PREFACE

You almost had to know all of us to know any of us.

It Was the Players Game Then

O n black-and-white televisions, in a black or white time, men played football for something less than a living and something more than money. They didnt deny the attractiveness of money. On their own scale, they were as venal a collection of chiselers and money-grubbers as professional athletes are today. But they were football players first. If the Browns cut them in Hiram, Ohio, they hitchhiked to Westminster, Maryland, to try out for the Colts; and if Baltimore had no use for them either, they would play for the Annapolis Colts, or the Bloomfield Rams. If the sandlots were full, they might form their own semipro team and call themselves the Antioch Hornets. They were going to play football.

Most of them were white; a few were black. (Black-and-white is their color, all right.) On average, the white ones were just about as bigoted as the country. Yet there were surprising incidents of enlightenment, fellowship, even brotherhood. The pro football players of the 1950s were regular guys who, by and large, stayed regular guys. They were slightly less famous, somewhat less prosperous, than the baseball players. But literally and figuratively, they were in the same ballpark. When the World Trade Center crashed down on September 11, 2001, among the small, exquisite details was the fact that Carl Furillo, retired batting champion of the Brooklyn Dodgers, had worked in the construction of the Twin Towers, installing Otis elevators. Todays pro athletes wont be installing any elevators. Thats the thing that sports will never get back. Once, the players were one of us. They lived right next door. They dont anymore.

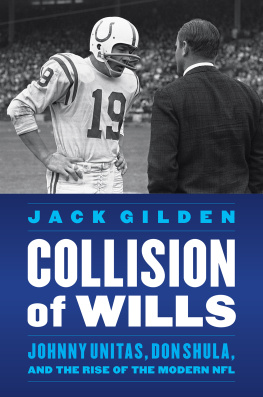

On September 11, 2002, the first anniversary of that horror, the legendary quarterback Johnny Unitas died of a heart attack. He was a football player, said Unitass primary receiver, Raymond Berry. Those words dont look like much on the page, but you should have heard Berry say them. Unitas was the football player, said Sam Huff, an old linebacker for the New York Giants. The best player of Huff, Berry, and Unitass dayand maybe of any daywas Cleveland fullback Jim Brown, who, in a conversation with the writer George Plimpton, once mentioned a Pro Bowl practice conducted by Giant coach Allie Sherman. All right, Sherman called out across the field, lets have the first team offense over here. But no lists of first or second strings had been posted. Every player present was a starter and a star. Nevertheless, one by one, with scarcely a word spoken, hardly a glance exchanged, eleven of them moseyed over and took their places. Ballplayers know, Brown told Plimpton. And if one of the eleven had been too modest to step forward immediately? The others, Jim said, would have waited for him. The position would have stayed open until he walked in and filled it. Can you imagine any other quarterback, no matter who the guy was, shoving John Unitas aside to get into an All-Star lineup? No, man, no way.

Unless it was Sonny Jurgensen of Washington, sticking a friendly needle in Unitas. Dont you remember, Jurgensen asked a sportswriter not long ago, what I said to him that day we were all together in his restaurant? Remember how he howled? He howled! Of course the sportswriter remembered. The restaurant was the Golden Arm in Baltimore. The fourth man in the booth was a round bartender named Rocky Thornton. Id like to thank you, John, Sonny told Unitas earnestly, for naming the place after me. Not waiting for John to stop laughing, he added, Back when we were playing, I dont remember you being this eloquent with the press. Unitas sipped his beerthe sportswriter had never seen him drink anything except beerand said through that toothy, crooked smile, I always figured being a little dull was part of being a pro. Win or lose, I never walked off a professional football field without first thinking of something boring to say to [Baltimore Sun beat man] Cameron Snyder.

Almost every celebrated athlete has an original story of being burned in print. Johns involved a New York journalist named Leonard Schecter. I was at a golf outing in the early years, Unitas said, an airline junket: American Airlines. After the golf, we were all sitting around the clubhouse, just like we are now. Everybody was drinking. Nobody was taking notes. I said a few things I shouldnt have, questioning Weeb [Baltimore head coach Weeb Ewbank] in a way, contrasting our offensive philosophies. The story came out: What Johnny Unitas would do differently if he were the coach of the Colts. Aint that a kick in the head? The lesson I learned there kept me pretty quiet the rest of my career. If you dont know who youre talking to, you better be careful what you say.

Several years earlier, at his home in Oxford, Ohio, Ewbank told the same story, but better. One of those first off-seasons, he said, John phoned here to say, Weeb, theres a magazine article just out that is going to be very embarrassing to you. A fellow named Schecter wrote it, but it sounds like I wrote it myself. It lists all of the little things Id change if I were the coach instead of you. I want you to know that everything in there is absolutely accurate. Its exactly how I feel. I honestly have no idea how the guy was able to keep it straight. He didnt take a single note. But I also want you to know that I didnt mean for it to be printed. I apologize. Thinking back, Ewbank chuckled and said, Thats Unitas. Punching his visitor in the arm, he said, Nine hundred and ninety-nine players out of a thousand would swear they were misquoted or that what they said had been taken out of context. Not him. It was exactly how he felt. I just said, Forget it, John. Thanks for calling. To tell you the truth, Im not sure if I ever even saw that article.

Through the beery mist of the Golden Arm, the conversation staggered in many different directions until, as usual, it had reeled its way back around to Berry, Gino Marchetti, Jim Mutscheller, Lenny Moore, Jim Parker, Alan the Horse Ameche, Artie Donovan, Bert Rechichar, Bill Pellington, Jimmy Orr, Gene Big Daddy Lipscomb, Alex Captain Who? Hawkins, L. G. Long Gone Dupre, and an era of life and football that was also long gone. If you knew any of us, Jurgensen said for the entire National Football League in the 1950s and 1960s, you knew all of us. Not to contradict Sonny, speaking only for the old Colts, Unitas reworked the sentence slightly. I think you almost had to know all of us to know any of us, he said.

This is a book about all of them, in the pursuit of trying to know one of them, Johnny U. It begins and ends with him. But it is as much about a certain time as a single player. It is less about a specific place in the country than a place where the whole country used to be. Of course, it flies in the face of Plimptons literary maxim that the smaller the ball, the richer the subject. Pro football isnt usually thought of as a romance, but thats the way it is offered here, in black-and-white.

Ours was the great era of professional football, Jurgensen said, because it was the players game then. Its the coaches game now. In those days quarterbacks looked their own guys right in the eye, and then stared across the line at the other guys. Whos ready to do it? Whos starting to quit? We controlled the game. We applied the psychology in the huddle. You know, if in the first or second quarter we found a defensive player we could take advantage of, we didnt always show him up right away.