First published in Great Britain in 2008 by

Pen & Sword Family History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright (c) text Richard Brooks and Matthew Little 2008

Copyright (c) illustrations Royal Marines Museum

ISBN 978 1 84415869 0

Digital Edition ISBN: 978 1 84468 275 1

The right of Richard Brooks and Matthew Little to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Palatino by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

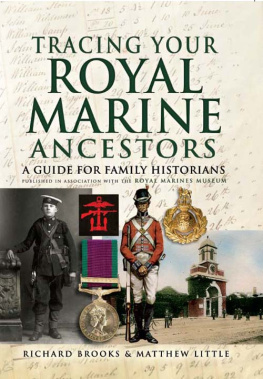

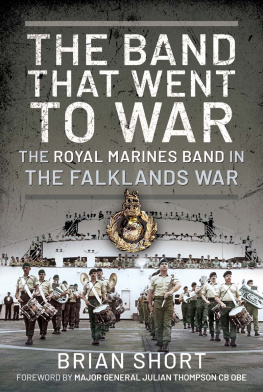

Front Cover, from left to right:

1) Studio photograph of Bugler Sticks Burnett RMLI, HMS Suffolk (19171918)

2) Combined Operations Organization insignia (19421946)

3) General Service Medal (1962) with bar for Radfan campaign (1967)

4) Royal Marine sentinel of 1805 (Charles Stadden)

5) Royal Marine other ranks cap badge 1953 to date

6) Coloured postcard showing Barrack Gate, Forton Barracks, Gosport c.1910

There is no fighting force under the Crown less understood than the marines. Few trouble themselves to know more than that they are useful. Why they exist or why they are useful are not questions which attract attention.

(Army & Navy Gazette 7 February 1874)

PREFACE

T he Royal Marines (RM) are at once one of the most prestigious and most perplexing parts of the Armed Forces of the British Crown. Although clearly soldiers and holding military rank, marines have been part of the Royal Navy (RN) for over 250 years, providing between a tenth and a quarter of its manpower. Tracing descent from the Duke of York and Albanys Maritime Regiment of Foot of 1664, they were disbanded five times before permanent establishment in 1755. Then organized into Grand Divisions wearing red or blue, they are now organized as commandos and mostly wear green, except in the band service. Royal Marines officers appear in both the Army and Navy Lists, and at one time had their own list of officers of the Marine Forces. Not until 1802, however, did they receive the distinction Royal. For over three centuries marines have played an essential part in the Royal Navys most outstanding achievements, from the capture of Gibraltar in 1704 to the final frustration of French invasion plans at Trafalgar (when a Royal Marine sergeant helped carry the dying Nelson below), to the reconquest of the Falkland Islands in 1982.

The existence of a single unified body of marines is of more than incidental interest to the family historian. The large numbers of men serving as marines at different times makes the Corps a statistically more significant source of military ancestors than any infantry or cavalry regiment. Except during the wartime emergencies of 191418 and 193945, army regiments never exceeded a couple of thousand men apiece. Marine strength, by contrast, hovered between 10,000 and 20,000 throughout the nineteenth century, with far higher numbers in wartime. Despite the Cold War peace dividend, there are still over 6,000 Royal Marines. Besides their numbers the interior economy of the marines as established in 1755 also made them more likely to appear in a family tree. Regular stays at divisional headquarters between periods at sea encouraged long-term relationships, denied to soldiers shipped overseas, for seven or twelve years at a time. Marines were family men, and their sons followed them into the Corps, inspiring the claim that they dont recruit marines, they breed em.

The position of these soldiers at sea has not always been easy to comprehend. Sir John Colomb, a Royal Marine Artillery (RMA) officer and Member of Parliament, described his old Corps in the 1880s as presenting a picture of confused anomalies and inconsistencies. You see, chum, said Private Henry Derry, a veteran of the 1840s and50s, I cant separate we Joeys from the Jacks, nor the Jacks from we Joeys, so we get lost. Naval officers took advantage of the confusion to steal the limelight:THE LAURELS WHICH YOU WIN, wrote an irate subaltern of the 1780s, OTHERS WEAR. Historians have contributed towards the invisibility of the Corps. Christopher Lloyds The British Seaman has a single index entry for marines, as if the story of the lower deck can be told without discussing the interaction between sailors and marines. John Keegans Battle at Sea has none at all, despite the red jackets on its cover.

The sources available to family historians seeking a marine ancestor reflect the anomalous position of the Marine Corps within, but not of, the Royal Navy. Its possession since the mid-eighteenth century, of fixed headquarters in the navys home ports at Chatham, Portsmouth and Plymouth has encouraged the survival of numerous classes of records. Army regiments had no fixed homes until the later 1800s. The routine of marine barrack life inspired the keeping of domestic records such as divisional registers of births, marriages and deaths. The monotony of service at sea encouraged officers and marines to keep personal diaries and notebooks, examples of which still find their way to the Royal Marines Museum.

This wealth of material is balanced by corresponding gaps. The nature of their service posed peculiar threats to the survival of marine records. HMS Chichesters returns for FebruaryJuly 1707 went down off the Scilly Isles with Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell. More banal accidents have taken their toll. Major Thomas Wybourne RM lost four volumes of his journal in the post. None of the surviving documents was kept for the benefit of genealogists. Colonel Loureno Edye, the great historian of early marines, lamented the deficiencies of seventeenth-century records, which are either mutilated by the ravages of time or are deficient in the very essentials which render them so interesting to the modern student. Divisional officers and Admiralty clerks would have been astonished to learn that anyone would ever look at their letters and returns again. Not only are official documents organized in an unhelpful manner, they are incomplete. The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were richly documented, a situation since threatened by wartime economy paper, unstable electronic records and record retention policies driven by accountants rather than archivists.

The chronological and geographical spread of the services of the Royal Marines present particular difficulties for the researcher. The Globe & Laurel, the Corps journal and a prime reference for family historians, once commented, the story of the marines from beginning to end must approximate to a history of the British at war. This work, therefore, avoids detailed analyzes available records, explaining how to use them to trace the career of an individual marine. Researchers with a specific enquiry, for example concerning attestations, may go direct to the appropriate section of that chapter. Those requiring further information about particular aspects of Royal Marine history should consult the general histories in the Further Reading section and their bibliographies.

Next page