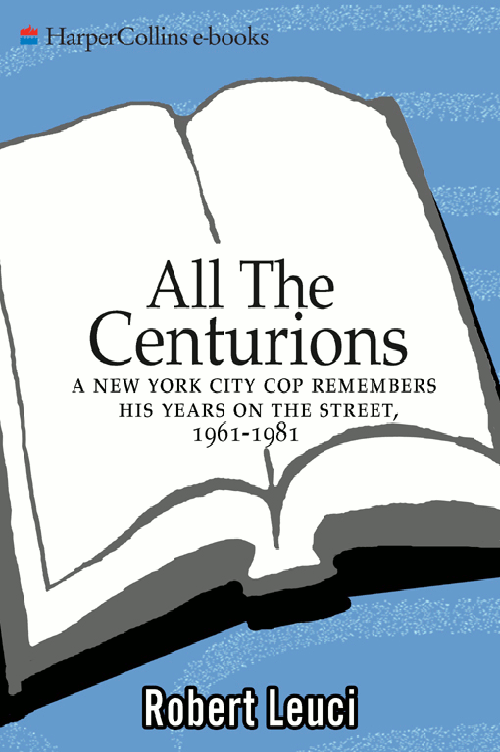

I ts the fall of 1961. Im twenty-one years old and part of a phalanx of gray-uniformed recruits marching into an out-of-date building on Hubert Street in lower Manhattan, the NYPDs police academy. What I remember most are glimpses of things antiquated and worn and the smells, the pleasant aromas of cinnamon and leather that have lingered for more than a hundred years from the lofts nearby that were used as storehouses for bales of spices brought by nineteenth-century sailing ships. I felt the mix of excitement and unnamed anxiety that comes when you are about to enter an unfamiliar world, knowing full well that you are a long way from belonging there. I was at the start of a journey and willing to go wherever the trip took me. Soon enough, mysteries began to slip away and the trip became more important than the destination.

In the academy, time flowed gentlyclass work, the gym, and the pistol range. Every day we took a certain greedy pleasure in knowing more about the life we were going to live than we had the day before; and after a time the weight of a gun belt felt natural.

We recruits got the feeling that there was nothing about police work the instructors didnt know, they were so confident, so sure of their view of the world. Id ask a question and they would stand smirking at me with a fixed serenity. Though I looked for signs of uncertainty, none were there. I marveled at the number of medals they carried on their chests, and how their eyes shone when they repeated over and over, Pay attention here and now or youll pay a price later.

Most of us were in our early twenties, a time for illusions and wild imaginings, when dreams are new, dazzling. I was sure it would last forever; we all were.

As those first days turned to weeks and then to months, I found what I was looking foracceptance, connection, kinshipcall it what you likebelonging just to belong, that kind of thing. It is a very particular sort of yearning, a curious personality trait that has afflicted me my whole life.

You have to learn to compartmentalize your life. You must separate the street world from your world. Do not bring the job home, they told us. When you are all alone on patrol and need help, you will learn to love the sound a siren makes.

THE BABY WAS so small, two or three months old, and it cried a lot. Lover-boy wanted to have sex with the babys mother; he wanted the baby to stop crying. He thought the bottle of sweet wine he gave it would end the crying. The baby went into convulsions, and I didnt have to wonder anymore how Id behave at my first arrest.

It was an old story: a single mother, her baby, and a drunk, horny boyfriend. The first time you see such a thing its a shockthe language, sounds, gestures. The veterans spoke to me slowly, gently, so I would understand that this arrest could turn a long night into an eternity.

I was on a training mission in Harlem. The veterans were telling me, Rookie, heres your first arrest. You want it, you got it. This guys going to be a pain in the ass to collar. Look at him.

We were standing in the kitchen, and cops and ambulance attendants seemed to be everywhere. The mother left with the medical people and the baby. I stared at the boyfriend. He seemed cool, aloof, detached. A small smile, his brains all down in his dick.

That first time and forever after you know youre part of something extraordinary. You begin to gain experiences that give you knowledge and pride. I dont mean all the bullshit macho stuff. Instead its a real sense of accomplishment. Down deep you feel as though youre some kind of hero, the man in the white hat, the marshall of Dodge City.

Youre under arrest, I told him.

He said, For what?

It was a good question. Dont worry, well figure something out, one of the veterans said.

When I tried to handcuff him, lover-boy went off and started throwing punches. He was tough, fast, strong, and a lot more rugged than I thought. There were cops in the apartment, cops waiting in the hallway, cops on the stairway, and they were all getting a laugh at my inability to handcuff this character.

Finally, two or three of them jumped in and gave me a hand; it was over in a flash. A veteran Harlem cop, a huge black guy, grabbed my shoulder.

Kid, he said, this is the street, not the Golden Gloves. Theres no referee out here. Remember, he said, you belong to the biggest, baddest gang in town. You need help, dont waitask.

IN THE DETECTIVES squad room bright and early the following morning, I stood looking at a precinct detective who was wearing brown brogans, black ankle-length socks, a T-shirt, and boxer shorts. He was chomping on a cigar, banging away at his typewriter.

His face was covered with stubble and there were bags under his eyes. He wasnt a bad-looking guy. He did not seem at all happy.

It was early February, a cold and windy morning. I had dressed warmly, way too many layers for that sauna of a squad room.

My prisoner sat in the holding cage across from the detective. His legs and arms were crossed like a Buddhas, his head was down, his eyes at half-mast, all the fight in him gone.

A real pain in the ass, the detective said. When I was printing him, he broke free and tried to dive out the window. Your shit-bird smashed our fucking window. We were freezing in here all night.

The detective told me that he had been forced to spell out to my prisoner why it was a bad idea to break a precinct window on a cold night. Spell out was an interesting way to put it. The prisoner looked as though he had been stunned and then hypnotized.

Your guys wanted in the two-oh [20th Precinct] for an A&R [assault and robbery], he said. You made a good collar.

So what do I do with him?

When you get to court, someone from the two-oh will pick him up and rebook him. Broke our fucking window, this prick.

A sudden change came over the detective; he became affable and friendly, giving me these strange inquiring looks. How the hell old are you?

Twenty-one, I told him. Then he said something I didnt understand.

What? I said.

Nothing personal, but you look like youre in high school. Not old enough to be a cop.

In truth, up until my thirtieth birthday I was carded in New York City. And although that might seem to be a compliment, I never took it that way.

Maybe you should grow a mustache, he told me.

Maybe, I said. Yeah, maybe I will. I knew I couldnt grow a mustache if my life depended on it.

Youd better get going, he said in a helpful tone. The wagon will leave without you.

In those days the department had a small truck they called the wagon that transported newly arrested prisoners. It was green and black with gated doors, no springs, no windows, and wooden benches that were bolted to the floor.