Dedicated to the memory of Henry and Marie Cruywagen.

Contents

Acknowledgements

T HIS BOOK WAS supported by a Taco Kuiper Grant for Investigative Journalism, for which I am exceedingly grateful. The majority of the research done outside of Cape Town and the Western Cape was made possible by this grant.

To Robert Plummer, Marlene Fryer and Bronwen Leak of Zebra Press, thank you. Your patience, support and editorial insights are gifts that I treasure.

Louise Korentajer and Margaret Titlestad got me interested in this project, and Louise unselfishly showed me what friendship can mean: Thank you. When writing, one needs sustenance, cajoling and encouragement. Without quiet places to think, write and plan, I would have been at a loss, and Izak and Corn de Wet offered their tranquil stone cottage on the lagoon in Wortelgat at a pivotal time. The solitude was essential.

Thanks also to my wife Lianda, Colin and Lebo Cruywagen, Johan Leibrandt and Anton Harber, and Siobhon Tregoning, for generously opening up the Estate in Paarl. Thank you to Jan and Toekie de Necker: you lived through these times and took the political changes in your stride. Thank you, too, to Ayjay and Maggie Jantjies, Lionel and Rose Roode, Clive and Elsabe Vlotman, Linda Jacobs, Andre Cruywagen, Marietjie van Zyl, Daphne Engelbrecht, and my children Yasser, Rameez, Fazlin, Ziyaad and Riyaad.

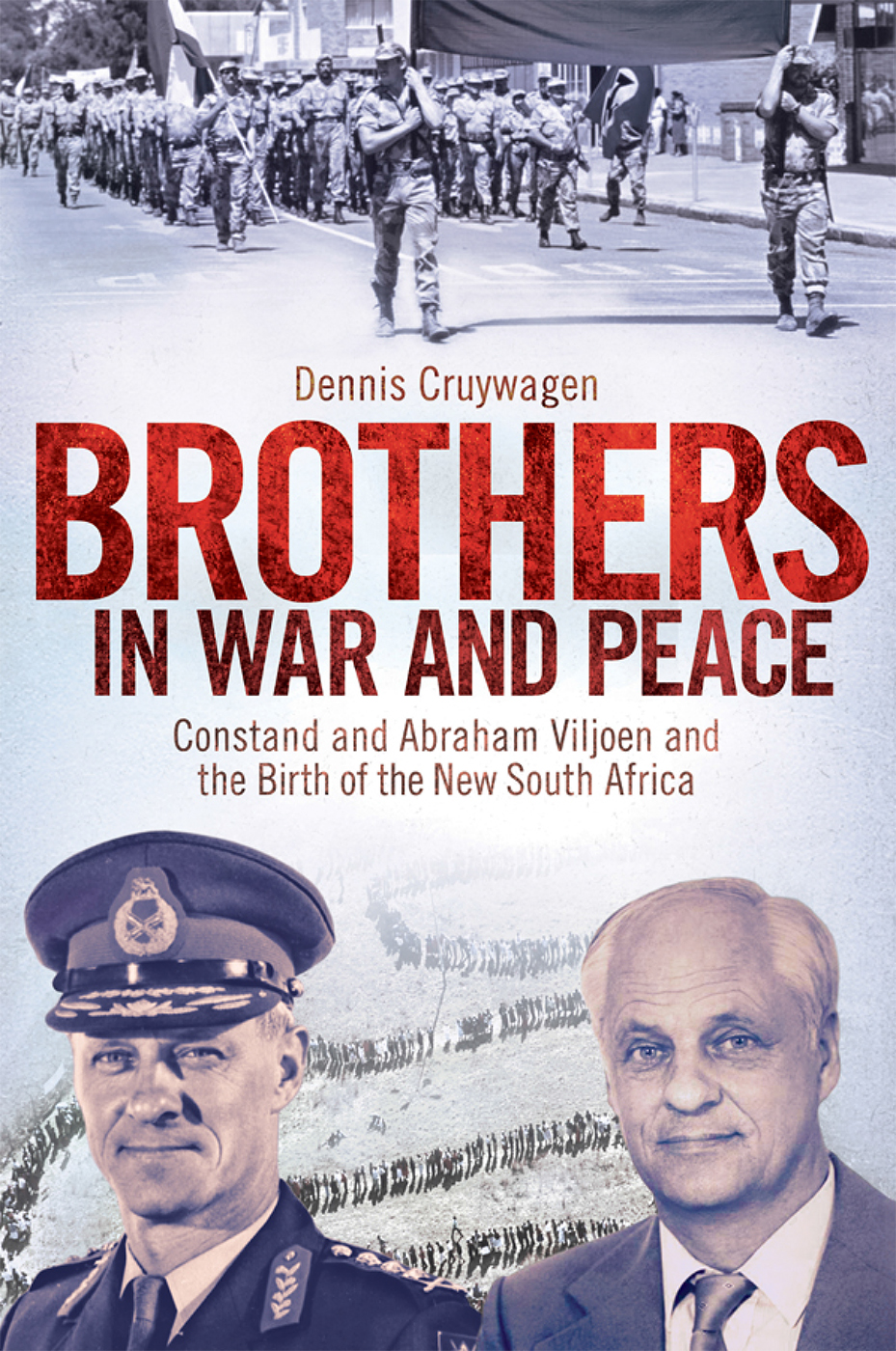

A number of people allowed me to interview them for this book. They include F.W. de Klerk, Jaap Durand, General Tienie Groenewald, Marie Haasbroek, Braam Hanekom, Jrgen Kgl, Augusta Marais, General Georg Meiring, Corn Mulder, General Chris Thirion, Colonel Piet Uys, and the two remarkable and courageous brothers, Abraham and Constand Viljoen. Others asked to remain anonymous but nonetheless spoke to me. Thank you for your time and for your trust. I must add that the books conclusions are nevertheless my own.

