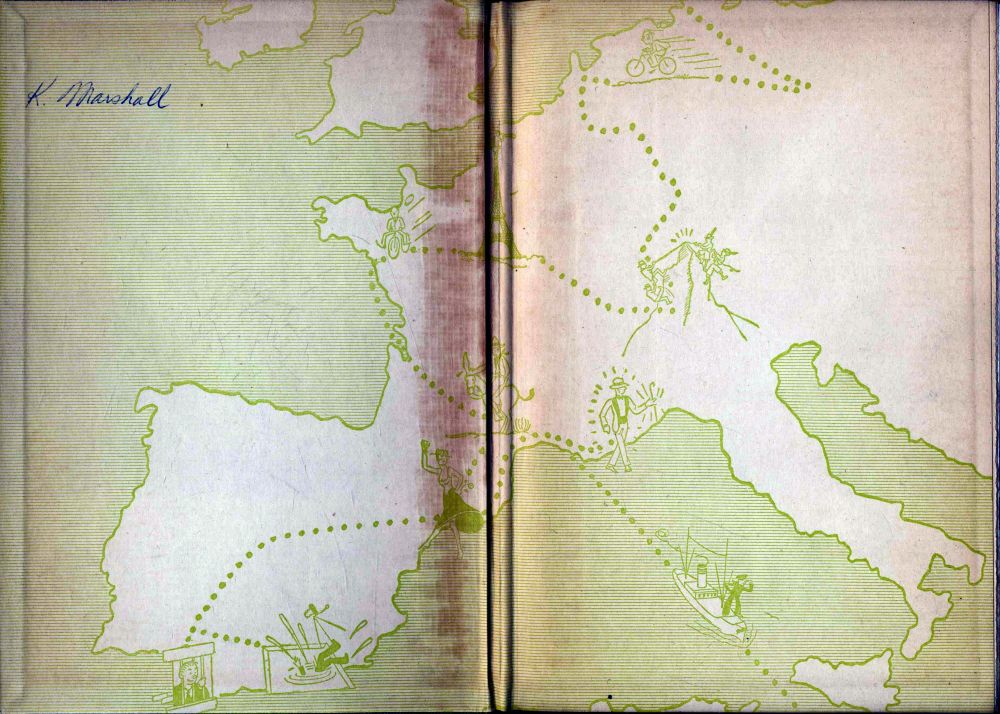

Rear endpaper.

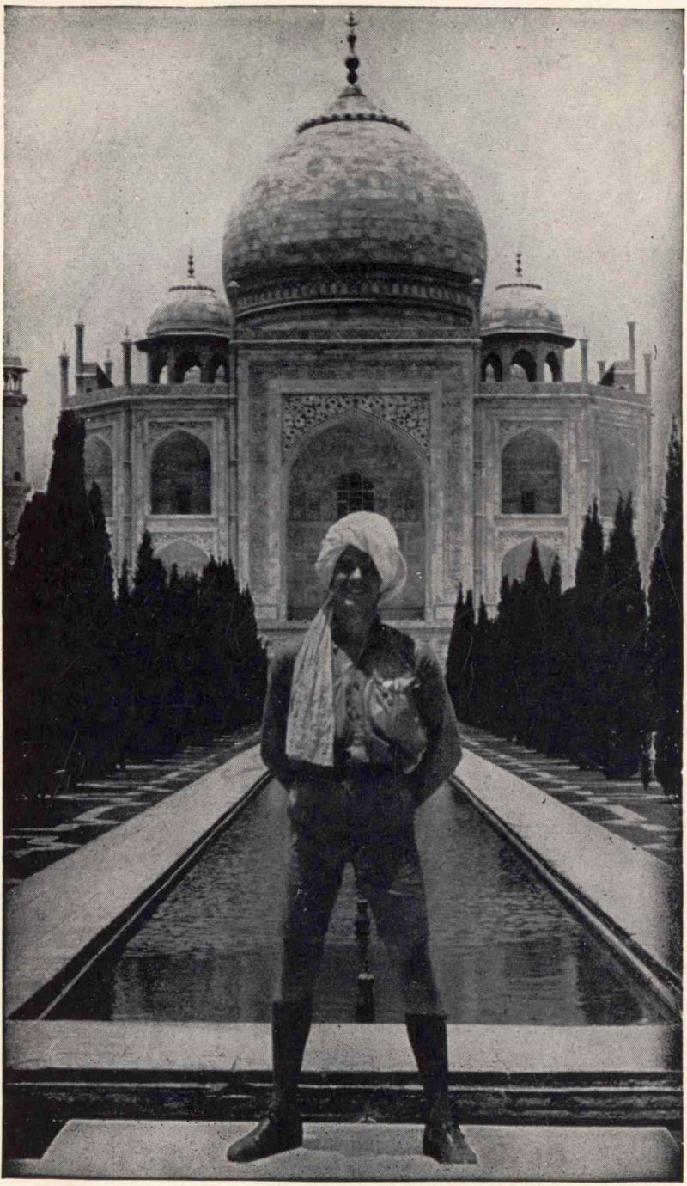

Richard Halliburton before the Taj Mahal.

