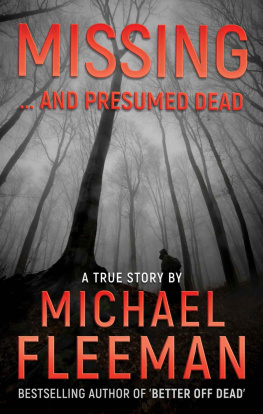

MISSING

... AND PRESUMED DEAD

A TRUE STORY BY

MICHAEL FLEEMAN

WildBluePress.com

MISSING AND PRESUMED DEAD published by:

WILDBLUE PRESS

P.O. Box 102440

Denver, Colorado 80250

Publisher Disclaimer: Any opinions, statements of fact or fiction, descriptions, dialogue, and citations found in this book were provided by the author, and are solely those of the author. The publisher makes no claim as to their veracity or accuracy, and assumes no liability for the content.

Copyright 2019 by Michael Fleeman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

WILDBLUE PRESS is registered at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Offices.

ISBN 978-1-948239-96-7 Trade Paperback

ISBN 978-1-948239-97-4 eBook

Interior Formatting/Book Cover Design by Elijah Toten

www.totencreative.com

Table of Contents

FOREWORD

We can determine the young womans final actions from the electronic signals sent to and from her cell phone. At 1:35 a.m., we know, her phone rang. Global Positioning Satellite data placed her location within an accuracy of a few feet to an apartment building on River Oaks Drive in North Myrtle Beach, S.C., where she lived with a roommate.

Up popped a local 843 number that matched no name in her list of contacts. Call records later obtained from the Frontier Communications linked that number to one of the nations few operating pay phones, outside a Kangaroo Express gas station on the corner of Seaboard Street and 10th Avenue in Myrtle Beach.

The call lasted about four minutes and left her crying hysterically, a fact a jury would know only because a defense attorney would later fail to lodge a hearsay objection.

We know she called back the pay phone three times in rapid succession, never getting an answer, suggesting a frantic need to make a connection.

She then got into her car, a 2001 Dodge Intrepid registered to her father, and drove to a nearby restaurant called Longbeards Bar & Grill on Carolina Forest Boulevard. She pulled into the corner of the dark parking lot. GPS put her near the Dumpsters. She called the pay phone back four more times, again getting no answer.

She next drove to the entrance of a housing development called Augusta Plantation down the street, then returned to Longbeards, and called the pay phone twice morefor a total of nine fruitless attempts at reaching somebodybefore returning to her apartment. She may have stayed outside on the street. She may have gone inside.

It was now 3:16 a.m., a moonlit night, according to the National Weather Service.

She dialed another local 843 number. This one did come from a contact in her phone, one that she had once exchanged phone calls and text messages more than 1,000 times, but that she hadnt called in weeks.

Nobody answered. She dialed again at 3:17 a.m. and got a connection. The call lasted for 4:15 minutes. She then immediately started driving. GPS followed her down White River Road, to Forest Brook Road to Peachtree Road, a narrow, one-way road.

There she stopped.

She made more calls, got no answers. The last call was recorded at 3:41 a.m.

GPS data placed her final stop at Peachtree Landing, with nothing around her but the murky waters of the Waccamaw River and, beyond that, forest and wetlands, what a prosecutor later called one of the darkest holes in Horry County.

We can only infer all this because of the limitations of modern technology. We know what phones called what numbers at what times from what locations.

To determine who actually spoke on those phones, we need witnesses, a confession, and additional physical evidence such as DNA, blood, hair, and fingerprints.

We didnt have that. All we would know was from that point on, nobody has seen or heard from Heather Elvis again.

Around 4 a.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 18, 2013, Casey Guskiewicz pulled his Horry County Police Department cruiser down Peachtree Road to the boat launch. Guskiewicz was in the final stretch of his 5:45 p.m. to 6 a.m. graveyard shift, on routine patrol, driving solo through Sector 14 in the Central Precinct, ensuring the safety and lives and property of Horry County, hed later say in court.

A barrel-chested man with his brown hair in a military cut, Guskiewicz was in uniform: gray shirt with black epaulets, and shoulder patch bearing a hilltop farmhouse overlooking a stream and the beach with a cheery yellow sun.

His route took him down lonely country roads lined with telephone poles, mobile homes on grassy lots, mailboxes on posts, and dirt roads marked private road. He passed the Sweethome Freewill Baptist Church with a pitched roof and brick walls, and neat white homes on big lots.

A turn at Peachtree Road plunged him into the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge. Houses stood on stilts due to periodic flooding of the Waccamaw River.

A stop sign emerged in the darkness. Without it, a person unfamiliar with the area would drive straight into the water, he recalled. Just past the stop sign, the ramp descended into the Waccamaw River section of the Intracoastal Waterway. On either side of the landing were parking spots. To the east was a small trailer park with a half-dozen residences. To the west was nothing but swamp, he said.

There he saw a dark-colored Dodge Intrepid sedan. It was parkedawkwardly was the word he usedin the middle of the boat landing facing the river. He shined his headlights on the car so he could make out the license plate. He ran the tags on his in-car computer and the Dodge came back clean, not stolen.

He walked up to the car and shined his flashlight through the drivers side rear window. The car was locked. He didnt see anybody in the front seat or the back. He didnt see any keys in the ignition or any sign of a cell phone on the seats. The seats and floorboards were littered with papers and what looked like food wrappers.

Guskiewicz scanned the landing. Not a soul. He shined his flashlight into the swamp on his right, shined it across the river. No boats, no nothing, he said.

After five or six minutes, he left without calling it into the station, without filing a report, without notifying the registered owner. It was just a vehicle parked at a boat landing, he said. Something hed seen many times on his rounds.

Ominous at night, by day, the landing is known as a quiet, pleasant, picturesque spot in the county, a jumping off point for boating and fishing, where families would come for picnics and day trips on the Waterway. People left their cars there for days sometimes. Some parked them more considerately than others.

Shortly after 4 a.m., he left the landing to complete his rounds.

He may have missed Heather Elvis by less than a half-hour.

The Dodge Intrepid sat at the landing all through a cold and gray Dec. 18 and Dec. 19, when few, if any, boaters used the landing, until at 5 p.m. on the 19th, somebody reported it to police.

Kenneth Canterbury, a patrol officer in the south precinct of Horry County Police Department, which covers Socastee, Myrtle Beach, Zuman, and Surfside, took the call of a suspicious vehicle.

Peachtree Landing didnt fall into his usual patrol routehe was in a different precinctbut he responded anyway. He drove down the same roads that Guskiewicz had taken that morning, arriving at the landing, he estimated, just after sunset, which the National Weather Service recorded as 5:10 p.m.

Burly and buzz-cutted, Canterbury could be Guskiewiczs brother. He saw the same dark Dodge Intrepid parked in the same haphazard fashion. Using his flashlight, he found the same lack of damage, the doors locked, the car empty, and the inside cluttered with paper. He, too, ran the tag. Not stolen, but registered to a name he recognized: Elvis.

Next page

![Dzhejms CHejz - Safer Dead [= Dead Ringer]](/uploads/posts/book/910100/thumbs/dzhejms-chejz-safer-dead-dead-ringer.jpg)