This book is dedicated to my daughter Jill, who was diagnosed with stage four neuroendocrine cancer about the time I started writing this book. She passed away on March 5, 2021 from neuroendocrine tumors. My proceeds from this book will be passed on to the Neuroendocrine Tumor Research Foundation (NETRF). Jills attitude and resilience in handling this horrific disease has been an inspiration to me. And to my many baseball friends, colleagues, and teammates who have left us in 2020 and 2021.

Contents

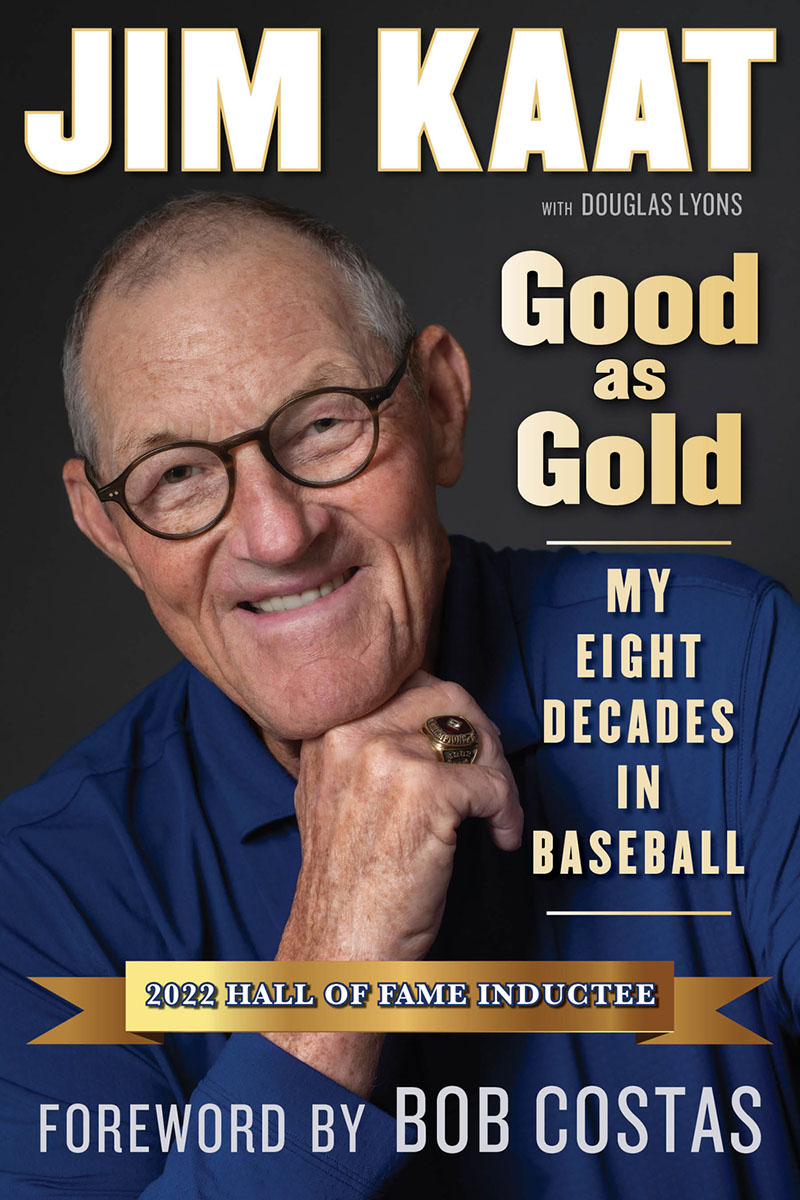

Foreword by Bob Costas

I guess I first saw Jim Kaat sometime in the early 60s, pitching for the Minnesota Twins against the New York Yankees on WPIX Channel 11 in New York. A rarity in baseball in those days, the Yanks televised the vast majority of their games, and growing up on Long Island, I watched nearly every one. I met Kitty in 1982. His long and winding big league career had taken him to my adopted hometown of St. Louis, where he helped the Cardinals win the 82 World Series. In our initial conversation, I recalled a 1967 game at the old Yankee Stadium, where Jim had the Yanks shut out, leading 10 with two out and nobody on in the bottom of the ninth. The hitter was Mickey Mantle, nearing the end of his career, hobbled and fading, but still dangerous, especially from the right side. These days, I am apt to forget where I left my glasses or keys, but back then, I remembered distinctly that the count was 31, and rather than walk him, Jim threw Mantle a fastball that caught too much of the plate. The ghost of greatness blasted it over the 457 sign in left-center, a sector of the ballpark reached only a handful of times in its history. The shutout and the lead were now gone.

At that point, I obviously didnt know Jim well, but he seemed a genial sort, so I was guessing he would not be put off by the implied invitation to relive the moment. Not only was I right about that, but Jim, a baseball man to his core, was genuinely pleased and engaged that a kid like meI was 30 but looked about half thatwould be so invested in a long-ago game, in which he and Mantle were the central figures. He told me that while Mickey Mantle was, well, Mickey Mantle, Elston Howard, who waited on deck, had been an equally tough out for him. (I checked: prior to the homer, Mantle had been 0 for his last 5 against Kaat. Howard had doubled in his previous at-bat that night.) So Kitty didnt want to face Ellie with a man on and the game on the line. He figured he would take his chances with Mantle, and unless he hit it down the line, the cavernous ballpark would hold it.