The Royal Road to Romance

by RICHARD HALLIBURTON

To

Irvine Oty Hockaday

John Henry Leh

Edward Lawrence Keyes

James Penfield Seiberling

Whose sanity, consistency and respectability

as Princeton roommates

drove me to this book

CHAPTER I

THE ROYAL ROAD TO ROMANCE

May had come at last to Princeton. There wasno mistaking it. The breeze rustling through ourwide-flung dormitory windows brought in the freshodors of blossoming apple orchards and the intangiblesweetness of bursting tree and flower. I had notnoticed this fragrance during the day, but now thatnight had come, it filled the air and permeated ourstudy. As I slouched on the window-seat looking outupon the moon-blanched campus, eleven muffledbooms came from the hour bell in Nassau Hall.Eleven oclock!and I had not even begun to readmy economics assignment for to-morrow. I glancedat the heavy text-book in my hand, and swore at theman who wrote it. Economics!how could one beexpected to moil over such dulness when the perfumeand the moon and all the demoralizing lure of a Mayevening were seething in ones brain?

I looked behind me at my four roommates bentover their desks dutifully grubbing their lives away.John frowned into his public accounting book; hewas soon to enter his fathers department store. Penfieldyawned over an essay on corporation finance;he planned to sell bonds. Larry was absorbed inprotoplasms; his was to be a medical career. Irvine(he dreamed sometimes) was struggling unsuccessfullyto keep his mind on constitutional government.What futility it all wasstuffing themselves withprofitless facts and figures, when the vital and thebeautiful things of lifethe moonlight, the appleorchards, the out-of-door sirenswere calling andpleading for recognition.

A rebellion against the prosaic mold into whichall five of us were being poured, rose up inside me.I flung my book away and rushed out of the apartmenton to the throbbing shadowy campus. The lakein the valley, I knew, would be glittering, and Iturned toward it, surging within at the sense of temporaryescape from confinement. Cool and clean,the wind, frolicking down the aisle of trees, tousledmy hair, and set my blood to dancing. Never hadI known a night so overflowing with beauty and withpoetry. The thought of my roommates back in thatpenitentiary room made me shout with impatience.Except Irvine, they were so restrained, so infallible,so super-sane, so utterly indifferent to the divinemadness of the spring moonlight.

All the afternoon of that day I had spent in thewoods beside Stony Brook, lost in a volume of DorianGray . And now as I tramped down-hill to the lake,I began to recite aloud to the trees and the stars,lines from it that had burned themselves into mymemory: Realize your youth while you have it...the sound of my own voice startled me, but thewoods echoed back the phrase approvingly, so I tookcourage. Dont squander the gold of your days,listening to the tedious, or giving your life away tothe ignorant and the common. These are the sicklyaims, the false ideals, of our age.... Sicklyaims, sickly aims, the crickets chirruped after me.Live! Live the wonderful life that is in you. Beafraid of nothing. There is such a little time thatyour youth will lastsuch a little time. The pulseof joy that beats in us at twentyI was already ayear past twentybecomes sluggish. We degenerateinto hideous puppets, haunted by the memory ofthe passions of which we were too much afraid, and theexquisite temptations that we had not the courageto yield to. Youth! Youth! There is absolutelynothing in the world but youth!

A wave of exultation swept over me. Youthnothingelse worth having in the world... and I had youth, the transitory, the fugitive, now , completelyand abundantly. Yet what was I going to dowith it? Certainly not squander its gold on the commonplacequest for riches and respectability, andthen secretly lament the price that had to be paid forthese futile ideals. Let those who wish have theirrespectabilityI wanted freedom, freedom to indulgein whatever caprice struck my fancy, freedomto search in the farthermost corners of the earth forthe beautiful, the joyous and the romantic.

The romantic that was what I wanted. I hungeredfor the romance of the sea, and foreign ports,and foreign smiles. I wanted to follow the prow ofa ship, any ship, and sail away, perhaps to China,perhaps to Spain, perhaps to the South Sea Isles,there to do nothing all day long but lie on a surf-sweptbeach and fling monkeys at the coconuts.

I hungered for the romance of great mountains.From childhood I had dreamed of climbing Fujiyamaand the Matterhorn, and had planned to chargeMount Olympus in order to visit the gods thatdwelled there. I wanted to swim the Hellespontwhere Lord Byron swam, float down the Nile in abutterfly boat, make love to a pale Kashmiri maidenbeside the Shalimar, dance to the castanets ofGranada gipsies, commune in solitude with the moonlitTaj Mahal, hunt tigers in a Bengal jungletryeverything once. I wanted to realize my youth whileI had it, and yield to temptation before increasingyears and responsibilities robbed me of the courage.

June and graduation.... I was at liberty nowto unleash the wild impulses within me, and followwherever the devil led. Away went cap and gown; onwent the overalls; and off to New York I danced,accompanied by roommate Irvine (whom I had persuadedwith little difficulty to betray commerce foradventure), determined to put out to sea as a commonordinary seaman before the mast, to have a conscientious,deliberate fling at all the Romance I haddreamed about as I tramped alone beside LakeCarnegie in the May moonlight.

Our families, thinking it was travel we wanted,offered us a de luxe trip around the world as a graduationpresent. But we had gone abroad that waybefore, and now wanted something less prosaic. Sowe scorned the Olympic and, with only the proceedsfrom the sale of our dormitory room furnishings inour pockets, struck out to look for work on afreighter.

To break into the aristocracy of labor was by nomeans as easy as we had believed. Somewhat to ourdismay we found that wafting Princeton Bachelorof Arts degrees under the noses of deck agents wasnot a very effective way of arousing their interest inour cause. In desperation Irvine and I attempted anew method of attack. We gave each other a soupbowl hair-cut, arrayed ourselves in green flannelshirts, and talking as salty as possible descended uponthe captain of the Ipswich , a small cargo boat,with the story that this was the first time in twenty-oneyears wed ever been on land. The skipper wasa bit suspicious, but our hair-cuts saved the day. Hesigned us onand may as well have since we hada peremptory letter in our pocket from the presidentof the shipping company instructing him to do so.