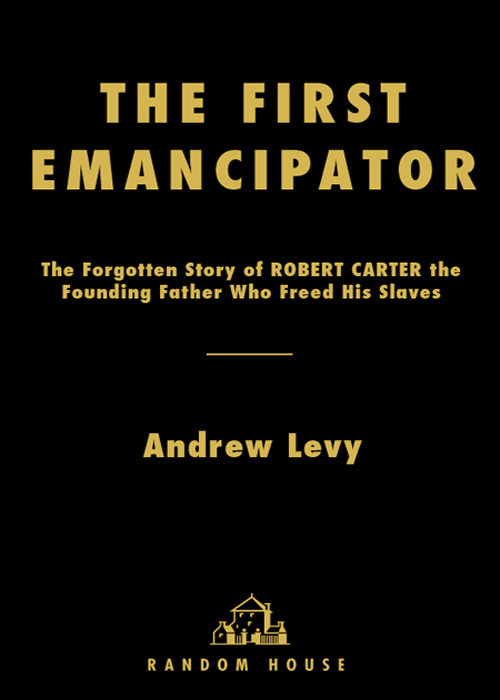

Andrew Levy - The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves

Here you can read online Andrew Levy - The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Random House Publishing Group, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

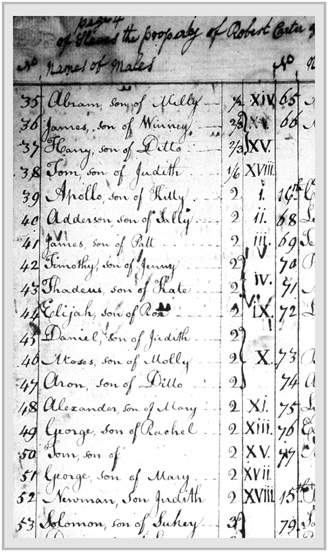

How did Carter succeed in the very action that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson claimed they fervently desired but were powerless to effect? And why has his name all but vanished from the annals of American history? In this haunting, brilliantly original work, Andrew Levy traces the confluence of circumstance, conviction, war, and passion that led to Carters extraordinary act.

At the dawn of the Revolutionary War, Carter was one of the wealthiest men in America, the owner of tens of thousands of acres of land, factories, ironworksand hundreds of slaves. But incrementally, almost unconsciously, Carter grew to feel that what he possessed was not truly his. In an era of empty Anglican piety, Carter experienced a feverish religious visionthat impelled him to help build a church where blacks and whites were equals.

In an age of publicly sanctioned sadism against blacks, he defied convention and extended new protections and privileges to his slaves. As the war ended and his fortunes declined, Carter dedicated himself even more fiercely to liberty, clashing repeatedly with his neighbors, his friends, government officials, and, most poignantly, his own family.

But Carter was not the only humane master, nor the sole partisan of freedom, in that freedom-loving age. Why did this troubled, spiritually torn man dare to do what far more visionary slave owners only dreamed of? In answering this question, Andrew Levy teases out the very texture of Carters life and soulthe unspoken passions that divided him from others of his class, and the religious conversion that enabled him to see his black slaves in a new light.

Drawing on years of painstaking research, written with grace and fire, The First Emancipator is a portrait of an unsung hero who has finally won his place in American history. It is an astonishing, challenging, and ultimately inspiring book.

Andrew Levy: author's other books

Who wrote The First Emancipator: The Forgotten Story of Robert Carter, the Founding Father Who Freed His Slaves? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

![Jenny Carter - Fuzzy Logic(2021)[Carter et al][9783030664749]](/uploads/posts/book/265335/thumbs/jenny-carter-fuzzy-logic-2021-carter-et.jpg)

RANDOM HOUSE | NEW YORK

RANDOM HOUSE | NEW YORK