a thinker and in my own spirit. It was an amazing experience. What I have to show for it is because of them, but, of course, the mistakes are my own.

Miigwech to my family, my friends, my relatives in Victoria, in Manitoba and all over Turtle Island you have inspired me.

Miigwech to my Mom and Dad. You give so much and ask for so little.

Miigwech to my mishomis. You taught me all that I needed to know to be Anishinabe, a good person. You showed me that love and kindness really have no limits.

Miigwech to my ancestors. May you know that I carry your thoughts for us in my little heart.

Miigwech Kije-Manitou.

Dedication

For all of those who have gone on, those who are here today, and in particular, to those who are yet to come. May you honour the treaty relationship.

Authors Note: The Anishinabe (Ojibway, Chipewa, Ojibwe or Anishinaabe) language, anishinabemowin, has many dialects. In some areas, Anishinabe people will refer to the plural form as Anishinabek or Anishinabeg. Some will also use a double vowel, e.g. Anishinaabeg, to refer to the long sound of that vowel.

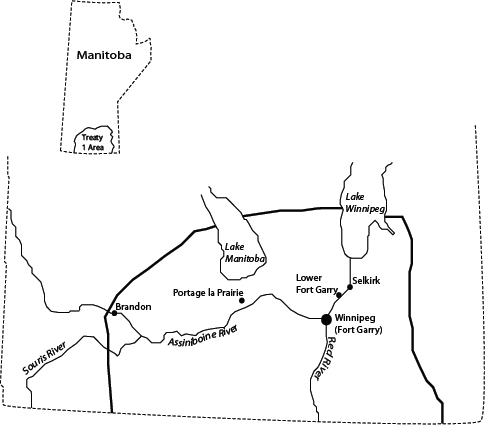

Lower Fort Garry (the Stone Fort) was built in 1830 by the Hudsons Bay Company on the western bank of the Red River, 20 miles north of the original Fort Garry, which is now in Winnipeg. Treaty 1 was signed there.

Foreword

I first met Aime when she travelled to the west coast to further her understanding of Indigenous law. As an accomplished lawyer, she brought a rich knowledge of the role of Canadian law in structuring foundational relationships. Her expertise in issues related to Indigenous land rights, resources, consultation, human rights, and governance was readily apparent to everyone she met. What distinguished Aime, however, was a special attentiveness to the constructive role which language and tradition can play in legal affairs. Thus, when she came to Vancouver Island, she immediately sought out Elders and other Indigenous knowledge keepers to learn more about the development and transmission of law within this context. As a result, she quickly deepened her insights about the role of traditional law in Salish life, and this redoubled her determination to research and write about the laws and teachings of her Anishinaabe Elders living in Manitoba, Ontario, and beyond. The book you now hold in your hands is the culmination of this work. Aimes careful research and clear writing presents a vision of law which places treaties and Indigenous traditions at the heart of Canadas law.

When First Nations peoples made treaties with the Crown, they deployed powers of reason, persuasion, and judgement. Their active participation made a difference to the process by which treaties were negotiated and the terms they eventually contained. In taking a significant role in their development, First Nations inevitably weighed and balanced their perceptions of the Crowns views and, in light of the information available, they made decisions about the Crowns words and deeds. This is all to say that First Nations had their own ideas about what treaties meant for their way of life and their future. In fact, many influences would have informed First Nations evaluations of these matters. Indigenous perceptions of economics, sociology, politics, spirituality, and the power of personality would have all played an important part in deciding how to analyze the governments words. Intermixed with these forces was the role of Indigenous law. Though differently expressed across diverse societies, law sets standards for judgement which assist communities in considering how to receive and deal with peoples and nations from other lands. Thus, it should come as no surprise that Indigenous law helped First Nations make judgements regarding how they should relate to people representing the British Crown. Indigenous law was not only present during the debate, deliberation, and discussion leading up to and during treaty negotiations, Indigenous law also played a significant role in the development of conditions which First Nations negotiated as part of these agreements.

This book shows the immense power of Indigenous law in the treaty-making enterprise. Using a clear and straightforward style, Aime examines the role of Anishinaabe law in the creation of Treaty One, in what is now southern Manitoba. She does a masterful job of weaving an Anishinaabe context throughout this work as she demonstrates how knowledge of Indigenous law makes a considerable difference in understanding the nature and scope of treaty agreements. While Aime would be the first to admit that any academic discussion of Anishinaabe law during Treaty Ones negotiation only reveals the tip of this iceberg, she nevertheless provides important informational keys which help to unlock basic Anishinaabe concepts vital to comprehending its meaning. This has led her to produce an exceptional work of great insight and consequence. This book holds significant potential for shifting our views about the basic nature of law in structuring, interpreting, and sustaining Crown-Indigenous relationships, not only in Treaty One lands, but throughout Canada. It is a must read for everyone interested in understanding the importance of Indigenous law in Canada.