Legends of the Superstition Mountains

By

Charles A. Mills

Legends of the Superstition Mountains

By Charles A. Mills

Copyright 2019, Charles A. Mills

T he Superstition Mountains of Arizona, the Legend of the Lost Dutchmans Mine, and the Peralta Stones are inextricably linked. The entire story supposedly began in 1748 when the Peralta family are said to have started mining silver and gold in the Superstition Mountains. During the Mexican War (1846-1848), law and order disintegrated in the area and the Apache Indians grew increasingly hostile, attacking the miners almost continuously. It is said that disaster finally overtook the Peralta family in September 1848, with a general massacre by the Apaches. Following this massacre, the Apaches controlled the Superstition Mountains until 1865. Supposedly after the massacre of 1848, the Indians filled the mine shafts and disguised the remains.

Jacob Waltz, the Dutchman, enters the picture in 1871 with his partner Jacob Weiser. The two immigrants supposedly purchased a map drawn by the original Peralta family and located the mine, within an imaginary circle whose diameter is not more than five miles and whose center is marked by the Weavers Needle. Weiser soon vanished...the victim of either Indians, desperados or Waltz, depending on which story you want to believe. The Dutchman continued working the mine, carrying the secret of its location to the grave with him in 1891.

For over fifty years after the death of Waltz, treasure hunters followed the ambiguous clues that the Dutchman left behind as to the whereabouts of the mine, such as these helpful clues:

No miner will find my mine. To find my mine you must pass a cow barn. From my mine you can see the military trail, but from the military trail you cannot see my mine. The rays of the setting sun shine into the entrance of my mine. There is a trick in the trail to my mine. My mine is located in a north-trending canyon. There is a rock face on the trail to my mine.

Something significant changed in 1949 when the so-called Peralta Stones were discovered in the desert. A Mexican bracero (a legal migrant laborer) was digging fence posts near Black Point, in Pinal County, when he came across a large flat stone. He dug the stone out only to find that it was covered in strange writing. He recognized a Spanish word, Indian petroglyphs, and some Spanish markings. In all, the bracero dug up three stones carved with writing and a crude map. The bracero hauled the curious stones into Florence Junction, three miles away, where he washed them, and prepared to sell the curious stones to any willing tourist who might come along. Robert G. Tumlinson (or Travis E. Tumlinson depending on who is telling the story) of Portland, Oregon, turned out to be that tourist. The bracero pocketed the equivalent of a weeks wages, and Tumlinson drove off with the stones. Tumlinson went on to Phoenix, to visit his brother. The two brothers thoroughly washed the rocks and examined them, determining that what they were looking at was some kind of coded map.

There a number of variations on exactly how, where and by whom the Stones were discovered, but many Dutch Hunters believe that the Stones refer to the location of the Lost Dutchmans Mine and that they were carved by the Peralta family. The Stones consist of two red sandstone tablets and a heart-shaped rock made of red quartzite. Each red stone block is carved with lines and one long line. When the two blocks are placed side by side and the stone heart is inserted, the long line has eighteen dots pecked into it. This style of map is known as a Post Road Map and is a style of map used in Mexico and Spain during the period of the Mexican-American War. Inscribed on one of the stones is the date 1847, and one stone contains a sunken relief of a heart, into which the heart-shaped stone fits perfectly. The back of the stone that the heart-shaped stone fits into has the outline of a cross carved into it.

Apparently, Tumlinson spent a number of years in the Superstition Mountains trying to track down clues from the Stones. The Stones emerged again in the early 1960s, after Tumlinsons death. One Clarence O. Mitchell persuaded Tumlinsons widow that he could decipher the stone maps. Mitchell organized the M.O.E.L. Corporation in Nevada and began a stock selling campaign among his friends and close associates to raise capital for the treasure expedition. Mitchell raised more than $70,000 over a two-year period. Eventually Mitchell ran into difficulties with the Securities and Exchange Commission for over selling the number of shares the corporation had issued, and for selling unregulated stocks. The corporation was forced into bankruptcy.

In 1964, freelance writer Richard B. Stolley sold a story about the stone maps to Life magazine. The article provided the first public photographs of the Peralta Stones (although certain markings on the maps were covered by black tape). These photographs inflamed the nations imagination.

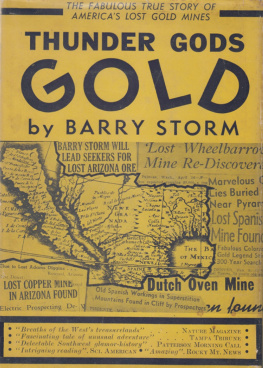

In 1967, Barry Storm, the Dean of American Treasure Hunters, wrote an article for Treasure Hunters magazine relating his attempts to decipher the stone maps. This article was followed by a variety of other writers, photographers, film makers and con men who have since used the Peralta Stones as a justification for seeking treasure in the Superstition Mountains.

So the real question is, Are the Peralta Stones real or fake? Do they present genuine clues or phony clues? For more than seventy years the Peralta Stones have been the subject of heated controversy. Over this time period those whove studied the maps have remained firmly and pretty evenly divided into two separate camps: (1) those who believe and (2) those who do not believe. It does not appear that this will change anytime soon.

The arguments and counterarguments run like this:

Proposition: The Peraltas never mined gold in the Superstition Mountains.

Nonbelievers point out that: There are no historical records indicating that the Peralta family carried out mining operations in the Superstition Mountains. Some say that the origin of the legendary Peralta story can be traced to a newspaper article which appeared in the Arizona Daily Herald in 1879. This article described the ordeal of two Mexican prospectors, brothers named Miguel and Pablo Peralta, who were attacked by the Apaches west of the Superstition Mountains. Pablo died of his wounds, while the surviving brother was able to carry out a bag of rich grade gold ore. This incident occurred thirty years after the Peralta Stones were supposedly buried, but was seized upon and altered by a newspaper writer named Pierpont Bicknell in 1895 to liven up a story he was writing about the Lost Dutchmans Mine. In short, Bicknell was not going to let a few pesky facts get in the way of a good story. He invented the story of the Peralta mines in the Superstitions. Bicknells January 13, 1895, story in the San Francisco Chronicle figured importantly in giving credence to the legend of the Lost Dutchmans Mine. Bicknells article also created the foundation for both the story of the legendary Peralta mines, and the later story of the Peralta Stones. Future writers such as Oren Arnold, author of Superstitions Gold , and noted treasure hunter Barry Storm, latched onto and expanded upon Bicknells original story.

Next page