Table of Contents

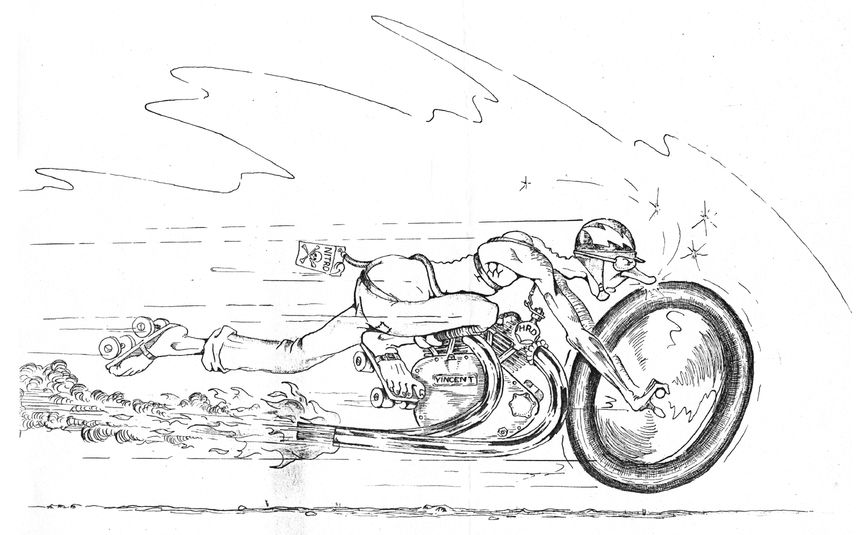

Inspired by Sid Bibermans Vincent, a young artist made this sketch during a drag meet back in the late 1950s. Ever since, this logo has served as the calling card of Big Sid, a master mechanic whose work has earned him the love and respect of motorcyclists the world over.

FOR LUCY

Who insists that this book be called:

Big Sids Vincati: The Story of a Grandfather, a Father,

and the Daughter of a Lifetime

Oh, we all like motorcycles to some degree

Bob Dylan

Fuelie heads and a Hurst on the floor

Shes waiting down in the parking lot

Outside the 7-11 store

Bruce Springsteen

Said Red Molly to James thats a fine motorbike

Richard Thompson

Prologue: In the Hospital

I sit with my father in the emergency room while the doctors tell him what he has already guessedhe has had a heart attack. The admitting physician says that the extent of the damage is still unknown, and we will need to see a specialist. After they do the paperwork to transfer him from the ER to cardiac, Im asked if I have a preference for a heart man.

I dont know any doctors in Louisville. I say, Its in Gods hands. The physician nods and assigns my dad, Sid, to the next available surgeon in the rotation. I am told that he will have his bypass surgery the next morning.

Alone at home that night, I cant help but feel weighted down by guilt. For the past twenty years, my father has barely been a part of my life. I fall asleep, fully expecting him to die.

But the next morning, five hours after they wheel him away, the surgeon tells me Sid is now in stable condition and should regain consciousness. He may be unconscious for a while, though, and I can go home until they call me. Still I ask to see him.

While listening to the wheeze of the ventilator, I reach down and squeeze Sids hand. His unconscious, immobile body lies there draped in a sea green gown that is woefully inadequate in size. When I was tying it up in the ER, I examined the vast expanse of his back, slashed and pockmarked from past surgeries. The soft flesh was a mottle of different shades of brown, each splotch the result of some crash or accident. Sleeping, he looks at peace and grandly indifferent to the world. His last look at me before they rolled him away had been far different: terror mixed with acceptance.

Now I watch his eyes calmly move under his lids, and the sight calms me. His feet hang off the bed. He needs a haircut. His salt-and-pepper crown of hair stands up crazily. As I linger, the smell of industrial antiseptic solvents mixed with sweat grows stronger. After squeezing Sids hand once more, I leave.

