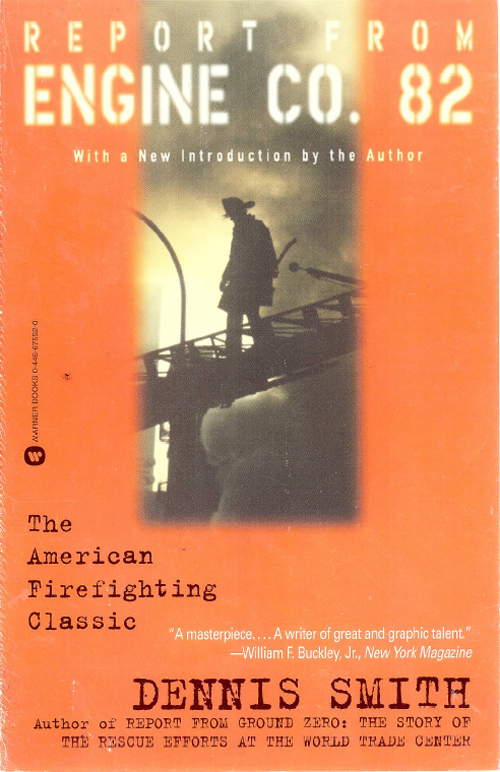

A real fireman and a writer of great and graphic talent, who explains to you and me firefighting as it isthe excitement, the horror, the tedium, the mysteries. A fine achievement.

William F. Buckley, Jr., New York Magazine

A blockbuster of a book. Read it.

Newsday

For the first time, a fireman tells it like it is.

Chicago Sun-Times

A moving profile of the people who keep Americas big cities from falling apart or burning down.

John Callaway, CBS Radio

Straightforward, graphic unsentimental, funny.

The New Yorker

A crackling book that captures the firefighters' camaraderie, heroism, and extraordinarily tough life.

National Observer

A terrifying, absorbing book.

Minneapolis Tribune

Has the urgency of a five-alarm fire.

Washington Post Book World

A Song for Mary: An Irish-American Memory

Final Fire

Glitter and Ash

Firehouse

Dennis Smiths History of Firefighting in America

The Aran Islands: A Personal Journey

Steely Blue

The Little Fire Engine that Saved the City (for children)

Firefighters: Their Lives in Their Own Words

Warner Books Edition

Copyright 1972 by Dennis Smith

Introduction copyright 1999 by Dennis Smith

All rights reserved.

This Warner Books edition is published by arrangement with the author.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-7595-2142-1

To the memory of all those firefighters in the

United States who have given their lives to protect us

more than 3,500 since the day I took the oath of office.

This book seems to be about a particular group of firefighters working in the South Bronx, but the incidents described here tell the story of all firefighters working in this country. The problems in Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and Los Angeles are the same, only the names change.

A book can develop a life of its own, and this is certainly true of Report from Engine Co. 82. When, almost thirty years ago now, I began keeping notes on my everyday experiences as a firefighter in the South Bronx, there was no way of knowing that I was creating a book that would be translated into a dozen languages, go through five editions and sell over two million copies.

Because of a letter Id published in the New York Times Book Review about the poet William Butler Yeats, a savvy editor of True magazine asked me to write an article about the life of a modern-day firefighter. While most beginning authors dream about ways to meet editors and literary agents, perhaps at school seminars, lectures, or weekly writing groups, here I was, never having met a person in the publishing industry, being invited to write a story for an important national magazine. What luck! It wasnt the only great good fortune Ive had in my life.

The events recounted in Report from Engine Co. 82 were something like a wartime experience, each day offering a new set of challenges. I remember thinking that the heroic men with whom I worked deserved a better chronicler than ITolstoy, perhaps, or Crane, or Remarque. I was just a neophyte, and the challenge of writing about great men was almost as frightening as that first time I pushed a hose line into a burning building. Yet, I knew I could do no more than my untested best.

Above all, finding the time to write required me to be innovative in scavenging time from my already busy days. While logging forty hours a week as a back-step firefighter, serving as father to three, working a side job as a limo driver to help pay the bills, and plugging away on a masters degree at New York University, I somehow found furtive moments to record what I saw each day amid the turbulence of the South Bronx.

Engine Company 82, where I worked from 1966 to 1973, was then the busiest fire company in the most desperate neighborhood of the countrys largest city, a place where the American records were held for crime, poverty, illness, and deprivation of all kinds. The South Bronx also held the record for fires. Engine Company 82 responded to about nine thousand alarms each year, about a third of them for emergencies like shootings, knifings, car accidents, suicides, drug overdoses, and any one of a hundred terrible things that can happen to a person who has no money, no education, no job, and no future.

The next third were false alarms, a strange but predictable by-product of the lawlessness and ignorance that inhabits impoverished neighborhoods. The random and seemingly innocuous pulling of a false alarm can and often does end up being an act of malicious criminal manslaughter, for when the fire trucks are responding to a false alarm at one end of the district, theyre unable to save lives at the other.

The final third were the alarms for fire. In our district alone, an average day brought about ten or twelve fires, almost all of them deliberately set. Two or three each day grew into second, third, or fourth alarm fires that entailed heavy risk for the firefighters trying to contain them. The South Bronx was a dangerous place, and even today Im not sure whether it was more dangerous for the firefighter or the average citizen.

Katherine Anne Porter once suggested that sometimes a book will find its author, rather than the other way around, and I think thats true of this book. The story of the extraordinary and selfless work of firefighters needed to be told; by happenstance, I wanted to be a writer, I wore a helmet already dark with the soot of a hundred fires, and I worked in the busiest fire company in the history of the New York Fire Departmentand perhaps the world. So a book that needed to be written found me.

Not long after my letter appeared in the Times, The New Yorker published an article about me titled Fireman Smith in which 1 discussed literature in general and William Butler Yeats specifically. This article in turn prompted an editor at McCall Books to query whether Id ever considered writing a book about being a firefighter. I responded like, well, a fireman responding to an alarm. I knew that before me was a story few people knew, and I felt challenged by the act of writing the way mountain climbers are confronted by mountains.

I loved writing about the never-ending excitement, the bravado of the firefighters, and the countless stories of human adversity and trial. Some days I found myself sitting on the edge of my chair as excited by the writing as by a fourth alarm fire. When the last sentence was typed, I felt my modest goal had been accomplished: to honestly depict the everyday trials of an urban fireman.

The 1960s was a tempestuous period for America, a time that might be remembered as the age of riots. The Burn-baby-burn syndrome, coupled with a growing distrust of any authority figurebe it government, police officers, or firefightersled to a historically high rate of fire. And in the deprived, impoverished world of the South Bronx, people believed it was better to burn the neighborhood called ghetto than to continue to acquiesce in its everyday life.

Three decades later, I returned to the streets of the South Bronx, accompanying the fire chief as he worked the night shift. As I studied the look, the smell, and the feel of the streets, I realized so many things had not changed: families living in unkempt, inadequate housing, filthy alleys and backyards, the polluted air that comes with overcrowding. The firefighters, though, are responding to far fewer fires than before, mostly due to a heightened intolerance of crime and the dissipation of the radical political mentality of the Vietnam era. Engine Co. 82 now responds to about 3,800 alarms a year, down from 9,000 when this book was written. Yet, the firefighters still crawl through garbage- and debris-smutted hallways, still respond to false alarms at three, four and five oclock in the morning, still confront abandoned buildings torched by mercenary landlords, and still hear the frantic screams of mothers whose children might be left behind in burning buildings.