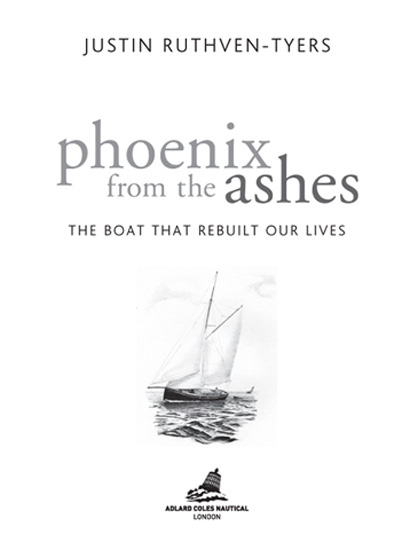

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK TO DAVID SPEARS WHO SELFLESSLY INVESTED IN ME YEARS AGO WITH NO EXPECTATION OF A RETURN ON HIS INVESTMENT AND WHO HASNT BEEN DISAPPOINTED

Contents

Now that I come to think about it, the old stone pier at Carsaig in Argyll, Scotland, was the perfect place for a strange meeting. It is a lonely spot on Scotlands fractured west coast port of arrival for all Atlantic depressions overlooking 4 miles of turbulent sea toward the remote Island of Jura.

The rude pier is a short strip of bumpy concrete splodged out from buckets onto a base of boulders, and is used by two fishermen whose boat leaves at five every winters morning, and returns after dark laden with crimson langoustine known locally as the prawan destined for markets in France and Spain.

We were just setting sail from there in our boat which is also our home when a good-looking, dark-haired man in his late thirties, immaculately dressed in a dark suit and trilby, strode down the pier toward us, his steel Blakeys clacking against the concrete. He looked as though he had come to meet a steamboat, but was 80 years too late. As we swung our bow out to sea the smiling stranger reached the end of the pier and called after us, Ive heard the whole story!

Were it not for the fact that we were the only other people around, we would have assumed that he was calling to someone else. I liked him already but I was so busy wondering, Who on earth is this man why is he dressed like that and what the hell is he talking about?, that I only managed a feeble, How are you doing?

He expanded a little: about the fire and the boatbuilding, and everything And I just wanted to say if ever you write a book about it all, I want the first copy.

This book is for him whoever he was.

***

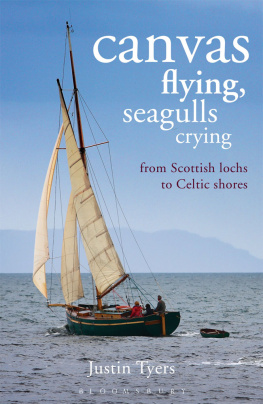

For seven years my wife, Linda, and I lived on board a 15-ton traditional wooden sailing boat, which we built ourselves as complete novices starting with the trees. Shes the prettiest boat youve ever seen.

Our voyages have taken us to Celtic lands to Brittany, Ireland, Scotland, and to our usual over-wintering port in Cornwall, and between those few latitudes we found infinite variety of people and place, and every year we make fresh new travels in those old hunting grounds.

This was our second visit to Scotland in our boat the first had been a summer cruise three years earlier. This was the real thing we planned to find out the hard way if man could survive a Scottish winter, living on a boat. Linda was born in Glasgow and knew better than I did that the days would be short, the nights long, the weather wet, and the temperatures often freezing; and that here on the west coast we would be hounded by storms yet we were attracted by the idea of being cocooned on board our boat in a desolate place. We imagined evenings reading endless books by the cosy glow of our wood-burning stove in the soft yellow paraffin light; listening to gales singing through the rigging. And we imagined days walking the hills; foraging along the low-water shore for mussels and oysters; or searching in the woods for the dry firewood that would keep and cheer us.

We had sailed up from Cornwall on the south-west coast of England to arrive in the boisterous days of summer, when playful winds send white horses racing across the blue water and agitate the emerald pines and the knurled branches of ancient oak.

We had spent months studying the sea charts, pinpointing likely hurricane holes where we could anchor our vessel secure against the winter storms, and began immediately to search out these promising-looking spots. The west coast of Scotland is all rocks a fact that prevents most yachtsmen from the softer south from visiting it at all. Anyone who tells you he has never hit a rock is lying, was our first local report of the kind of sailing we were in for. And we werent long in finding out the dangers for ourselves.

Scudding down the coast off the small island of Kerrera one sunny afternoon, with a gale of wind behind us, and intending to turn sharp left around the heel of the island to enjoy the protected water in its lee, I made the decision to take a shortcut between it and an off-lying rock called Bach Island. There was plenty of room, probably several hundred yards, but I hadnt reckoned on the effect of the shallow water that formed a saddle between the two, or on the increased wind that would be funnelling through. The waves, which had been gently lifting and lowering us as they tumbled ahead, soon became short and steep and took control of the boat. As the stern rose, the bow broached across toward the rocky shore, helped by the press of wind in the huge mainsail, which should have been more deeply reefed; and as the wave passed under us to lift the bow, Caol Ila spun her head the other way, threatening a gybe. The island shore was perilously close, the waves began to break with a roar, and sandy water crashed on deck. I forced the tiller which bent with the strain as far as it would go to one side, and a moment later just as far the other way, trying to maintain a straight course. A minute or so and we cleared the shallows, the waves lengthened, and we were through. It was the closest we had been to wrecking ourselves.

We were looking for places that were interesting, lonely, and beautiful, and would offer us protection from winter storms. Wind will come from all directions, and as it rises in strength, so is there increased danger. A sudden squall will sweep a boat clean off her anchor and onto rocks without warning. And having to move a vessel by night to avoid one danger in the cold, the rain and the dark, where navigational aids are few might lead to another. A good anchorage will offer protection from three of the four points of the compass; in a perfect anchorage, protection from the fourth point will only be a short journey away.

And we wanted comfort, too living aboard doesnt inure you to incessant rolling, to always having to hold on when walking about, to wiping porridge off the walls we wanted to be as still at night as a babe in its cot. In short, we were looking for places to anchor our vessel, here on the wild west coast of Scotland, that never get rougher than a farm pond.

Invariably, such places are difficult of access, being littered with hazards submerged rocks, narrow channels and strong tides; seldom visited during a fine spell of summer weather, they were utterly deserted throughout the winter. Ashore, there may be no house for miles around, but exploring the area often revealed fascinating signs of a more historic habitation a village abandoned in the Highland Clearances, of which only rectangular shapes of tumbled stone remained, with a sheep fank nearby; a graveyard accidentally discovered (hidden amid acres of dense fern, warm, musty, and head-high), with its tombstones carved in bas-relief depicting Celtic warriors dressed in mail, a claymore clasped to the chest and the flat of the blade pressed to the nose, or lichen-covered Celtic crosses unchanged since the days of early Christianity; a standing stone holding its solitary vigil millennia-long; and, on a raised beach where no wave has crashed for ten thousand years, the remains of a lump-rock wall half-concealing the entrance to a cave, a dwelling perhaps of one of the earliest inhabitants hereabouts. Inside the cave, digging at the floor would reveal darkened patches of ground where fires had burned, together with charred hazelnut, limpet shell and bone; and above, the damp rock roof would be discoloured pink-to-purple by heat.

Next page