Our Little Macedonian Cousin of Long Ago

by

Julia Darrow Cowles

Yesterday's Classics

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Cover and Arrangement 2010 Yesterday's Classics, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

This edition, first published in 2010 by Yesterday's Classics, an imprint of Yesterday's Classics, LLC, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by The Page Company in 1915. This title is available in a print edition (ISBN 978-1-59915-287-5).

Yesterday's Classics, LLC

PO Box 3418

Chapel Hill, NC 27515

Yesterday's Classics

Yesterday's Classics republishes classic books for children from the golden age of children's literature, the era from 1880 to 1920. Many of our titles are offered in high-quality paperback editions, with text cast in modern easy-to-read type for today's readers. The illustrations from the original volumes are included except in those few cases where the quality of the original images is too low to make their reproduction feasible. Unless specified otherwise, color illustrations in the original volumes are rendered in black and white in our print editions.

Preface

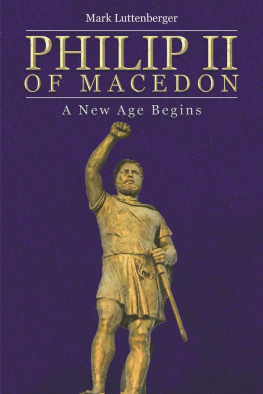

The author of "Our Little Macedonian Cousin of Long Ago," has not attempted to write history in her story. She has sought, rather, to sketch a background of Macedonian lights and shadows, trusting that, when the readers of the story begin their study of the lives of Philip of Macedon and Alexander the Great, the details of literal history mayagainst this backgroundstand out with greater reality.

The typical life of a Macedonian boy attached to the court of Philip, is portrayed, however, in true accord with the spirit and trend of Macedonian history.

Contents

CHAPTER I

Leaving Home

"A RT ready, lad?"

"Yes, father."

" 'Tis time we were on our way."

The young boy addressed turned to his mother and kissed her once more. Then, saying a last farewell to his younger brother and sister, he mounted the horse which stood beside that of his father. Together they rode down the path that led from their home, close to the foothills which surrounded the plain of Macedonia.

If the mother found it hard to see her older son leaving home she showed no sign, but waved a last good-by as he turned at the bend of the path that shut him away from her sight.

Every Macedonian mother of the higher classes looked forward to the time when her son should go to the court of King Philip, at Pella, and there serve as a Page, while being educated for a life of devotion to his country. So the natural sorrow of parting was softened by the honor and advancement awaiting the boy.

"And will I go, too, in a few years?" asked Diades, the younger boy, as they turned back into the house.

"Yes," replied his mother, "you will go, too, when you are as old as Nearchus. Your father is a Companion of the King, you know, and the sons of all the Companions are educated at court."

"When I am as old as Nearchus," repeated Diades. "That will be in three years. Oh, what a long time!"

"Does it seem long?" smiled his mother. "It does not seem long to me," and she drew the little fellow to her in a quick embrace.

"I will stay," cried Ada, running to share the embrace.

"Yes, you will stay and be my companion," said her mother, kissing the rosy, upturned face.

In the meantime Nearchus and his father rode rapidly on. Parmenion looked forward with pride and joy to the moment when he should present his son to the King, Philip of Macedon, and say, "My lord, this is Nearchus, my son. May he serve you well."

Parmenion was proud of his boy, as he had a right to be, for Nearchus was well built, rugged, yet lithe of limb, and with regular features and a clear skin. His life had been free and wild. He had played, as all boys play, at games and sports of various sorts which had developed his muscles and tested his endurance. He had hunted the small animals of the foothills near his home and had bathed in the cold waters of the river.

Of lessons he had had none. Schools were unknown in Macedonia, and except in rare instances the boys who came to the court of the King had had little or nothing of what could be termed an education.

Nearchus' speech was the Macedonian dialect spoken by the common people. His father, Parmenion, spoke Greek, which he had learned at the court of Philip, and Nearchus had picked up a few Greek words. But Parmenion was seldom at home, so he had learned but little from him.

As Nearchus rode on by his father's side, his mind was in a tumult. At last the day had come: the day he had looked forward to ever since he could remember, when he should be taken to court! It seemed strangeyes, and a little hard, toothat he was never to return to his old life of the hills and the plain, for he loved the freedom of it; but a look ahead made him forget all that. He would be a Page of the King. He would wait upon the King, serve him, and be taught the ways of the King's court.

He looked up at his father, and in mind he contrasted him with the rude men of the hill country beyond his home. He was proud of his father; of his manly bearing, his erect carriage, his softly flowing speech, but most of all, of his courage and loyalty to the King.

Then a sudden shyness came over the boy, as he thought of the new companions he was to meet. "I wonder if they will laugh at my rough dialect," he questioned. Then he remembered that they, too, must have spoken the same before they served the King. "And perhaps there will be others just learning," he added to himself, by way of encouragement.

Presently his father turned to him. "You will have many companions at Pella," he said, "and you will not be the elder brother there. You must learn to give and take with the others; be quick and ready in your service to the King; and study your lessons faithfully. Be generous, be true, and be brave, just as you have been at home. Then you will have friends among the boys, and I shall have cause to be proud of you."

"Do you know any of the boys at the court?" asked Nearchus after a pause.

"Not well," replied Parmenion. "But Alexander, the son of Philip, must be close to your age. I trust that you and he may be friends."

Nearchus' cheeks flushed. His father had spoken to him of Alexander before; of the boy's singular beauty, his soldierly bearing, and of his frank and generous nature. Nearchus had thought much about him, for as son of the King he was already a hero in his eyes. In truth, he had dreamed of him more than once, as the time drew near for his own entrance to the court. But never had he dared to think of Alexander as his friend!

When Parmenion looked at Nearchus again there was a deeper flush on the boy's cheeks and a new sparkle in his eyes.

"See," said Parmenion, pointing ahead, as they made a turn in the road, and Nearchus, glancing quickly up, saw at a distance the stone walls which surrounded the city of Pella.

A few moments more and they had entered the gates, and Nearchus looked eagerly about him.

The city was built upon the shore of a sparkling lake, Lake Ludias; and the houses were dotted here and there with little order or regularity, for the streets were little more than winding paths.

Ahead of them rose the great walls of the King's palace, and Nearchus' breath came quickly as he looked at those formidable walls and wondered what the life within them would be.

CHAPTER II

Nearchus Becomes a Page