Introduction

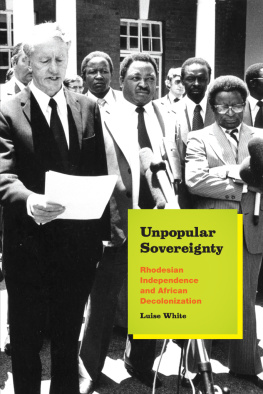

There is a wilderness embedded in my heart and etched on my soul. It is deeply imprinted on my childhood like ragged erosion scars the landscape. It is the taste of ripe mango juice running down my chin. It is the scent of dust and rain. It is the dull shine of a rifle in the bedroom corner. It is mud pies and mulberry-stained feet. It is a story of ears and lips cut off. It is newspaper headlines of missionaries murdered and terrorists slaughtering farmers. It is a song of patriotism howled with futility into the wind. It is the Boogeymans face at the window. It is exhilaration and despair. It is lost innocence and the burying of a dream in a shallow grave. It is a place that is no longer written on any map.

Rhodesia.

It is the place that raised me strong-willed, fearless, curious, racist and entitled.

My heritage and its bloodied, soiled history thats entwined around my heart courses through my veins, pulsating with a mixture of pride and shame.

I am White. I am African. I am a descendant of White settlers, of tearoom owners, of tobacco farmers, of copper and asbestos miners, of British Military, explorers, exploiters and cricket players. I am English-speaking but not actually English. My Britishness is second-hand, passed down like ill-fitting clothes, worn by others before me with stains that cannot be bleached out or stitched over with a patch.

White.

British.

African.

Half of each and none of all. A cultural half-breed.

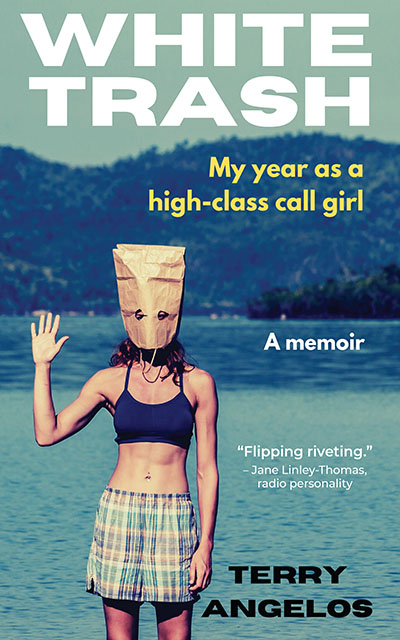

I have impeccable manners. I am intelligent, bright and accomplished. Despite this, I have taken more than a few wrong turns, wandered off track and gotten lost down many dark rabbit holes. My recklessness, poor choices and lack of boundaries cannot be traced to the usual broken home, child abuse, abandonment, desperate poverty or drug addiction syndrome. That would offer a plausible explanation. You could put me in a cardboard box marked defective, or most likely to make a string of poor choices. You could feel pity for me.

No, I am the first daughter of two devoted parents. Respectable, middle-class teachers. From the outset, I was destined for success in a white-picket-fence, 2.5-children family. A photograph my Catholic mother could be proud of.

Instead, by the time I reached 20, I had become a call girl. It was not forced upon me. I was not the victim of human trafficking or in a situation that gave me no other choice or nowhere to turn. I went in with eyes wide open, alert, aware and deliberate, with no one to point any fingers at.

There must be something or someone to blame? Surely something dragged me down the slippery slope into Londons underground sex world? What was the catalyst to my aberrant behaviour? Why do I always take things too far? Why have I always pushed the boundaries? Why am I so reckless and unguarded? My appetite for life is relentless, obsessive, greedy, compulsive and dangerous. Curiosity killed the kitty. Its also what nearly killed me.

Its taken 32 years to feel ready to write down my story, to unravel a bulging mass of muddled threads, like one of those childhood maze puzzles. Help Terry find her way out with a crayon. I never could find my way out. Instead, every twisted path led me to the edge of the abyss. The threads are memory scabs that I scratch till they bleed, shards picked from my brain and bones, caught in my throat, dislodged and examined. This is my search to understand me, the origins of my deviance, and the ingredients that created my recipe for disaster and redemption. This is the story of how I finally managed to uncover myself.

Chapter 1

Maggie

My earliest memory is a secret. It is the first time that I go to a place I am not supposed to go to and do something that I shouldnt.

I am a scrappy four-year-old when I wander away from our house. My mother is distracted with the frazzling demands of my new and unwelcome baby sister. She is always crying, her tiny face red and angry, little fists clenched. She already behaves like the middle child that she will one day become.

The heat of the day has simmered off as it turns to dusk. I crunch along the gravel driveway, following the swaying hips of Maggie to her khaya. I am unaware that I am crossing the lines of segregated living and separate eating utensils.

Maggies khaya is a small cement block room with a tin roof at the bottom of our garden. Its called the servants quarters, as if we are the Lords of a grand manor in our little red-brick house.

Her single iron bed is raised off the ground by several bricks. On my tiptoes, I can almost see the worn blankets and dent left by the memory of her body. The bed is raised as a precaution against the advances of the Tokoloshe, the African spirit demon known to have his way with women and bring a myriad of illnesses, bad luck and even death.

There is a small table in the tiny room, covered with newspaper and a few necessities like tea, jam, salt. I sit on the cool concrete floor in front of the gas cooker, crossed-legged like a skinny Buddha. The quietness of the small room feels secret and sacred. Maggie leans over the pot of maize sadza and gravy made from bitter, salty greens like spinach. She smells of Sunlight soap and her warm musky odour mingles with the cooking smells. It feels deliciously naughty to sit on the floor and eat with my fingers like she does. I watch how she rolls sadza into a ball with her fingers and dips it into the gravy. I copy her, eager to show her that I can also roll sadza and soak up the gravy .

Sometimes we have tea and thick slices of bread my dad calls doorstops. We mix cement, taking a bite of bread and gulping a mouthful of sweet tea to mix with the bread in our mouth. This is bad table manners. This is how the Africans eat. Dont eat like that, its disgusting, my mother would say if she could see me now. I am not supposed to mix cement or eat doorstops like an African. But she cant see me, so I mix cement with Maggie, feeling happy as a pig in mud.

The light dims as the sun slips away, leaving flames dancing on the smokey walls. It feels like another home and Maggie feels like another mother. In these precious moments she is all mine and I have no comprehension that she has any other children, family or life outside our home and her khaya.

When my tummy is full as a fat tick, Maggie says, Hamba, shaya wena, and I run home with no appetite for Shepherds Pie or Eggy Soldiers.

It is the 1970s and generally, children should be seen and not heard. Dr Spock is instructing parents on how to raise their offspring by trusting their instincts and being flexible with routine. He is vilified as the founder of the permissive parenting style of Baby Boomers.

I play outside, mostly unsupervised in the daytime, happy to ramble around barefoot. Children roam around our neighbourhood, knotted together in little gangs. There is no need to worry, we are safe in the perimeters of our White community.

My mom says, Come home when it gets dark. I always wander off. I am not the child that follows her mother around whining and complaining of boredom. I dont tug at her skirt or latch onto her. There is too much to do, to create and discover. My imagination is bright and vivid. It is like a kaleidoscope. Every time I blink, vibrant colours, ideas and wild images burst into my head. I am always exploring, building cities in dirt, climbing magical trees, making forts with sticks and straw. I play with dolls who for some reason are always dying of terminal and frightful illnesses.