Copyright

Copyright 1969 by Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brown, William Wells, 1815-1884.

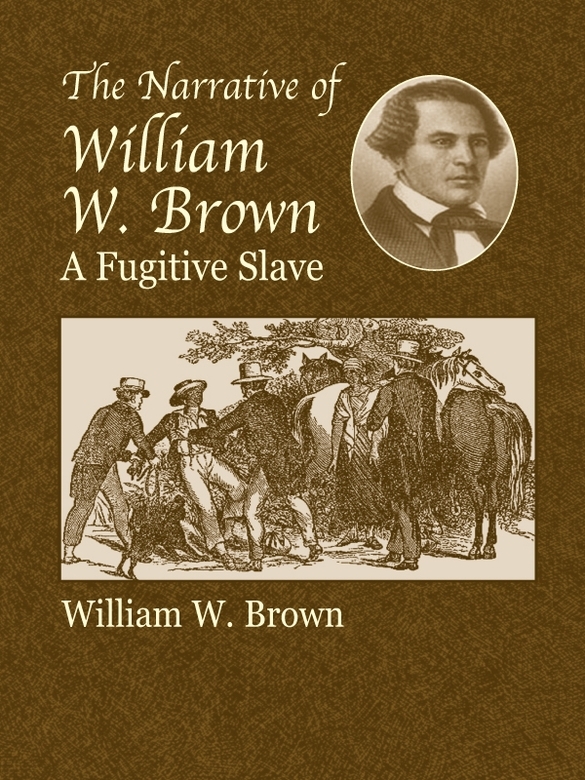

The narrative of William W Brown, a fugitive slave / William W Brown :

introduction by Larry Gara.

p. cm.

Originally published: 2nd ed. Boston : Anti-Slavery Office, 1848.

Includes bibliographical references.

9780486148663

1. Brown, William Wells, 1815-1884. 2. Fugitive slavesUnited States

Biography. 3. African AmericansBiography. 4. SlavesMissouri

Biography. 5. SlavesUnited StatesSocial conditions19th century. I. Title.

E450.B8828 2003

305.567092dc21

[B]

2003048896

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

INTRODUCTION

It is a terrible picture of slavery, commented Edmund Quincy about William Wells Browns newly written manuscript, told with great simplicity.... There is no attempt at fine writing, but only a minute account of scenes and things he saw and suffered, told with a good deal of skill, propriety and delicacy. Quincy was an abolitionist editor and the son of Harvards president. When Brown asked him to read the manuscript, he intended only to glance at a few pages, but found it so good he could not put it down until interrupted by a call to dinner. He readily agreed to write a letter to be prefixed to the book, and suggested to the author only one or two alterations and additions.

Browns narrative quickly became a best seller and took its place with the memoirs of Frederick Douglass, Moses Roper and other former slaves whose writings contributed to the growing antislavery sentiment in the northern states. Whatever their literary merits, the works of ex-slaves had the ring of authenticity. Unlike the white abolitionists, these men could not be accused of speaking without knowledge and experience of the Souths peculiar institution. A contemporary writer said of the slave narratives that they were calculated to exert a very wide influence on public opinion because they contained the victims account of the workings of this great institution.

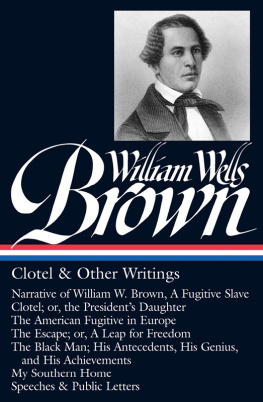

For William Wells Brown, born a slave in Kentucky around 1816, publication of his memoir brought fame and probably some monetary compensation. The first edition of a thousand hardbound and two thousand paperbound copies cost him less than eleven cents a copy, and it was quickly out of print. With its personal approach and vivid pictures of slave life, Browns narrative quickly found a receptive audience. In addition to the American versions, it was translated into several foreign languages and circulated in European editions. The book was only the first of a notable series of literary productions from Browns pen. In 1848 he published a short anthology of antislavery songs, The Anti-Slavery Harp, and in 1852 his travel book, Three Years in Europe, appeared in London and Edinburgh. The following year he published a novel, Clotel, or the Presidents Daughter, whose main character was an alleged mulatto child of Thomas Jefferson. Though it could not compete successfully with Uncle Toms Cabin, it was the first novel published by an American Negro, and as such was a significant work. Brown wrote several dramas about slave life and published one in 1848: The Escape; or, a Leap for Freedom. In The Black Man, His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements Brown traced Negro history back to its African origins and included short biographical sketches of notable colored persons. Other writings included The Negro in the Rebellion, and several historical volumes expanding on the material first presented in The Black Man. The number of his publications is impressive and contemporary critics were nearly unanimous in praising their quality.

It is the second, or 1848, edition of Browns memoir which is reprinted in this volume. He made very few changes from the first edition, but he added several appendices and this new edition contains as well a transcript of a speech he made in November, 1847 to the Female Anti-Slavery Society of Salem, Massachusetts. The narrative was written thirteen years after Browns escape from slavery and reflects, therefore, both the conditioning of his long contact with abolitionists and the vagaries of detail implicit in writing from distant memory. Nevertheless, it is full of insights about slavery and the ante bellum South which only a former slave could know. Furthermore it is important both because of the impact it had on thousands of readers and because of the wealth of material it contains.

Even before publishing his narrative William Wells Brown was known as an effective antislavery speaker, one of a number of former slaves whose message reached many northerners untouched by the white abolitionist crusader.

Unlike Frederick Douglass, his more famous contemporary, Brown never broke with William Lloyd Garrison and the moral suasion school of abolitionists, though their reactions to him and his contribution varied considerably. It is a long time since I have seen a man, white or black, that I have cottoned to so much as Brown, on so short an acquaintance, said Edmund Quincy. Brown, he said, was an extraordinary fellow, with no meanness, littleness, no envy or suspiciousness about him. On the other hand some of the abolitionists were suspicious of the former slaves motives. Samuel May, Jr., when he learned of Browns impending trip to England, noted that he was a very good fellow, of very fair abilities and has been quite true to the cause. But he likes to make popular and taking speeches, and keeps a careful eye upon his own benefit. Brown owed everything to the Garrisonian cause, said May, and he ought to be true to it. As it turned out, Brown consistently defended the Garrisonians during his stay in England.

Still the Garrisonians were concerned that certain of Browns actions would hurt the cause. When his marriage seemed in danger, they urged reconciliation with his wife.

Despite the misgivings of his antislavery friends, William Wells Brown suffered no loss of manhood or of courage as a result of his manumission. Indeed, it gave him a new sense of security which freed him to continue his labors for antislavery and other reform causes. For in addition to abolition, Brown actively supported the peace crusade and the temperance movement. It was partly to participate in an International Peace Congress in Paris that he first traveled to Europe in 1849. He spoke at the meeting but found little support for his introducing antislavery matters into the proceedings, and left the Congress disillusioned with its results.

For William Wells Brown, however, the plight of Americas colored people, whether slaves or nominally free, was always uppermost. The unique contribution of the fugitive slave speakers was to personalize slavery and remove its operations from the realm of abstract ideas. But for Brown and the others the battle against slavery was only half the warthe other was the battle against prejudice and discrimination in the North as well as in the South. In his books and in the letters he wrote to newspapers Brown called attention to the indignities suffered by colored people in the free states. A letter from England recalled the discrimination he had encountered on steamers, in hotels, in coaches, railways, and even in churches where he was forced to sit in a Negro pew. When he arrived in Britain, he said, for the first time in his life he felt truly free.