DENNIS CRUYWAGEN

JUNE 2014

Abbreviations and acronyms

ANC: African National Congress

AVF: Afrikaner Volksfront

AWB: Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

BOSS: Bureau of State Security

COSAG: Concerned South Africans Group

CP: Conservative Party

DP: Democratic Party

FF: Freedom Front

FNLA: National Front for the Liberation of Angola

HNP: Herstigte Nasionale Party

IDASA: Institute for a Democratic Alternative for South Africa

IEC: Independent Electoral Commission

IFP: Inkatha Freedom Party

MK: Umkhonto we Sizwe

MP: member of Parliament

MPLA: Peoples Movement for the Liberation of Angola

NP: National Party

PAC: Pan Africanist Congress

PFP: Progressive Federal Party

SABC: South African Broadcasting Corporation

SABRA: South African Bureau for Racial Affairs

SACC: South African Council of Churches

SACP: South African Communist Party

SADF: South African Defence Force

SSC: State Security Council

SWAPO: South West Africa Peoples Organization

UN: United Nations

UNISA: University of South Africa

UNITA: National Union for the Total Independence of Angola

UWC: University of the Western Cape

Introduction

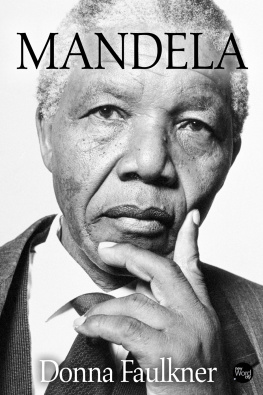

T WENTY-SEVEN YEARS BEHIND bars is more than enough time for a man to learn how to control and discipline his emotions, facial expressions and thoughts, to give nothing away. During his time as a political prisoner, Nelson Mandela learnt how to mask his feelings, to deny his jailers any advantage, no matter how small.

After his release in 1990, Mandelas life became a frenzied helter-skelter that showed no signs of slowing down. By mid-1993 the president of the African National Congress (ANC) was within sight of the end of his journey to bring political freedom to all South Africans. There had been setbacks, events that threatened to derail the process towards a democratic election, such as the assassination of popular ANC leader Chris Hani by white right-wingers earlier in the year. But through good leadership and political will, the country did not turn to civil war. The constitutional negotiations were back on track and millions of black South Africans were finally beginning to believe that democracy was coming to their land. The rest of the world was also upbeat about the prospect of arguably the most famous political prisoner of the last quarter of the twentieth century becoming president of the only remaining white-ruled country on the African continent. The world wanted Madiba, to pay homage to him, to hear him, to be inspired by this man who had forgiven his persecutors. Outwardly Mandela epitomised confidence, but inwardly he harboured deep concerns about the Afrikaner right wing, for he knew very well that not all white South Africans were prepared to give up or share political power with the black majority.

A man with a voracious appetite for news, Mandela was closely following the rise of the Afrikaner right wing. Knowing that right-wingers occupied key positions in the civil service from which they could cause chaos in society, he regarded them as fearsome enemies and was acutely aware that they could scupper negotiations for democracy. They were angry and still believed it was their birthright as white Afrikaners to rule over the countrys black inhabitants. They were prepared to go to war to ensure that political power remained in their hands. Mandela shared his fears and worries with his inner circle, but he understood that only direct talks between the ANC and the right wing could save the country from plunging into a civil war that would have no winner. He thus tried to reach out to the right wing, but his approaches were always rebuffed. For a while it looked like right-wing leaders had closed the door on any talks with him.

But that all changed one night as Mandela was about to depart on an overseas trip from Jan Smuts International Airport in Johannesburg. Abraham Viljoen, a former lecturer at the University of South Africa (UNISA) and an academic regarded as a leftist, had prevailed upon former student Carl Niehaus to arrange a face-to-face meeting with the ANC president. Although running on a tight schedule, Mandela was intrigued by the possibilities inherent in the request.

It would be no ordinary meeting, for Abraham was the identical twin brother of the former head of the South African Defence Force (SADF), General Constand Viljoen.

At this first meeting, hastily arranged at Jan Smuts, Abraham talked about involving those Afrikaners who were not part of the political negotiations, those seen as part of a lunatic fringe. He thought that the threat from this group could be addressed if the ANC met with his brother and other like-minded leaders to the right of the ruling National Party. Abraham offered to broker these discussions, which, if they ever came off, would not form part of the official constitutional negotiations.