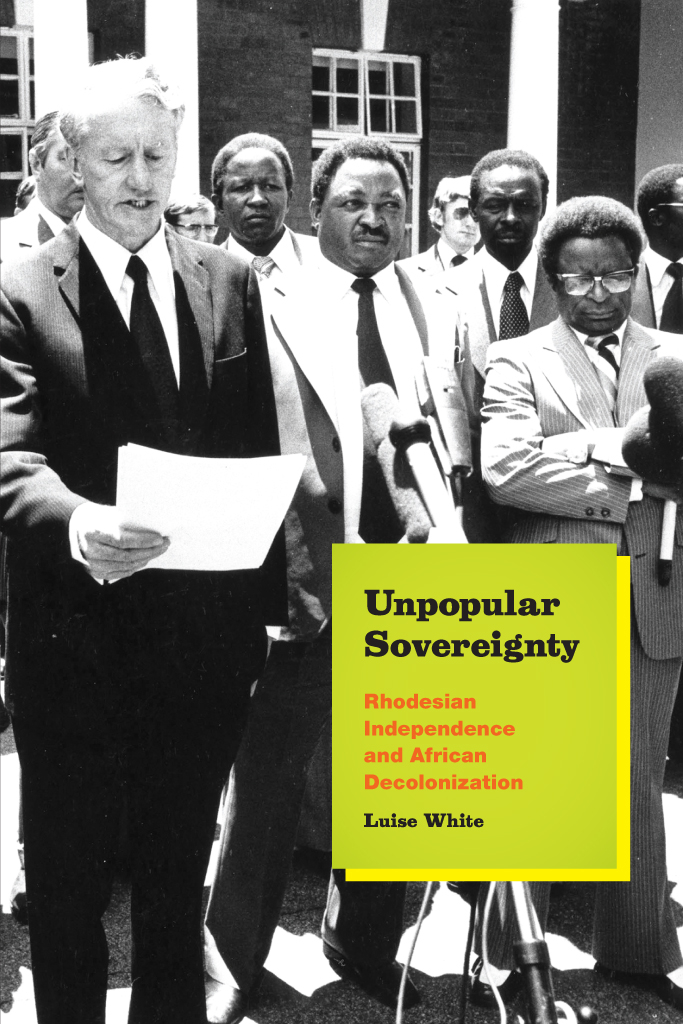

Unpopular Sovereignty

Rhodesian Independence and African Decolonization

LUISE WHITE

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

LUISE WHITE is professor of history at the University of Florida. She is the author of four books, including The Comforts of Home: Prostitution in Colonial Nairobi, also published by the University of Chicago Press.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23505-9 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23519-6 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23522-6 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226235226.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Luise, author.

Unpopular sovereignty : Rhodesian independence and African decolonization / Luise White.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-23505-9 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-226-23519-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0226-23522-6 (e-book) 1. ZimbabweHistory19651980. 2. ZimbabweHistoryAutonomy and independence movements. 3. DecolonizationZimbabwe. 4. ZimbabweHistory18901965. I. Title.

DT2981.W45 2015

968.91'04dc23

2014030670

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

I rst went to Zimbabwe with a project in medical history, but even as I prepared to do that research I found myself drawn to the sheer amount of white writingmemoirs and novels and polemicswritten about Rhodesias renegade independence during it and after Rhodesia ceased to exist. As the medical history project became increasingly untenable, I thought I would write a book about Rhodesian independence based on these published materials. What made me think more critically about what such a project might entail and what I might nd in archives and libraries were the conversations I had when I was a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in 19971998. James Hevia, Douglas Howland, and David Gilmartin demonstrated by example the imaginative potential of political history. This encounter with scholars of East and South Asia convinced me that what was at stake in this project could not be expressed in the binary of published versus unpublished or even primary versus secondary sources. Doug Howland in particular encouraged me to rethink how I read texts and also to attend to the genealogies of language in which the historical experience of power and privilege was recorded. For the next decade, however, I imagined I could write a history of Rhodesian independence without addressing the complications of the ve constitutions Rhodesia had between 1961 and 1980. I had hoped to write a book without learning the minutiae of voter qualications, the question of dual voters rolls, and the byzantine rules for cross-voting. At the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies at Princeton University in 2007 I had the time and the library resources to read franchise commissions and constitutions. To my surprise I discovered that the minutiae of voter qualications were a way to talk about history and difference at the end of the colonial era; separate voters rolls for Africans and Europeans were a late colonial ction about ending racial politics; cross-voting was a territorial mechanism for keeping racial politics buoyant. The organization of this book emerged out of that fellowship, and I am grateful to Michael Gordin and Gyan Prakash for their support.

