Description

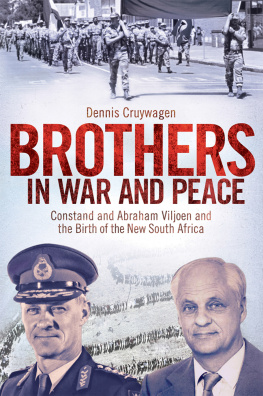

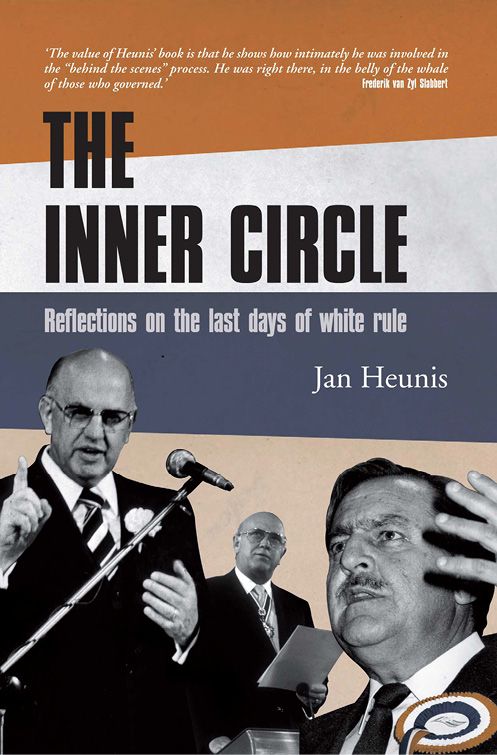

In The Inner Circle , Jan Heunis reflects on the twilight years of white rule in South Africa through incisive portraits of key individuals, such as Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, PW Botha, Hernus Kriel, Kobie Coetsee, Dennis Worrall and Roelf Meyer, as well as accounts of events such as the signing of the Nkomati Accord, PW Bothas Rubicon speech and the CODESA negotiations. He reveals many behind-the-scenes stories, both professional and personal, and describes how the National Party was eventually outmanoeuvred in negotiations with the ANC as South Africa emerged from the darkness of half a century of Nationalist rule. The son of National Party politician and Cabinet minister Chris Heunis, Jan Heunis was not himself a politician, but his position as Chief State Law Adviser in the State Presidents Office under PW Botha gave him a unique insight into the events of the period. He later played an influential role in the multi-party negotiations that led to the Constitution of 1996.

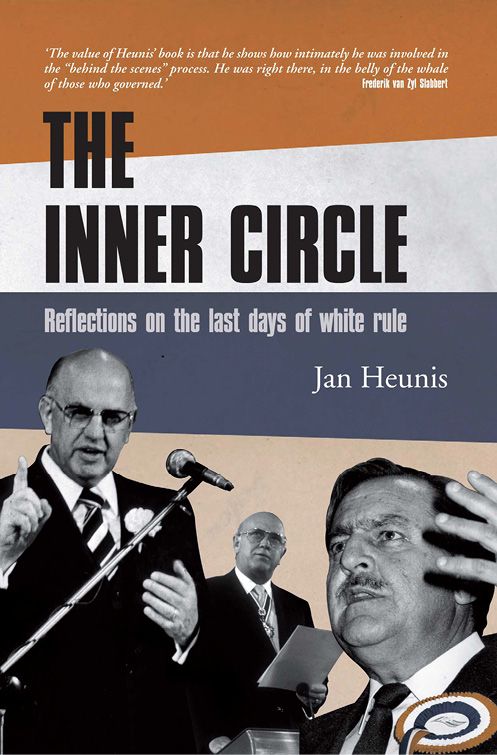

Title page

THE INNER CIRCLE

Reflections on the last days of white rule

JAN HEUNIS

JONATHAN BALL PUBLISHERS

JOHANNESBURG & CAPE TOWN

Dedication

In memory of my friend, Eljho, and my father, Chris, who died, in that order, the one shortly after the other, while I was writing this book.

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Towards the end of 2005 I visited friends of mine, Mike and Eljho, at Kleinbaai on the south-east coast. I started dictating this little book on my way there, and also while driving between work and my home in the mornings and in the evenings.

It progressed well until Eljho died on 15 December 2005. Shortly thereafter, during January 2006, my father also died. For a long time I stopped dictating, but was encouraged to continue by Frederik van Zyl Slabberts book, The Other Side of History . In a very real sense his book inspired me to go back to work on mine.

