The story of South Carolinas geography begins with the Appalachian Mountain chain. Its in Appalachia where so much of the coasts freshwaterin the form of raincomes together and flows southeastin the form of riversto the Atlantic Ocean. A feature called the Blue Ridge Escarpment, or Blue Wall, demarcates the mountains, and its steep face is responsible for most of the many waterfalls in the state.

Moving east, the next level down from the Appalachians is the piedmont region (in South Carolina often called simply the Upstate). The piedmont is a rolling, hilly area, the eroded remains of an ancient mountain chain now long gone.

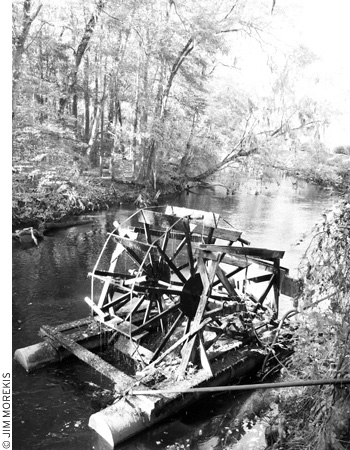

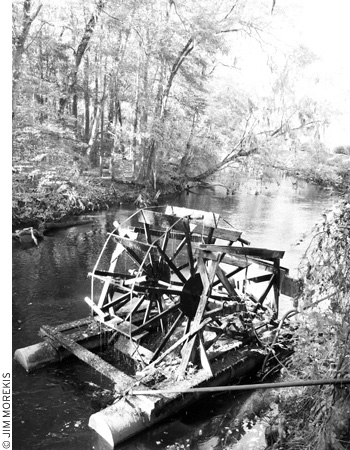

At the piedmonts eastern edge is the fall line, so named because its there where rivers make a drop toward the sea, generally becoming navigable. This slight but noticeable change in elevationwhich actually marked the shoreline about 60 million years agonot only encouraged trade but has provided water power for mills for hundreds of years. Many inland cities of the region, like Columbia, trace their origin and commercial success to their strategic location on the fall line.

The Edisto River is the longest blackwater river in the world.

Around the fall line zone in the Upper Coastal Plain you can sometimes spot sand hills, usually only a few feet in elevation, generally thought to be the vestigial remains of primordial sand dunes and offshore sandbars. Well beyond the fall line and the sometimes nearly invisible sand hills lies the lower coastal plain, gradually built up over a 150-million-year span by sedimentary runoff from the Appalachian Mountains, which were then as high or even higher than the modern-day Himalayas.

The coastal plain was sea bottom for much of the earths history, and in some eroded areas you can see dramatic proof of this in prehistoric shells, shark teeth, fossilized whale bones, and oyster beds, often many miles inland. In some places, calcium from these ancient shells has provided a lush home for distinct groups of unique plants, called disjuncts.

At various times over the last 50 million years, the coastal plain has submerged, surfaced, and submerged again. At the height of the last major ice age, when global sea levels were very low, the east coast of North America extended out nearly 100 miles farther than the present shoreline. (We now call this former coastal region the continental shelf. ) The Coastal Plain has been in roughly its current form for about the last 15,000 years.

Rivers

Visitors from drier climates are sometimes shocked to see how huge the rivers can get in the South, wide and voluminous as they saunter to the sea, their seemingly slow speed belying the massive power they contain. South Carolinas big alluvial, or sediment-bearing, rivers originate in the region of the Appalachian mountain chain.

The blackwater river is a particularly interesting Southern phenomenon, duplicated elsewhere only in South America and one example each in New York and Michigan. While alluvial rivers generally originate in highlands and carry with them a large amount of sediment, blackwater riversthe Edisto River being the chief exampletend to originate in low-lying areas and move slowly toward the sea, carrying with them very little sediment. Their dark tea color comes from the tannic acid of decaying vegetation all along the banks, washed out by the slow, inexorable movement of the river toward the sea. While I dont necessarily recommend drinking it, despite its dirty color, blackwater is for the most part remarkably clean and hygienic.

Carolina Bays

An interesting regional feature of the state is the Carolina bay, an elliptical depression rich with biodiversity, thousands of which are found all along the coast from Delaware to Florida. While at least 500,000 have been identified, new laser-based imaging technology is enabling the discovery of thousands more, previously unnoticed.

Though not all Carolina bays are in the Carolinas, many are, and thats where they were first documented. Theyre called bays not for the water within themindeed, many hold little or no water at allbut for the proliferation of bay trees often found inside. Carolina bays can be substantially older than the surrounding terrain, with many well over 25,000 years old. Native Americans referred to the distinctive wetland habitat within a Carolina Bay as a pocosin.

Theories abound as to their origin. One has it that theyre the result of wave action from when the entire area was underwater in primordial times. The most popular, if unproven, theory is that they are the result of a massive meteor shower in prehistoric times. Certainly their similar orientation, roughly northwest-southeast, makes this intuitively possible as an impact pattern. Further bolstering this theory is the fact that most Carolina bays are surrounded by sand rims, which tend to be thicker on the southeast edge.

An old theory, once discredited but now gaining new credence, is that Carolina bays are the result of a disintegrating comet that exploded on entry into the earths atmosphere somewhere over the Great Lakes. Apparently, if you extend the axes of all the Carolina Bays, thats where they converge. This theory takes on an ominous edge when one realizes that the same comet is also blamed for a mass extinction of prehistoric animals such as the mammoth.

The Intracoastal Waterway

Youll often see its acronym, ICW, on signsand sadly youll probably hear the locals mispronounce it intercoastalbut the casual visitor might actually find the Intracoastal Waterway difficult to spot. Relying on a natural network of interconnected estuaries and channels, combined with artificial cuts, the ICW often blends in rather subtly with the already extensive network of creeks and rivers in the area.

Mandated by Congress in 1919 and maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Atlantic portion of the ICW runs from Key West to Boston and carries recreational and barge traffic away from the perils of offshore currents and weather. Even if they dont use it specifically, kayakers and boaters often find themselves on it at some point during their nautical adventures.

Estuaries

Most biologists will tell you that the coastal plain is where things get interesting. The place where a river interfaces with the ocean is called an estuary, and its perhaps the most interesting place of all. Estuaries are heavily tidal in nature (indeed, the word derives from aestus, Latin for tide), and feature brackish water and heavy silt content.

South Carolina typically has about a 6-8-foot tidal range, and the coastal ecosystem depends on this steady ebb and flow for life itself. At high tide, shellfish open and feed. At low tide, they literally clam up, keeping saltwater inside their shells until the next tide comes.

Waterbirds and small mammals feed on shellfish and other animals at low tide, when their prey is exposed. High tide brings an influx of fish and nutrients from the sea, in turn drawing predators like dolphins, who often come into tidal creeks to feed.

Its the estuaries that form the most compelling and beautiful sanctuaries for the areas incredibly rich diversity of animal species. Many estuaries are contiguous with those of other rivers; Charleston Harbor, formed by the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, is an excellent example of that phenomenon.

Salt Marsh

All this water action in both directionsfreshwater coming from inland, saltwater encroaching from the Atlanticresults in the phenomenon of the salt marsh, the single most recognizable and iconic geographic feature of the South Carolina coast, also known simply as wetlands. (Freshwater marshes are rarer, Floridas Everglades being perhaps the premier example.)