Men-at-Arms 470

Roman Centurions 75331 BC

The Kingdom and the Age of Consuls

Raffaele DAmato Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava

Series editor Martin Windrow

ROMAN CENTURIONS 75331 BC

THE KINGDOM AND THE AGE OF CONSULS

INTRODUCTION

The history and image of the ancient Roman war machine are inextricably linked with the figure of its most famous class of officer the centurio , marked out by the transverse crest ( crista transversa ) on his helmet, the decorated greaves ( ocreae ) protecting his legs, and the Latin vine-staff ( vitis latina ) in his right hand. These men were the true architects of the victories and of the triumphs of the Roman legions, both by the discipline they instilled in their men sometimes with extreme brutality and by the military virtues and exemplary bravery they displayed on campaign and in battle. They created the backbone of professional skills and discipline that made their army the most consistently successful, over the longest period, in history. Although their prestige and importance in ancient times faded later, the officers bearing this rank survived as an institution into the Middle Ages, until the last centuries of the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium.

According to Varro ( DLL , V,16), the most ancient citizenship of Rome from perhaps 625 BC was based on the union of three tribes: the Ramnes, the most ancient, were of Latin origin; the Tities, of Sabine origin; and the Luceres, probably of Etruscan origin. Each of these three tribes was divided into ten politico-administrative communities called curiae (from co-viria , i.e. men together). In case of war, each curia formed something like a levy district, which raised a decuria of cavalrymen (ten men) and a centuria of infantrymen. Theoretically, this word traces its roots to centum , Latin for one hundred, but that connection is now widely disputed. In the Roman infantry, the centuria or century was commanded by a selected officer called a centurio .

THE AGE OF THE KINGS

Centurions in the armies of the first kings

According to Iohannes Lydus ( De Mag. , I, 9), who quotes from the now-lost tactical manual of a certain Paternus, it was Romulus the traditional founder of the city in 753 BC who appointed centurions of the infantry army. There were 3,000 infantrymen armed with shields; he gave to every 100 men a leader, whom the Greeks call hekatontarches and the Romans centurio . Lydus adds that at the time of Romulus there were 30 centurions in the army, and a similar number of manipuli , i.e. units corresponding to 100 men and furnished with standards or signa ( semeiophoroi ). This assertion at least suggests an ancient belief that centurions had existed since the time of the first Roman kings.

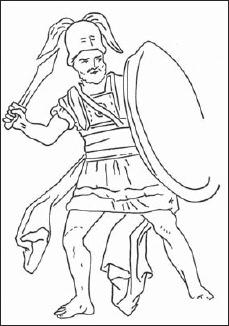

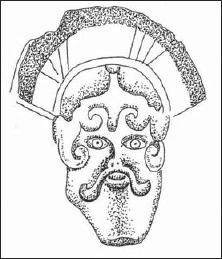

Romano-Etruscan centurion depicted on a 4th3rd century BC cinerary urn from Volterra, present location unknown (compare with ). (Drawing by Andrea Salimbeti, ex-Antonucci)

The second mention of centurions in the Roman army of the first Latin kings is in Livy (I, 28), writing about the aftermath of a battle fought in the first half of the 6th century BC by Servius Tullius against the Veientes and the Fidenates, when the Romans executed the ruler of Alba Longa, Mettius Fufetius, for treacherously abandoning them on the battlefield. The armed centurions received orders from their king to surround the Alban ruler, who was torn apart between two four-horse chariots. The passage attests not only to the existence of these officers in the primitive Roman military organization, but also to the fact that they were directly under the command of the king.

Centurions in the army of Servius Tullius

According to the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, writing in the Augustan period (27 BCAD 14), it was probably the Etruscan king of Rome, Servius Tullius (r. c. 579534 BC), who, when reforming the Roman army in conformity to Etruscan models, promoted the bravest men as commanders of centuriae , i.e. centurions (Greek, lochagoi ). Thus the most famous rank in the Roman army may well have been among the various Etruscan legacies that passed down to the Romans. The Servian reforms developed the centuriae from the Roman tribal system. Livy a contemporary of Dionysius compares the early legion to the Macedonian phalanx (VIII, 8); he also explains the organization of such legions in terms that appear rather up-todate for the 6th century BC. Supposedly, Servius formed 80 centuriae from Roman citizens fit for military service (free-born, without physical disabilities, and honest), and divided such centuriae into two groups: one of seniores or men from 45 to 60 years old, and another one of juniores , aged from 17 to 45. The seniores guarded the city of Rome, while the juniores fought in field campaigns. These 80 centuriae were collectively called the Classis Prima or First Class; the men had to have complete equipment consisting of helmet ( galea ), body armour ( lorica ), round shield ( clipeus ), and greaves ( ocreae ) all made of bronze, and were armed with a spear ( hasta ) and a sword ( gladius ). Two centuriae of fabri or engineers were also attached to this First Class, to handle the war-machines or artillery ( machinae ).

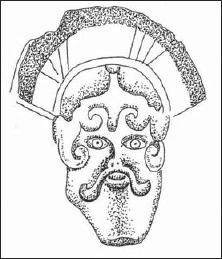

Extraordinary terracotta mask antefissa from an Etruscan temple at Caere (Cerveteri). It shows a kind of masked helmet similar to the original once in the San Marino Archaeological Museum (see ), but furnished with a white crista transversa edged in red. This is evidence that the transverse crest was already in use from at least the 6th century BC. (Drawing by Andrea Salimbeti, ex-Antonucci)

The Classis Secunda , Second Class, was composed of 20 centuriae again divided between juniores and seniores. Their equipment differed from that of the First Class in that they wore no body-armour, and carried not circular bronze shields but the scutum , an elongated shield of wood and leather. The Third Class, Classis Tertia , similarly had 20 centuriae , and the same equipment as the Second Class except for lacking greaves. The Fourth Class, Classis Quarta , was likewise divided into 20 centuriae , but armed with just a spear and a light javelin ( verutum ). The 20 centuriae of the Fifth Class, Classis Quinta , were armed only with slings ( fundae ) and throwing-stones ( lapides ); two of the centuriae in this class were composed of musicians hornblowers ( cornicines ) and trumpeters ( tibicines ).

Dionysius ( Rom ., IV, 1617) gives a slightly different organization. According to him, the Fifth Class was also armed with javelins ( saynia ), and was placed outside the battle-array. Dionysius also writes that Servius Tullius formed four unarmed centuriae ( lochoi ) which followed the armed soldiers. Two of these were composed of armourers ( oplopoioi ), carpenters ( tektonoi ), and those men able to prepare everything needed during wartime (artisans, cheirotechnai ), and were attached to the Second Class, not to the First as Livy stated; the other two comprised trumpeters ( salpistai ) and hornblowers ( bykanistai ), and were also attached to the Second Class, instead of the Fifth Class as according to Livy. These men were assigned according to their age; one of their centuriae followed the seniores , the other the juniores .