Time passes. Back at school, my lectures on Shakespeare roll out of my mouth in a robotic monotone. I forget to hang my parking card, and the campus police tow my car. I tell no one the reason for my distraction. And then the call comes: Sid is awake and off the ventilator.

Soon after, I sit beside him again and the first thing he says is, Why didnt they just let me die?

I know he means it, and for the first time, I realize why he didnt call me after suffering his heart attack. When I climbed those stairs that day and let myself into his ramshackle apartment, I found him waiting to die. The previous night we had watched a movie. I had promised that I would stop by in the morning, but instead slept in. Not wanting to apologize (after all, I was no kid and in no mood to be kept on a short leash), I hadnt called. Instead I had simply pulled up unannounced and hours late, expecting to take him to lunch. It was a beautiful Sunday afternoon in September. I opened the door and saw him, sunk in his one good chair, grasping a pillow, pressing it tight to his chest.

There wasnt time to think as I raced him to the ER. But now there was. What to say? How do you comfort a man disappointed at still being alive? Thats when I began to put it all together. A few months earlier, when Sid moved from Norfolk, Virginia, to Louisville, it had not been to start a new life but to end, on his own terms, the only life God gives you.

As we talk, his eyes transfix me: endless black pools. It looks like he wants to sink into the bed to be covered over in the soft earth. Youd never know that the man lying there was a legend, one of the best motorcycle tuners in the country, if not the world. From all over, riders came with their bikes in tow. I would wake to find strange men, often from foreign lands who spoke little English, wanting to know if this house was where Big Sid lived. Sometimes they wanted to stay and just watch my father fix motorcycles, but Sid never liked to work with the spotlight on him. Like any good magician, he had earned the right to his own secrets.

When Sid was young, riding his red Vincent Rapide, he liked to play a game with guys who thought they were fast on their motorcycles. He would pull alongside, bolt upright, catching his prey. The other rider was feeling full of himself, the spark of life shining in his eyes as he hugged the tank of his Harley, or Triumph. And then suddenly there sat Big Sid, six feet five, three hundred pounds, as comfortable as can be on top of his Vincent. Sid would lean over and yell, Have ya got it all on? Then the game would commence, and it had only one ending: Sid would shift into fourth gear, wind it out, and vanish up the road. Sometimes as he pulled away hed glance over to see their expression: that same shattered face I saw there in the hospital.

When Sid has his heart attack, I am three years into my job as an English professor. I had thought I was on a secure career path, but now, with little to show for it in the way of publications, I am facing the very real possibility that soon I might not be granted tenure. And no tenure means no job. My wife, Martha, and I are also trying to start a family, and she has just told me she thinks she might be pregnant. Suddenly, the prospect of taking care of her, plus two other family membersone old, one newstrikes me, there in that hospital room, as almost too unbearable to contemplate.

My mother had predicted it all. With Sid in Louisville, she said, I was about to get engulfed in my fathers physical collapse: the knees were going; the back was shot; and, of course, the heart. The looming financial burden reminds me why I had been so adamant about running away from Sids world. Someone once said that motorcycles are the best way to take a large fortune and turn it into a small one. In my fathers case, his youthful joyriding had given way to the endless grind of running a motorcycle shop. The fame he had inadvertently accrued was of the purest sort, coming always with honor and never with money; his old racing wins were nothing but talk and a collection of half-broken trophies, most stashed in boxes in the attic. The comedian Jay Leno put it well when he told me that in a perfect world guys like my dad would be the ones living in the big houses. No surprise, then, that from age eighteen on I was terrified that Id end up like Sid: broke and at the mercy of life.

And Sid knows what I feared. In his bed, he looks up at me almost as if to say, Its okay to say good-bye, son. With no clue what to do, I mouth back empty words neither of us believe. Then I tell him to get some sleep and I slip out of the room. Convinced I need to do better next time I visit, I drive over to his apartment and rummage around, looking for pictures and magazines, anything that might help him find the will to live.