GUARDIAN SHORTS bring you the very best of our journalism, comment and analysis, from breaking news to the seasons sports and culture.

Written by Simon Hattenstone. Designed and set by Guardian Creative.

All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Guardian Books.

The Guardian iPad edition showcases our comprehensive international reporting, thoughtful commentary, award-winning sports journalism and unique approach to coverage of culture, science and technology. The newspaper completely re-imagined for iPad with stunning full-screen photojournalism and cartoons - it downloads within a minute via Wi-Fi for a complete reading experience even when you dont have a signal.

Prologue: How to Interview

The essential requirement for being a decent interviewer is nosiness. Youve got to be a voyeur of the highest, or lowest, order. An interviewer cannot be a respecter of boundaries. An interviewer must be a supreme invader of privacy.

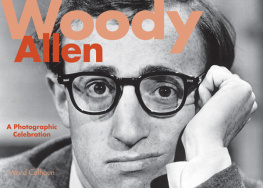

O ccasionally I can dress up questions with a public-interest defence, but to be honest I know it doesnt wash when, say, Im asking Willem Dafoe if its true he has the biggest penis in Hollywood, or Glenda Jackson whether anything in politics can match having her nipples sucked by Oliver Reed, or Woody Allen how he does so well with women when hes so plain looking. (I was going to say ugly, but couldnt bring myself to.)

Of course, these are extreme examples. Im showing the worst side of myself. I could just as easily talk about asking Desmond Tutu about his faith helped him through apartheid, Stevie Wonder about the relationship between blindness and his music, Philip Gould about his impending death, Paddy Hill about being locked up for 16 years for murders he did not commit, Duwayne Brooks about seeing his friend Stephen Lawrence killed. But you still come up with the same answer. Nosiness. Interest in people. If you find people boring, this is not the career for you.

I love my job, and not simply because its a pryers delight. For all its mucky intrusiveness, interviewing is a noble art. My favourite interviews say, David Frosts with Richard Nixon or Melvyn Braggs with Dennis Potter help us understand people, humanise them, open up the world to us. And by understanding how others get through life, we can make more sense of our own struggles.

There are many different ways to interview. You can be a silent confessor figure, an interrogator, a casual chatter. You can be unctuous, hostile, neutral, formal, anarchic. You can give nothing of yourself (Lynn Barber famously told one subject she had no children because she felt it was a distraction and it would eat into her time) or splurge out your whole life story in the hope that your subject will give you something back in return. The journalist Ginny Dougary says, I think of interviewing more as going into battle than a seduction... the skilled interviewee will try to give the impression of revealing everything while, actually, giving nothing away; the skilled interviewer has to be super-alert to these tricks and dig deeper, always dig deeper. Often interviewers will use all these techniques at some time in their career, depending on the individual. Even if you are being more empathetic or aggressive than you might normally be in real life, you should stay true to your basic self.

Interviews can succeed on so many levels. They can be beautifully written, stuffed with outrageously good quotes, a confrontation between two gladiators. They can contain a single descriptive nugget that comes to define the interviewee, or brilliantly illustrate the relationship between subject and their work.

Britains first known interview appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1884. It became known as the new journalism and was sneered at as a sycophantic and melodramatic form. But editor WT Stead felt vindicated when his interview with Chinese Gordon about imperial policy in the Sudan resulted in the Gladstone government sending Gordon to Khartoum Stead crowed that he ran the empire from the offices of the Pall Mall Gazette.

It was in the 20th century, with the evolution of newspaper, radio and television, that the interview blossomed. There was a healthy, relatively equal, relationship between interviewer and interviewee interviewees needed the oxygen of publicity; most interviewers felt they had a responsibility to report the truth. In the 21st century, the interview is a dying form stars say what they want on their websites, and make myriad ridiculous demands before agreeing to interviews.

Its understandable why so many people in public life refuse to subject themselves to the print interview. After all, it is one of the most subjective, unregulated areas of journalism. Sure, you accurately quote your subject, but its the interviewers call on what to include, what to miss out, how to sew the quotes together to create a narrative. I used to argue with my friend and former editor Helen Oldfield, who would often say But whats the story, hon?, petulantly crying There isnt one its just somebody talking about his/her life. But she was right. There has to be a narrative of sorts in an interview: you have to guide the reader from beginning to end, however loosely or elliptically. For me, though, the danger is forcing the subject into a narrative straitjacket that you have designed for them. I much prefer it as a reader (and writer) when you are taken on a journey but youre not sure where youre going or how youre going to get there. I love pieces that leave readers to draw their own conclusions.

Print interviews can be flat and dull a series of unconnected quotes loosely strung together. The best print interviews are riveting, pacy, moving, shocking and highly visual. When I start to write up an interview I hope to open the door and invite the reader into the room to share the exchange. The biggest compliment a reader can pay me is to say I felt as if I was there.

Simons top 10 tips for a successful interview

1. Do your research.

Go back to the earliest available cuttings. When somebody is young and less media savvy, they are more likely to tell the truth about themselves. When I interviewed Helen Mirren I asked her about sex and sexuality because it played such a huge part in her work. She looked at me with contempt and said I was just another sad man projecting fantasies on to her. I felt more than a bit diminished. It was only when I referred to a cutting from one of her first interviews, in which she had talked about the risqu photographs she had taken with her photographer lover and how she hoped they would never find their way into the public domain, that she admitted she had been interested in fetishism and all kinds of stuff.

2. Ask your friends what they want to know.

Remember, you are there as a representative of everybody else. Normal people, particularly fans, might have more fresh questions than have been asked in previous interviews. Before I interviewed Woody Allen, a friend asked me to ask him how come he did so well with women when he was so ugly. A tough ask. Every time I approached the question I demurred, and asked a real toughy like So Woody tell me why whats your favourite film? Eventually I did ask, but changed ugly to plain-looking. He loved the question because he had dedicated his whole life to women and wooing them, and had wondered much the same thing. He gave the following masterclass of an answer: