To Janet, my loyal and constant and compassionate supporter and companion during the turbulent decades of my political life. She was tireless in her work of researching history and facts, and editing and bringing some order to my writings, which were often erratic and disjointed because of my numerous other commitments.

My gratitude to her is eternal and unwavering.

Contents

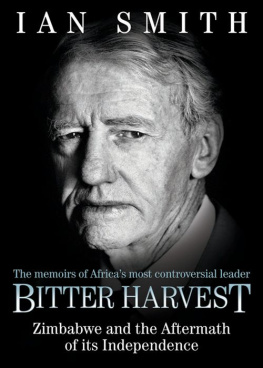

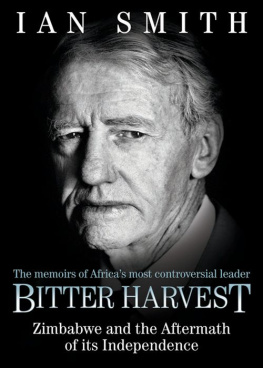

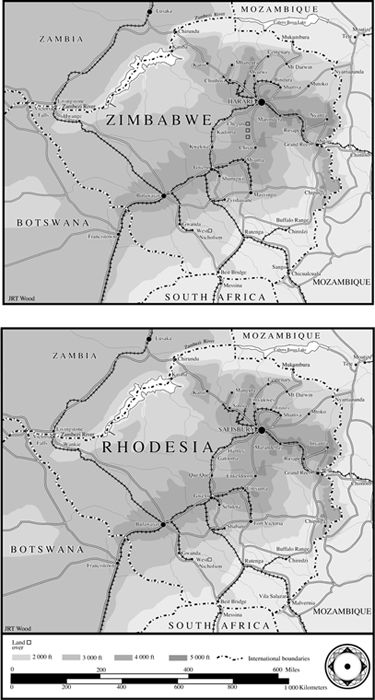

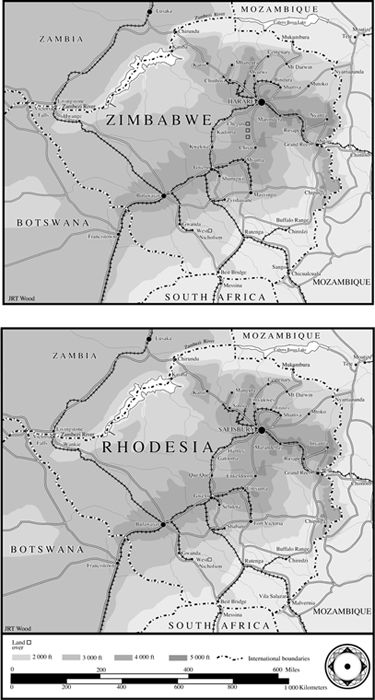

I an Douglas Smith died on 20 November 2007, a few months short of his 89th birthday. For 15 years, between 1964 and 1979, he had been prime minister of Rhodesia, the last but one country in southern Africa to be governed by whites, once called Southern Rhodesia and today known as Zimbabwe.

In the great drama of the 20th century decolonisation of Africa, he will perhaps be seen in future as little more than a footnote, a Canute who declared unilateral independence in a futile attempt to resist the tide of black rule sweeping across the continent. Had he never existed, the history of his stunningly beautiful native land would probably have been much the same.

But for a decade and half, Smith held British and international diplomacy to ransom. Vilified by many, lionised by a few, he became a household name around the world. Then Rhodesia vanished. Had independent Zimbabwe flourished, or merely avoided the shambles of today, there would be little more to say. Instead it has experienced one of the most devastating collapses on a continent that has tasted more than its share of them. A country that set out life as a jewel of post-colonial Africa has become a basket case, a nightmarish kleptocracy sustained by violence, corruption and reverse racism, its every failing blamed by President Robert Mugabe on a plot orchestrated by the countrys remaining whites and by the old colonial power in London to overthrow his rule.

History rewrites reputations, and the plight of Zimbabwe after 28 years of Mugabes rule is forcing a second look at the reputation of Ian Smith. The depth of the crisis has surpassed even his own bleakest warnings and questions most of us would prefer not to ask must be asked. Was he right all along, with his prophesy that black rule would be a disaster? Which leads to an even more unmentionable thought: might it have been better for Zimbabwe and Africa to have remained under white rule?

