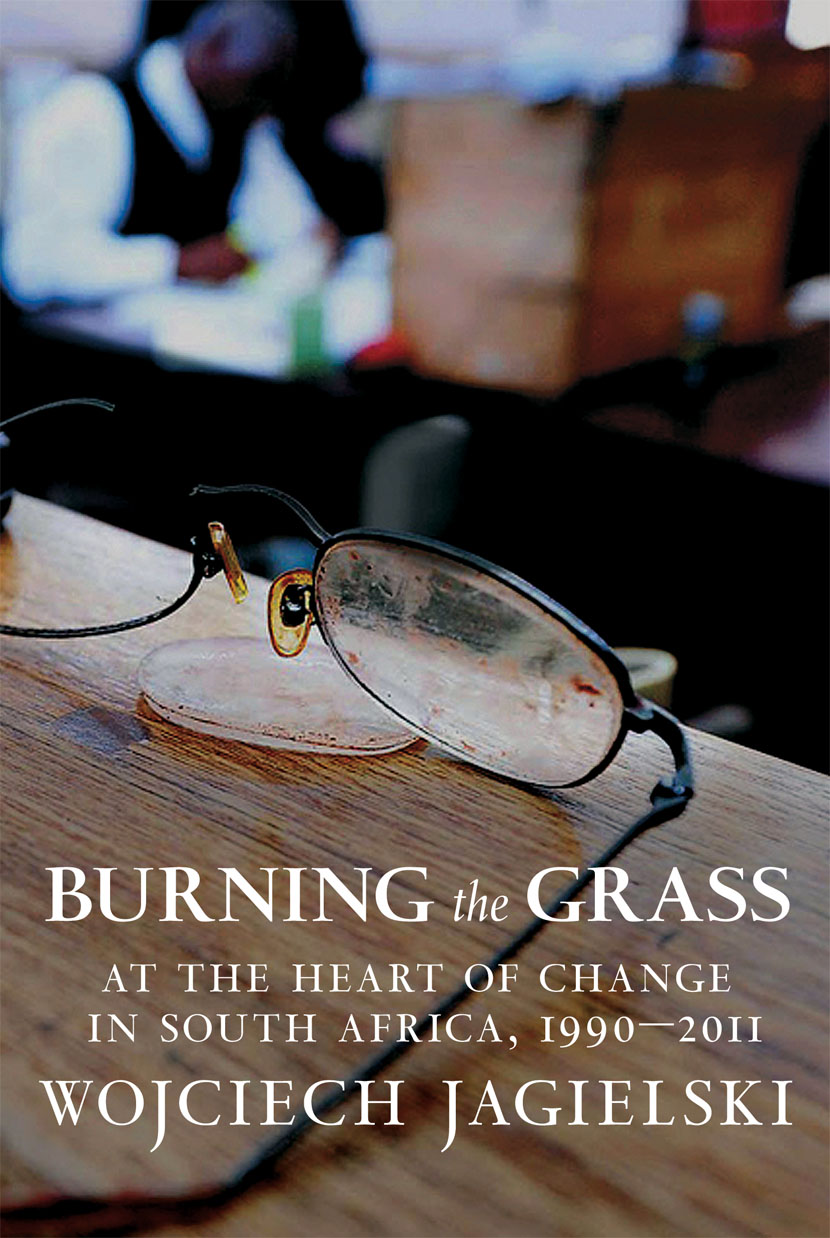

burning the grass

at the heart of change in south africa, 1990 2011

WOJCIECH JAGIELSKI

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

New York Oakland

Copyright 2012 by Wojciech Jagielski

English translation 2015 by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

This publication has been subsidized by Instytut Ksikithe POLAND Translation Program.

Originally published in Polish by Wydawnictwo Znaknunder the title Wypalanie traw, 2012.

First English-language edition.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. To order, visit www.sevenstories.com/textbook or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Book design by Jon Gilbert

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jagielski, Wojciech, 1960- author.

[Wypalanie traw. English]

Burning the grass : at the heart of change in South Africa, 1990-2011 / Wojciech Jagielski ; translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

pages cm

Translated from the Polish.

ISBN 978-1-60980-647-7 (pbk.)

1. Terre Blanche, Eugne N. 2. Politicians--South Africa--Biography. 3. Afrikaners--South Africa--Biography. 4. Racism--South Africa. 5. Apartheid--South Africa. 6. South Africa--Ethnic relations. I. Lloyd-Jones, Antonia, translator. II. Title.

DT1949.T47J3413 2015

968.065--dc23

2015017972

Printed in the United States

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

I used to have a friend in Ventersdorp, a small Afrikaner town on the veld in Transvaal. She was a journalist for the local newspaper.