I was able to explore the overlapping histories of states and votes and voters in three conferences. The Center for Twenty-First Century Studies at the University of WisconsinMilwaukee funded Doug Howland and me to organize a conference historicizing sovereignty. At the University of Florida, the Center for the Humanities and Public Sphere funded two workshops, one on decolonization and the franchise and one co-organized with my colleague Alioune Sow on the production of memoirs in Africa since 1980. I am grateful to the participants for their papers and discussion. This research was funded by the Social Science Research Council, the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies. The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation allowed me the time to write this book. Such a list masks the colleagues who have, time after time, written the letters that recommended me for funding. Over many years and no small amount of disk space, Fred Cooper and Ivan Karp have supported me and my research in ways I can only call unfailing. Ivan did not live to see this book. He never really approved of this project, but his belief that a scholars engagement could trump his own sensibilities has served as an example of uncompromising professionalism and is one of the many reasons he is so sorely missed.

This book was written at the University of Florida, where the Department of History has supported my work and helped me secure funds for research from the College of Liberal Arts for research trips. At Florida I am afliated with a Title VI Center for African Studies. Title VI centers are relics of the Cold War, to be sure, but like relics of old they have been given a special and somewhat different meaning by the people who revere them. At Florida this has meant a sense of place and possible futures for Africa shared by a truly interdisciplinary group of scholars. The centers directors and associate directorMichael Chege, Abe Goldman, Todd Leedy, and especially Leonardo Villalnhave been only too eager to turn scholars ideas into research trips and conferences and invited speakers. Steve Davis began graduate work in African history at Florida in 2003, when I had just begun to think seriously about this book. He nished his dissertation years before I nished this manuscript, but not before I learned an enormous amount from him.

Writing about the history of a state that no longer exists has required a triangulation of archives and libraries. I have been helped along this circuitous path by Ivan Murambiwa at the National Archives of Zimbabwe, Shirley Kabwato at the Cory Library at Rhodes University, John Pinfold at Rhodes House in Oxford, Hilary McEwan at the Commonwealth Secretariat in London, Chris Webb at the Borthwick Historical Institute in York, Marja Hinfelaar at the National Archives of Zambia, and Kelebogile Pinkie at the Botswana National Archives. In the United States I am grateful for the assistance of Jennifer Cuttleback at the LBJ Archives in Austin, William McNitt at the Gerald Ford Library in Ann Arbor, Carol Leaderham at the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford University, David Easterbrook at Northwestern University, Dorothy Woodson of the Sterling Library at Yale University, and most of all, Dan Reboussin at the University of Florida.

My research outside the United States would not have been possible without the friendship and hospitality of Irene Staunton and Murray McCarthy in Harare, Helen and Robert Irwin in London, Judy Butterman and Roger Tangri in Gaborone, Megan Vaughan in Oxford, Diana Jeater in Wick, Bill Freund in Durban, and Isabel Hofmeyr, Jon Hyslop, and David Moore in Johannesburg. Colleagues, journalists, former Commonwealth ofcials and Rhodesian ofcials in Zimbabwe, and those in what Zimbabweans call the diaspora have been exceptionally generous with their time and insight. Many asked not to be cited by name, and so I refer to these conversations as my eld notes. I want to thank the named and unnamedfriends and informants and participants in various seminars in various countriesfor their comments and suggestions.