To my childhood family that provided a foundation of love and faith, and to my adult family that has allowed me to build on that foundation.

Contents

Foreword by Bert Blyleven

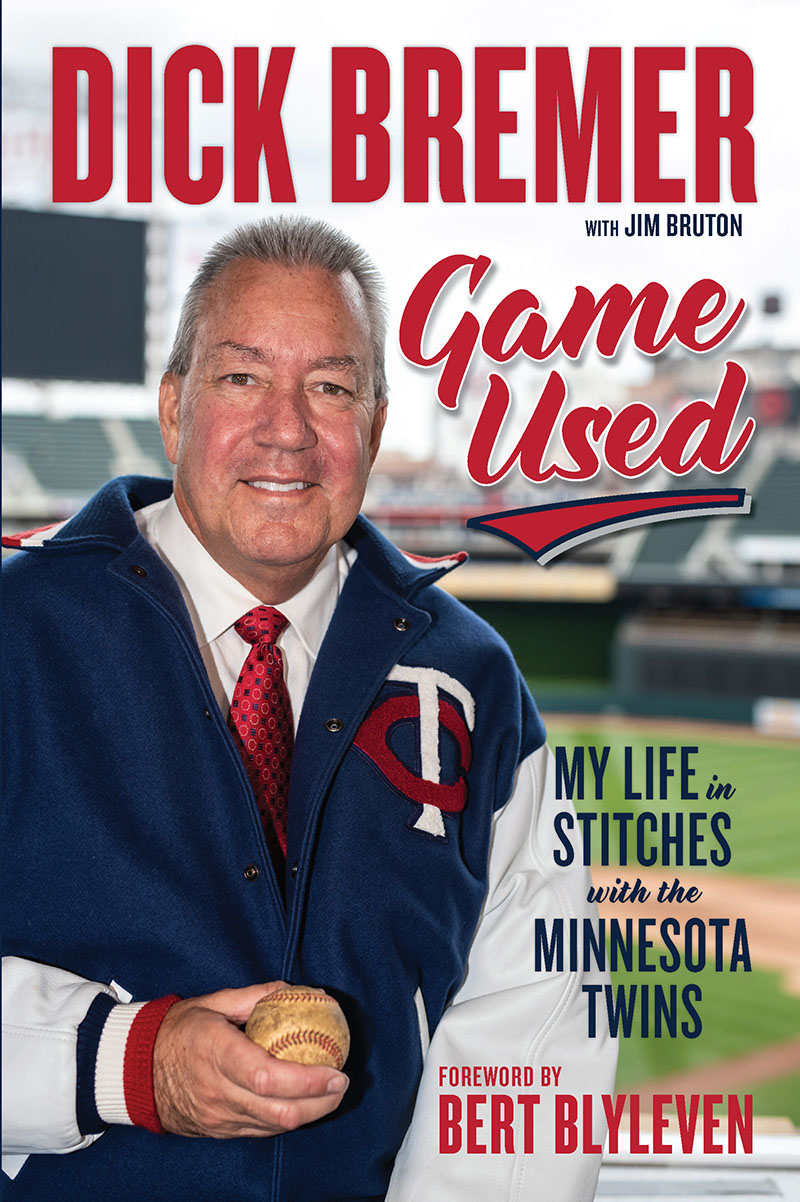

When I was asked to write the foreword for Dick Bremers book, I was honored. I have known Dick since 1985, when I was traded back to the Twins from the Cleveland Indians, and in 1995 I began broadcasting with him, as an analyst, covering Twins baseball.

Thinking about the best way to describe our relationship over the years, I always think about the TV series The Odd Couple . Dick is Felix and I am definitely Oscar.

Dick is a true professional when it comes to his job as the play-by-play announcer and I have enjoyed being his analyst over the past 25 seasons. His memory, knowledge, and passion for Twins history goes back to his childhood. You will read about his love for Twins baseball throughout this book.

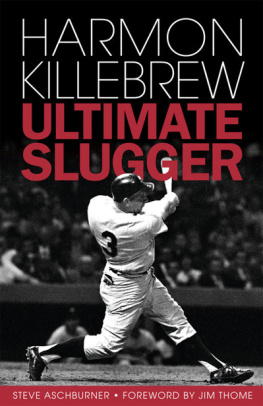

The Twins have had the honor of having many great TV and radio announcers since the franchise came to Minnesota in 1961. Men like Ray Scott, Halsey Hall, Herb Carneal, Ralph Jon Fritz, Bob Kurtz, Ted Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, Frank Quilici, Jim Kaat, John Gordon, and now Cory Provus and my former teammate Dan Gladden. The Twins have been very fortunate to have had Dick Bremer in the booth over the past 37 seasons.

I have always believed that sports announcers are teachers of the game, whichever game or event they broadcast. Growing up in Southern California I actually learned my curveball while listening to Dodgers Hall of Famer Vin Scully and Jerry Doggett describe Sandy Koufaxs curveball on the radio. They would describe the curveball as being dropped off a table.

Baseball is a great game full of memories and characters. This book will bring back so many Twins memories and exciting moments in Twins history.