No such luck. But a lucky encounter for me, as Jim and I had hit it off right then. We both recalled that after the homer, with the ballpark and both dugouts still buzzing, Howard followed with a single up the middle. Jim then got the third out. Extra innings. But then came a heavy raina rain that would not stop. The game was called and went into the books as a 11 tie. A fateful turn of eventsbecause when the Twins returned to New York later that summer, Jim started the makeup game and was outdueled 10 by Steve Barber. The 67 Twins lost the pennant to the Boston Red Sox by one game. That one pitch to Mantle made a huge difference.

As it turned out, that random conversation between two baseball guys began what is now a nearly 40-year friendship, a friendship that became a professional partnership when Jim and I both joined the Major League Baseball Network at its inception in 2009. It was natural for us to be paired in the booth. Viewers tell us they can sense the ease and connection between us. It sounds like an ongoing conversation between friends, they say. And thats what it is: friends who share a lifelong love of the game. I have talked baseball with countless players, managers, and other baseball figures from old-timers to present-day stars. Very few are in Jims league as baseball raconteurs. His vast knowledge of the game and its colorful personalities; his still keen insights; and his firsthand experience over more than 60 consecutive years in the majors as player, coach, and broadcaster are a hard combination to match.

Credibility? Two hundred eighty-three wins. Three 20-win seasons, topped by 25 victories for the Twins in 1966. Sixteen Gold Gloves. And for good measure, 16 home runs as a hitter. All this spread over 25 seasons from 1959 to 1983. He was 44 when he threw his last big league pitch.

How much of baseball history does Jim Kaat span? I often kid him that you can connect him to Abner Doubleday in about three moves. Instead, lets try it this way: Jim faced Ted Williams, whose career began in 1939. He also faced Julio Franco, who lasted in the majors until 2007. A 68-year link right there. But wait: several currently active pitchers, including Adam Wainwright, Jon Lester, and Andrew Miller, faced Franco. Ted Lyons, the White Sox Hall of Famer, began his career in 1923. He faced, among other immortals, Ty Cobb, whose rookie year was 1905. He pitched in the American League into the 1940s and thus faced Williams many times. So there you have it: Cobb to Lyons to Williams to Kaat to Franco to Wainwright. Virtually the entire modern history of baseball in five moves.

No matter how you express it, Jim Kaat has been an admired and enduring citizen of the game. What follows is the story of a good portion of a remarkable baseball life.

Bob Costas

Introduction

I am one of the few people alive who can truly say that virtually every dollar I have earned as an adult has been because of my involvement in the game of baseball, a game I have loved since 1945, when I was about seven years old. Of course, I had multiple jobs as a teenager because fathers at the time encouraged their young sons to go get a job as soon as they could. As a teenager I stocked shelves and bagged groceries in a grocery store, sold clothes in Boonstras clothing store, swept floors in Tony Last Hardware store, and washed dishes at Boschs restaurant.

Even after I was a major leaguer in the early 1960s, I supplemented my income by doing some appearances and commercials for Cloverleaf Creamery in Minneapolis. In the first few years of my professional career, I announced high school football and basketball games for KSMM and KRSI in Minneapolis and I hosted some coaches shows. I had to because ballplayers at the time werent paid very much.

I am grateful that I have been blessed with the ability to play the game, coach the pitching part of the game, and for the last 35 years, to be a television analyst talking about the game I love more than any other. (I love golf too, but thats just a hobby.) I want to be perfectly clear that I have loved the special feeling the game of baseball has given me since 1945. Even today there is no topic that gives me more joy than sitting around with friends like Bill Parcells and Bryant Gumbel and playing baseball trivia or just talkin baseball.

But baseball has changed so much. And in many cases, in my opinion, not for the better. The appeal of the game is still the ability of the playersat a higher level than ever before. Theres more power and greater skill, agility, and speed. But it has decreased, in my opinion, in executing the fundamentals and in exhibiting in many cases a lower baseball IQ.

Pete Rose, the all-time hits leader, did not have much power, speed, agility, or even a strong throwing arm. But he was one of the greatest players of all time. Why? His baseball IQthe anticipation, the ability to see the whole field, knowing what every player needed to do, not just what he needed to do. Rose, the ultimate team player, played more than 500 games at five different positions: first base, second base, third base, left field, and right field. He could play according to the scoreboard. What inning is it? Whats the score? Whats the count? Whos pitching? Whos batting? How many outs? Those things dictated what a player should do in those situations. Not so much anymore. Keith Hernandez and Derek Jeter used to be great at that. Hernandez was my teammate with the St. Louis Cardinals from 1980 to 1982. You could see him thinking at first base. Jeter knew where he was and what was happening around him on every pitch.