Ian Smiths background was quintessentially colonial. His father Jock had emigrated from Scotland to Rhodesia in 1898, eight years after the first pioneer column despatched by Cecil Rhodes British South Africa Company crossed the Limpopo river modern Zimbabwes border with South Africa to explore and exploit the rich virgin lands that lay beyond.

The Smiths settled in Selukwe, 200 miles south of the capital Salisbury, now Harare. There Jock ran a farm and a mine, chaired the local cricket and rugby clubs and bred racehorses. Their son Ian, born in 1918, followed in his footsteps. He was an undistinguished student, but like his father (and most white Rhodesians for that matter) a passionate sportsman and lover of the outdoor life. A self-described African of British stock, Smith symbolised a society that considered itself more British than the British, and behaved as such. He believed in the old country, in the British Empire, and in the Empires civilizing mission.

When conflict loomed in Europe in 1939, the adventurous and patriotic young man trained as a pilot, before serving in the Rhodesian air force, and then in Spitfire Squadron 130 in the Royal Air Force. His war took him to Persia, the Middle East and finally Europe where he was shot down over Italy in 1944 and spent five months with the partisans behind German lines.

This gallant war record vastly complicated British attitudes to Smith during the crisis over Rhodesian independence two decades later. Many of a certain generation could not understand why Good Old Smithy and Plucky Little Rhodesia were held in such official disapproval. Yes, he led a white minority government that in 1965 had the temerity to declare independence. But he might have come from the home counties though he had done more to defeat Hitler than the majority of British citizens. Beyond argument moreover he was extremely brave.

It is thus hardly surprising he enjoyed unwavering support from elements of the British Conservative party and of the conservative press. He also knew exactly how to appeal to British nostalgia, an especially potent emotion during the 1960s and 1970s, as the countrys global influence declined, amid a succession of sterling crises and withdrawal from an empire that could no longer be afforded. If Churchill were alive today, Smith said soon after UDI, I believe hed probably emigrate to Rhodesia because I believe all those admirable qualities and characteristics of the British we believed in, loved and preached to our children no longer exist in Britain. In golf clubs and saloon bars across the old country, countless Britons undoubtedly agreed with him.

Had his father left Scotland and settled in Australia, Canada, or New Zealand, the world would have been no problem with a Prime Minister Ian Smith. Instead Jock chose Rhodesia, whose ambiguous initial status was largely responsible for the difficulties later on. Rhodesia was not a typical African colony, ruled directly from Whitehall. It was founded by Rhodes under a charter extended to his company. From the start it was a sub-contracted or, to use the modern term, outsourced form of empire.

Unlike Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, and Nyasaland, now Malawi, Southern Rhodesias two partners in the short lived Central African Federation, few if any British administrators lived there. From 1923, it enjoyed quasi-dominion status, for all practical purposes run by the local white minority which liked to think of itself as no less African than the black majority it ruled. But unlike Australia, New Zealand and Canada, Southern Rhodesias whites were outnumbered 20 to 1 by the native population. And when the crisis broke, Britain would find itself in the uncomfortable position of having responsibility without the power to go with it.

Smiths political career had begun in 1948 when he was persuaded to stand for Parliament for the Liberal Party. In the elections that September 16, the Liberals lost six of their previous 11 seats, but not Selukwe where Smith was standing. Thereafter events moved fast.

Self-governing on almost all domestic matters, white Rhodesians were already pressing for nationhood. Britain established the Federation in 1953 as a half-way house, but the unnatural entity was soon strained to breaking point by growing demands by the black majorities in Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia for full independence. In the outside world too, circumstances were changing rapidly. Addressing the South African parliament in February 1960, Harold MacMillan evoked the wind of change blowing through Africa, while the US, Britains most important ally, was also pressing for de-colonisation.

In 1963 the Federation collapsed. Majority black rule however was not what Southern Rhodesias whites had in mind. In Salisbury the Rhodesia front, a new white nationalist party of which Smith was deputy leader, won power. Within a year Winston Field the prime minister was voted out of office by his parliamentary colleagues who deemed him too moderate. He was replaced by Smith, with a mandate to go for independence. Six months later Harold Wilsons Labour Party won the general election in Britain, and the stage was set for showdown, between the de facto colonial power committed to black majority rule and the white settlers who had taken over an African land.

Next page