Copyright 1998, 2012, 2015 by William Loizeaux

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or arcade@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

Visit the authors website at www.williamloizeaux.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62872-595-7

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-618-3

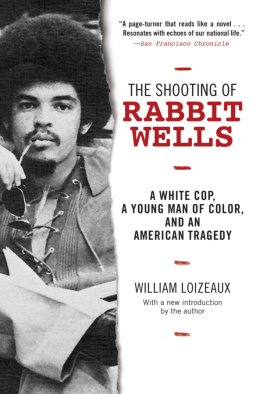

Cover design: Owen Corrigan

Cover photo courtesy of Bernards Township Public Library

Printed in the United States of America

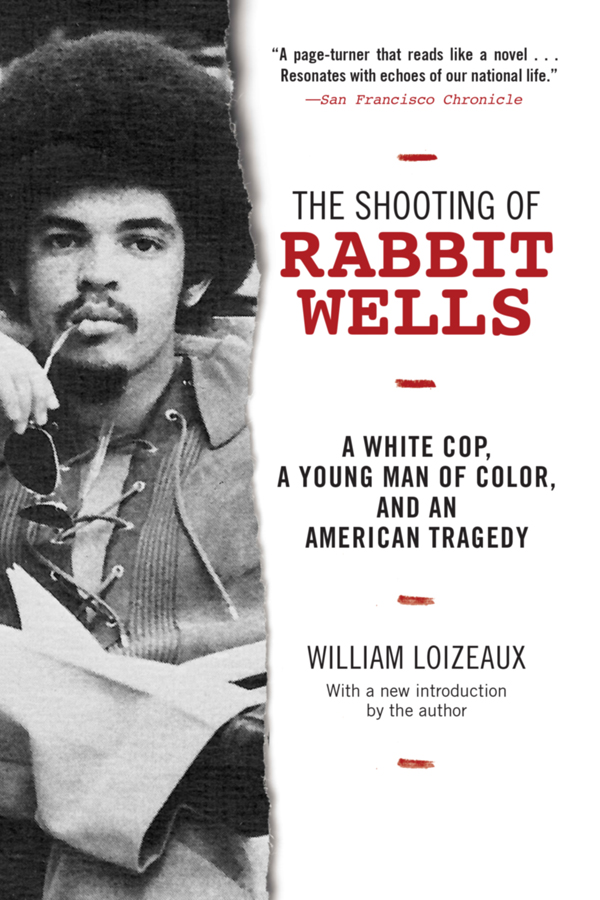

A LSO BY W ILLIAM L OIZEAUX

Anna: A Daughters Life

The Tumble Inn, a novel

For Young Readers:

Wings

Clarence Cochran, a Human Boy

For Beth and Emma

Contents

Introduction to the 2015 Edition

Im writing these words about five months after the videotaped choke hold death of Eric Garner by police in Staten Island, New York, about four and a half months after the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and just weeks after grand juries decided not to indict the policemen involved in those homicides. Im also writing one day after the revenge shootings of officers Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos in Brooklyn, New York. And who knows how many other such events will happen between now and when you are reading this some months in the future.

All these killings appall and sicken us, and to be honest, my first impulse has been to turn away from them, as I turn away from much that is ugly, bewildering, painful, and dispiritingespecially when it reopens a wound that Id like to think is slowly scarring over. That wound, of course, is our history of racial prejudice and violence, which, for me, erupted into consciousness in the early 1970s, when there were widely publicized shootings of police and killings by police of men of color, including a young man, William Rabbit Wells, with whom I went to high school.

In many regards, the life and death of Rabbit Wells were different from those of Michael Brown and Eric Garner. Though born in urban poverty, Rabbit spent the last seven years of his life in the virtually all-white, upper-middle-class New Jersey suburb where I grew up. As a ward of the state, he went to one of the best public schools in the county. By and large, he was well-liked by his white classmates. When he died at twenty-one, he was three years older than Michael Brown and twenty-two years younger than Eric Garner at the times of their deaths. Before he died, hed had no run-ins with police, even for minor offences.

Yet across the span of forty years, there are glaring similarities among these cases, as if in many places the distrustful dynamics at the intersection of race and policing have remained essentially and tragically the same. Rabbit, like Brown and Garner, was a physically impressive dark-skinned man. In a moment of intense confusion in the doorway of a local bar, a policeman believed he was lethally dangerous and aggressiveand shot himwhile in fact Rabbit, like Garner, had just helped break up a fight. And there are eerie similarities, as well, between the military-style tactics and training that we saw in Ferguson and the training and experience of the young white officer, William Sorgie, who killed Rabbit. Sorgie was a good and dedicated policeman, a decent man by all accounts, and a decorated Vietnam veteran. Just a few years before he shot Rabbit, he had been taught to save his and his fellow soldiers lives by shooting at whatever moved in the jungle. Little of his subsequent police training contradicted those methods and honed instincts. As with the Ferguson and Staten Island killings, a grand jury determined not to bring the case to trial.

In The Shooting of Rabbit Wells, first published in 1998, twenty-five years after the event itself, I finally came to grapple with what had happened to my classmate. This book, a memoir, is my effort to find out as much as I could about Rabbit and Sorgieand not just about the historical context and immediate circumstances of the shooting, but about the complicated, imperfect, and altogether human lives that each of them brought to that moment. I wanted to know: Who were each of these people?

To answer that question, I gathered as many facts as I could. I interviewed Sorgie and his colleagues many times over a number of years. I interviewed many of Rabbits friends, read his poetry, visited the places where hed lived, and scoured my own memories of him. What I was really trying to do, I realized, was to walk in the shoes of these young men, to imagine their situations, their thoughts and feelings, especially those of Rabbit.

I am aware that such imagining is problematic. Much criticism has been aimed at memoirs such as this. Imagination and memory, which is inevitably shaped by imagination, are uncertainly related to objective fact. That is true enough. The problem of memoir, however, is not the problem of memory or imagination but the problem of writers who present them as fact. In telling the story of Rabbit Wells, I tried to guide readers through different kinds of evidence and levels of certainty, and to inform them of what is fact, what is memory, and what is imagination.

Then there is the issue of imaginative overreach. Who was Ia man who had never been to war, never been a policeman, never put my life on the lineto think that I could imaginatively share Sorgies perspective? And most importantly, who was Iamong other things, a middle-aged, middle-class white manto think that I could imaginatively share Rabbits perspective, his radical difference, his otherness? Indeed there are those who believe that to try to do so is condescending, an act of appropriating an other, thereby erasing the others subjective experience and even reinforcing existing patterns of privilege.

I do not deny this as a possibility. But nor do I think it a certainty. For there is another, more constructive possibility: that imagination and the empathy it enables, going both ways across racial lines, can lead to some deeper understanding of our similarities and differences and to a greater awareness of injustice and the workings of privilege. Imagining our way into someone elses life through writing or reading can change us and reshape our attitudes and actions. We should be aware of and guard against claiming too much for the power of imagination: imagination, empathy, and the understandings that come from them are always approximate at best. But that should only urge us to exercise those faculties as fully, self-consciously, and honestly as we can.

As a result of my efforts, as awkward and approximate as they might have been, I think I came to know Rabbit betterhis vulnerability, his aspirations, his regrets, his anger, his fear, his strutting cockiness, his loneliness, his burning need to be loved. In other words, I came to know something of his inner world, that it was rich and intricate, and that while that world was uniquely his, we also shared some passions and hopes, the fulfillment of which was affected by our different circumstances, among them, importantly, race.