Published by Guardian Books 2012

ISBN: 978 085265 2589

Version 1.0

Copyright Guardian News and Media 2012

Introduction by and edited by John Stern

Designed and set by Two Associates

All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Guardian Books.

The Guardian iPad edition

http://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/guardian-ipad-edition/id452707806?mt=8

The Guardian iPad edition showcases our comprehensive international reporting, thoughtful commentary, award-winning sports journalism and unique approach to coverage of culture, science and technology. The newspaper completely re-imagined for iPad with stunning full-screen photojournalism and cartoons - it downloads within a minute via Wi-Fi for a complete reading experience even when you dont have a signal.

GUARDIAN SHORTS bring you the very best of our journalism, comment and analysis, from breaking news to the seasons sports and culture.

Introduction

By John Stern

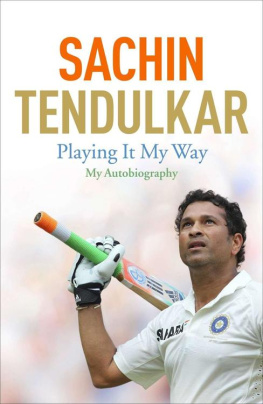

India had just won the World Cup and the Wankhede Stadium in Mumbai was in a state of delirium. The players had completed a lap of honour during which they had carried Sachin Tendulkar on their shoulders.

Virat Kohli, the young Indian batsman, was asked by a television interviewer the significance of such an act. Hes been carrying the burden of a nation for 21 years so its about time we carried him, said Kohli, a comment that would have been notable for its pithiness at any time but was all the more remarkable given the emotion of the moment.

Kohlis assessment was entirely correct and explains why Tendulkar is unlike any cricketer who has ever lived, with the possible exception of Don Bradman. Sachin Tendulkar bears a burden greater than possibly any sportsman of any age, wrote Rahul Bhattacharya in the Guardian in 2002.

The favourite clich is that cricket in India is a religion and Tendulkar is God. Not just a deity, but the only one. When he bats a billion Indians tune in. Stadiums fill when he comes to the crease. High-class batsmen ahead of him in the batting order have been booed because the crowd cannot wait to see Sachin. And when he is out, the ground will often empty as quickly as it filled.

It is 22 years since Tendulkar was first properly admired by the cricket writers of The Guardian and Observer, when on his first tour of England he made a maiden Test hundred at Old Trafford. His greatness, though, had already been foretold from the time when he and a school pal Vinod Kambli compiled a partnership of incomprehensible magnitude, 664. His was not a gradual emergence, a steady climb to global stardom. He just arrived, as if born to bat, which makes his success and longevity all the more staggering.

From his mid-teens he has lived his life in public. In India and many other parts of the world, he cannot walk freely. He must be accompanied everywhere by a posse of security guards. In the midst of this ring of muscle you might just about spot Sachin, a small man the same mop of curly black hair as he has always had, the same modest smile, tolerant, humble and determined.

It has not been a flawless career. There have been suggestions that he has cared more for records than team victories, that his batting is mechanical and soulless rather than explosively brilliant like the Trinidadian Brian Lara, a contemporary who lacked Tendulkars consistency but had more appealing peaks and troughs. There was a seemingly terminal dip in form in the mid-2000s before a late career rebirth. He was even reprimanded for ball-tampering in late 2001.

The Guardian and Observer possess some of the finest writers on cricket in the history of a sport noted for its literary inclinations and rich human narratives. Many of these writers have played the game at the highest level too, though none, with due respect, at quite the level of the subject of this collection. Some, like Steve James, Angus Fraser and the some-time Guardian columnist Ian Bell, have played against Tendulkar. Others like Mike Selvey, Vic Marks and Mike Brearley, all former England cricketers, have observed his feats at close quarters since the beginning.

Then there are the professional journalists: Matthew Engel, the Guardians former cricket correspondent and Wisden editor, David Hopps, Tanya Aldred and even the glorious David Foot, who rarely ventured east of Bristol but luckily got to see our hero in action when the World Cup came to England in 1999. The talented young Indian writers Rahul Bhattacharya and Dileep Premachandran provide context and perspective. Tendulkar has generally let his batting speak for him but he is quoted liberally throughout this ensemble and we also republish a recent interview with him by the award-winning Donald McRae.

This collection cannot claim to be comprehensive. It is inevitably Anglocentric, focusing on Tendulkars performances in or against England and in World Cups. Lets not forget his pioneering jaunt in Yorkshire, which is told beautifully in a before-and-after double-header by Engel and Hopps.

His outstanding performances in Australia dont quite get the treatment they deserve, in particular his 114 in Perth in 1992. He regards the innings as one of his best, Wisden described it as captivating. He was only 18, the Perth pitch was one of the paciest in the world and the next highest score in the innings was 43, made by the wicket-keeper Kiran More batting at number ten.

He batted with a freedom and a flair at the start of his career that he gradually sand-papered down into a groove of relentless accumulation. As injuries took their toll in his mid-30s, he was fading before rediscovering the joy of batting that was stifled only by the intense, and self-imposed, pressure to reach the numeric milestone of a hundred international hundreds. The milestone finally came in March 2012 after a severe case of the nervous 99s he completed the feat against Bangladesh in Mirpur 12 months after his 99th century, against South Africa during the World Cup.

My own personal preference would always have been to spend by last tenner on watching Lara rather than Tendulkar. For the non-partisan observer, he possessed a greater capacity to thrill, matched predictably by an ability to frustrate and exasperate.

But as Tendulkar has comfortably outlasted Lara and continues to play innings of style and substance, I find myself reappraising him. He is a sporting phenomenon the like of which and this is a very dangerous thing to say we will surely never see again. Next on the list of century-makers in international cricket is the Australian Ricky Ponting. He has 71 hundreds to Tendulkars 100. Enough said.

Timeline

Feb 1988 Aged 14, puts on a 664-run unbroken stand with Vinod Kambli, 16, in a school match in Bombay.

Dec 1988 Makes a hundred on his first-class debut, aged 15.

Aug 1990 At 17 years and 112 days, becomes the second-youngest century-maker in Test history with 119 not out against England at Old Trafford.

Feb 1992 Plays what remains one of his finest Test innings, 114 against Australia at Perth.

Apr 1992 Becomes Yorkshires first overseas player.

Nov 1992 At 19 years and 217 days, becomes the youngest player to reach 1,000 Test runs.

Feb-Mar 1996 Leading run-scorer (523 runs at 87.16) in the World Cup held in Asia.

Aug 1996 Aged 23, he becomes captain of India for the first time. His first tenure lasts 15 months.