After a Twins win, Dick would tweet that he is having a left-handed toast, meaning the Twins put a win in the left side of the won-lost column. I think you will give Dick a left-handed toast after reading this book!

Bert Blyleven spent 22 seasons pitching in the major leagues, 11 of them with the Minnesota Twins. He is currently a color commentator for the team alongside Dick Bremer. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.

Introduction

Like most people who enjoy the game of baseball, I think a new baseball is a thing of beauty. Its a joy to look at and to hold, and Ill confess that, on more than one occasion, Ive held a new ball up to my nose to smell it. A new baseball has so much hope, promise, and mystery. Will it be hit for a home run? Will it land on the chalk-line just beyond first base on its way to the right-field corner? Will it be fouled off to be caught by an adult who hands it off to a child, brightening the face of a seven-year old whos watching a big league game for the first time?

For me, a used baseball is infinitely more beautiful. Look at the baseball on the cover of this book. Its been beaten into the ground countless times; rolled through the mud; been hit, caught, and thrown by dozens of men, women, or children. Yet it still remains round, though discolored and scuffed, having brought joy to everyone who has touched it.

If were lucky, our lives over time become like a used baseball, bearing no resemblance to what they once were. Ive been very lucky. The game I fell in love with in my childhood has become a big part of my adulthood. Along the way, there have been some bad hops and errors. What follows is an anecdotal look108 stories, one for every stitch on a baseballat a blessed life that has allowed me to passionately broadcast games for the team that I followed as a child.

Externally, weather, use, and time have taken their toll. Internally, the core has never changed. The joy and excitement I felt watching my first baseball game is still there. Through six decades, Ive seen thousands of home runs and great catches and witnessed many incredible moments, each one intensifying my passion for this incredible game. Its been a fun ride. I hope you agree.

First Inning

Stitch 1. Sainthood

Like a lot of great baseball players, such as Paul Molitor, Dave Winfield, Jack Morris, and Joe Mauer, I was born in St. Paul, Minnesota. For that matter, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Charles Schulz were also from St. Paul and might have been better baseball players than I was. I couldnt play baseball like those four St. Paul All-Stars, but I did develop the same love of the game.

Shortly after I was born, I was adopted by Clarence and Eleanora Bremer through the Lutheran Friends Society in St. Paul. My father was a Lutheran pastor specializing in deaf ministry. He was assigned the Minnesota region and traveled all over the state from Rochester to Grand Rapids preaching in sign language. After having to give up deaf ministry due to health reasons, the church reassigned him to a very small town called Dumont. Picture the shape of the state of Minnesota; Dumont is nearly in the middle of the bump in the western part of the state. The population back then was 235; its less than half of that now. It was there that I was introduced to the great game of baseball.

The Dumont Saints played, literally, in my backyard. Ralph-Leslie Field sat behind the hedge that bordered our property. It was like a lot of town team fields at the time. The scoreboard was above the outfield fence in left-center field. It was manned by a boy who sat on the ledge in front of the scoreboard, paying attention regardless of how hot or cold it was, and hanging the appropriate numbers up after each half inning. They do the same thing, roughly, at Fenway Park, but with a lot more romance. The dugouts were too small to stand in and the bench sat about eight inches off the ground. Every other Wednesday night and every other Sunday afternoon the Saints played their home games 100 feet from my back door. They played in the Land O Ducks League, which included teams from Graceville, Chokio, Beardsley, and just about every other small town and hamlet in the region.

Im not sure how it was possible, but it seemed that even though there were only 235 people living in town, twice that many people attended the baseball games. The outfield fence consisted of a snow fence taken down at the end of each season. A creek ran behind the left- and center-field fence. Behind the right-field fence, cars and trucks parked door handle to door handle. Whenever the Saints scored a run or made a great play in the field, the fans in their vehicles honked their horns.

There was never any formal advertising for the home games. On game days, a sandwich board was placed in the middle of Main Street that read, Baseball Today. Thats all it took. Most people didnt drive to the ballfield, except for those parked behind the right-field fence. One of the benefits of being in a town that small is you could be on the outskirts of town and be no more than a five-minute walk to the baseball field. Once at the field, it seemed that the Lutherans gravitated toward the third-base line. The Catholics went to the first-base side. This was, after all, the late 50s.

A Dumont Saints game was the social event of the week, where the number of spectators was larger than the number of people who lived in town.

A bonus for us kids was the bounty placed on foul balls. A ball fouled over the backstop, the road down the right-field line, or the hedge down the left-field line was worth 10 cents upon its return to the home dugout. That resulted in some of the nastiest eye-gouging, arm-twisting, and finger-pulling fights this side of All-Star Wrestling. It was Darwinism in its purest form; the fastest and strongest kids got most of the reward money. The ultimate goal was to get three foul balls and collect your 30 cents, enough to buy a new baseball at Alvinas store across the street from the Dumont Bar. While it was nice to have a pearly white baseball, the core of those cheap baseballs was made of sawdust, which meant the ball was lopsided after you hit it with a bat more than five times.