When I called to tell her I was going to write about the town, and about Eugne TerreBlanche, the man who ran it, she hung up and stopped answering my calls.

Burning the Grass

A pale autumn sun had risen over the town and the surrounding veld.

Easter Saturday was dawning, a time of sorrow and uncertainty. The smoke from burning grass, which had clouded the horizon for the past week, had come closer during the night. Driven by the east wind, it had crept up from the farms across the Skoonspruit River, to the very edge of town. It prompted anxiety, as well as thoughts of punishment, remorse, and paybacks yet to be identified.

First to awake, as ever, was Tshing, the black township adjoining white Ventersdorp. It got up as the first rays of sunlight were starting to dispel the darkness and chill of night. As the rooftops gradually loomed out of the dawn mist, smoke from the hearths rose above them, to the sound of hens clucking, gates creaking and then crashing shut.

The streets slowly began to fill with people. Men in navy-blue overalls carefully locked their front doors and gates behind them, then came out onto the road to join others, heading on foot to the white town over the hill.

Black town councillor Benny Tapologo, still half asleep, could imagine the scene taking place around him on all the nearby streets; it was the invariable morning stirring of the black township, heading for the white districts.

Benny, however, had no plans to get up. On Saturdays the town hall was closed. As he lay in bed, basking in the luxurious thought of a day off work, Benny kept delaying the moment when hed get up, putting off all the pleasures that lay ahead of him that day. He had decided to wash his car that morning, his white Nissan SUV, and that evening he was going to watch a soccer match on television.

Raymond Boardman had got up too early, and reached town too early, long before the bank opened.

He left his car downtown, then, glancing at his watch and calculating how much time he had, he automatically set off along the road, slowly being flooded with cold morning sunlight, that ran toward the black ghetto.

It was so early that he met Tswana women on their way to clean, launder, and iron at the houses in Ventersdorp. He also passed black men in heavy cotton overalls heading for the white town. Some of them were standing at the town limits, near the Caltex gas station, to wait for the farmers who would come here in search of laborers to work on their farms, and would choose the strongest, fittest, and bestthe rare few.

As a boy, Raymond had often come here with his father if there was a lack of hands to do the work on their farm or something had to be done that none of their workers could manage. We need more blacks, his father would then say. Time to make a trip to the Caltex.

Every time he passed the Caltex gas station in his car, Ray mond was reminded of this process of selecting people from among others, all alike, in the same navy-blue or gray overalls and rubber shoes. And the eager way they clambered into the back of the truck. They seemed already on the move before his father had pointed a finger to say you, you, and you. They were in such a state of readiness that they seemed to sense his decision a split second before he did, or perhaps they were trying to force him to make the right choice. Raymond felt relief at the thought that he hadnt had to do that for a long time now. His own blacks were enough for the work on his farm; sometimes there was even a lack of jobs for them to do, and then they were forced to look for work in town.

At the Caltex gas station he stopped and turned back toward the white town. Now he was walking along with the men who hadnt stopped at the gas station. They had jobs in the white houses, and were so intent as they walked ahead that they seemed to be trying to anticipate the white housewives wishes to do with watering and cutting their lawns, weeding their flowerbeds, and fixing their fences, driveways, and roofs.

There still wasnt a living soul downtown, though usually by this time of day there was plenty of traffic about. In the silence and emptiness, Raymond found a shady bench on a square outside the new town hall, by the triumphal arch. There he sat until late morning, bank opening time, gazing at the wall of the courthouse. In the night, or maybe at dawn, someone had painted some black sevens on it, joined to form a swastikathe emblem of the white brotherhood, a symbol of purity and good, of the never-ending war against the Antichrist.

Ten oclock had struck when a red delivery truck stopped outside the Blue Crane Tavern, located on the town line. Henk Malan, owner of the bar, watched through the window as the driver got out of his vehicle and walked across the parking lot, nervously looking around him.

A stranger, thought Henk. He knew why the man had got out of his car. As he unhurriedly dried his hands on a towel, he took a good look at him. I bet hes not a customer, he decided. Whites only ever dropped in at the Blue Crane to ask the wayhow to get to the highway to Coligny without going through the black township. The locals almost never looked in here. They called the Blue Crane a shebeen, a black drinking den, as if it were a disreputable dive, and not a decent bar.

They avoid me like the plague, thought Henk angrily.

The whites didnt want the blacks to have their own bar in Ventersdorp. They were afraid that by opening a bar on the edge of town Henk would lure them out of the ghetto. And in this town the blacks were meant to stay in their place.