First published 1996 by M.E. Sharpe

Published 2015 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1996 Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use of operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, William Wells, 18151884.

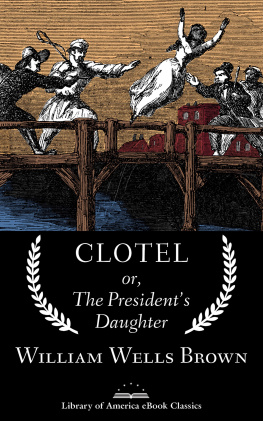

Clotel; or, The presidents daughter : a narrative of slave life in the United States / William Wells Brown : a new edition with primary documents and an introduction by Joan E. Cashin.

p. cm. (American history through literature)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-56324-803-4 (alk. paper). ISBN 1-56324-804-2 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Children of presidentsSouthern StatesFiction.

2. Jefferson, Thomas, 17431826Relations with womenFiction.

3. Afro-American familiesSouthern StatesFiction.

4. Afro-American womenSouthern StatesFiction. 5. Women slavesSouthern StatesFiction. I. Cashin, Joan E.

II. Title.III. Series.

PS1139.B9C531996

813.4dc2096-762

CIP

ISBN 13: 9781563248047 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 9781563248030 (hbk)

Novelists, poets, and essayists often use history to illuminate their understanding of human interaction. At times these works also illuminate our history. They also help us better understand how people in different times and places thought about their own world. Popular novels are themselves artifacts of history.

This series is designed to bring back into print works of literaturein the broadest sense of the termthat illuminate our understanding of U.S. history. Each book is introduced by a major scholar, who places the book in a context, and also offers some guidance to reading the book as history. The editor will show us where the author of the book has been in error, as well as where the author is accurate. Each reprinted work also includes a few documents to illustrate the historical setting of the work itself.

Books in this series will primarily fall into three categories. First, we will reprint works of historical fictionbooks that are essentially works of history in a fictional setting. Rather than simply fiction about the past, each will be first-rate history presented through the voices of fictional characters, or through fictional presentations of real characters in ways that do not distort the historical record. Second, we will reprint works of fiction, poetry, and other forms of literature that are primary sources of the era in which they were written. Finally, we will republish nonfiction such as autobiographies, reminiscences, essays, and journalistic exposs, and even works of history that also fall into the general category of literature.

Paul Finkelman

William Wells Brown published this book, the first novel by an African-American writer, in 1853. The title character is a mulatto woman, one of two illegitimate daughters of President Thomas Jefferson. Abandoned by her father, Clotel is raised in Virginia by her slave mother. As a young woman, she becomes the lover of a white man; when he too abandons her, she is sold into slavery in the Old Southwest. Later she manages to escape, but when slave-hunters close in on her, she takes her own life rather than go back to bondage. The novel was greeted with considerable acclaim, and within a decade it went through four editions. Scholars have praised the work for its realistic depiction of the daily horrors of slavery and racism, and for its frank condemnation of the slaveholding founders of a democratic republic. Other critics have admired Browns further achievements as an author, for he published many books in his long life.1

But historians have yet to explore fully the fact that this novel is about women of color. This work is the first in American literature to concentrate on slave women. William Wells Brown focuses on the experiences of Currer; her mulatto daughters with Jefferson, Clotel and Althesa; and her quadroon granddaughters, Mary, Ellen, and Jane. Their destinies occupy center stage, and the complicated, mostly unhappy fates of these six women provide the foundation for the narrative. (The concentration on women distinguishes this book from Harriet Beecher Stowes Uncle Toms Cabin, with which it is often compared.) The novel resembles other mid-nineteenth-century works in that it is populated with many other characters whose lives are intertwined through implausible, melodramatic encounters. Like other books of its time, the narrative is interleaved with poems, newspaper articles, and autobiographical asides. Yet Brown never loses his focus on women of color and their distinctive suffering under slavery. He offers some bold assertions about gender, especially regarding the nature of black, mulatto, and quadroon women, and he also makes some extraordinary observations about race relations and identity.2

The authors life yields a number of clues about how he came to be preoccupied with gender, race, and identity. Brown was the offspring of an interracial relationship, and he was so light-skinned that he was sometimes mistaken for Caucasian. Born in 1814 or 1815 on the Kentucky plantation of Dr. John Young, his mother was a slave named Elizabeth, and his father, George Higgins, was either Youngs half-brother or his cousin. So William was a blood relation of the man who owned him. His own father he scarcely knew, but Brown learned something about his other ancestors. His maternal grandfather, a mulatto slave named Simon Lee, had served with the Patriot army in Virginia during the Revolution. He also heard the rumor, probably from his mother, that his other grandfather was none other than Daniel Boone. (Even though the famous frontiersman lived in Kentucky for the last quarter of the eighteenth century, there is no evidence that Brown was his descendant.) Browns mother remained the center of his emotional life, and as a boy William could hardly bear to see her punished. As a teenager he once tried to help her escape, but they were both soon recaptured.3