I would not want this book to be perceived as a self-righteous condemnation of other people. So let me say it: I have many shortcomings. Probably more than many. I would like to believe, however, that I have sinned more frequently and more seriously against my conscience than against other people. My father would have said, in his inimitable way: With all piety, it is safer to sin against God than against men.

I grew up in a house in a cul-de-sac at the edge of the forest in George South. The forest effectively divided the town in two parts. The first part of my conscious life was about missing my father, a busy young attorney and community person. I got many expensive gifts from him, such as had seldom been seen in a small town like George. He had a small yacht built for me, gave me a tricycle with a little bakkie, also specially built for me, a bicycle much too large for me, a scooter with air-filled wheels, and a weird-looking three-wheeled whatever. I gave virtually all these things to the children of Standers-gang, very poor people who lived a block or two away from where I lived. I remember at least one occasion when my mother went to retrieve some of these gifts. I suppose I got all these fancy presents because my father felt that he had to compensate for his absence.

To me my father was something of a demi-god whom I desperately missed. Our house was opposite what is known as a meent , the common, as large as four rugby fields. I remember one day I called out to my father when he arrived home from work (accompanied by a friend, colleague or whatever). I was desperate for him to watch me kick and catch up-and-unders. After many sessions of practice on the meent I was near perfect at it. Predictably I did not catch the ball this time. I so much wanted him to watch my second effort, but he did not.

Equally predictably I made a similar hash during the only rugby game I played in that my father came to watch.

At the time I revelled in the adoration of my grandmother on my fathers side. She was deeply involved in charity work, and my generosity made us allies. She unashamedly called me Jan number one, and made no bones about the fact that I was her favourite grandson. Small wonder that the others gave me such a hard time on our meent .

When I was young, I was blissfully unaware of the fact that my father, who was involved with the activities of many organs of civil society, was also the member of the provincial council for the constituency of George. PW Botha was the member of parliament. I was rudely confronted with this reality when my standard two teacher, a particularly nasty piece of work, told me out of the blue that I should not think that I was special because my father was the local MPC. I had no idea what he was talking about.

By reason of his membership of the Cape Provincial Council, my father had to attend sessions of that Council in Cape Town from time to time. One Sunday afternoon during the school holiday, shortly before he was due to leave for Cape Town for one such session, I hid in the car in a futile attempt to go with him. Predictably I was seen and told to get out of the car.

I went to sit and sulk in the lounge where my mother found me and told me to go and get ready because my father was coming to pick me up. I actually went with him to Cape Town for the week.

When I was 13, my father became a member of the executive committee of the Cape Provincial Council, as a result of which the family had to move to Cape Town.

Thus we went to live in an official residence in Newlands, and I started attending the Groote Schuur High School at the commencement of the second term of my standard seven year. I saw even less of my father, since he travelled to George and back every weekend (on one occasion three times during a single weekend) to be in his constituency.

I was desperately unhappy in the new school, and missed my friends in George and the forest in which I used to play for many hours of the day, frequently by myself.

Despite being extremely unhappy, however, I was, for some reason, voted head boy of the school as well as the pupil who meant the most for other pupils, in my matric year.

To all intents and purposes I left home at the end of matric. After doing my military service, I enrolled for a law degree at the University of Stellenbosch. During weekends I would almost invariably go to George. In the beginning I hiked, and later I used my own car, a Volkswagen 1200.

At Stellenbosch I immediately became involved in student politics. Since Piet Vorster and I were classmates and shared an interest in politics, I got to know his father, Prime Minister John Vorster. On a personal level, I found him to be a very likeable person.

During my university vacations I worked as a reporter at a local newspaper in George called the George & Knysna Herald . During this time, the first half of the seventies, I became good friends with Martin Botha, an excellent chef and a so-called Coloured. I attended his wedding in the Coloured township of Pacaltsdorp, and proposed a toast to the bridal couple. The following week, this was prominently reported in the George & Knysna Herald s main competitor, the Het Suidwestern , under a headline to the effect that Chris Heuniss son had attended a Coloured wedding. By that time my father had become a minister in John Vorsters cabinet, and the fact that I attended the wedding was considered newsworthy!

On leaving the university, I joined the Department of Foreign Affairs as a law adviser, and subsequently became Chief State Law Adviser in the State Presidents Office. A few stories in this book relate some of my experiences during this time.

Whilst in private practice as a member of the Cape bar, I was appointed to advise the government during the Kempton Park negotiating process which culminated in the adoption of South Africas first fully democratic constitution in 1993. The majority of the other stories relate to my experiences during this period.

Next page