Pagebreaks of the print version

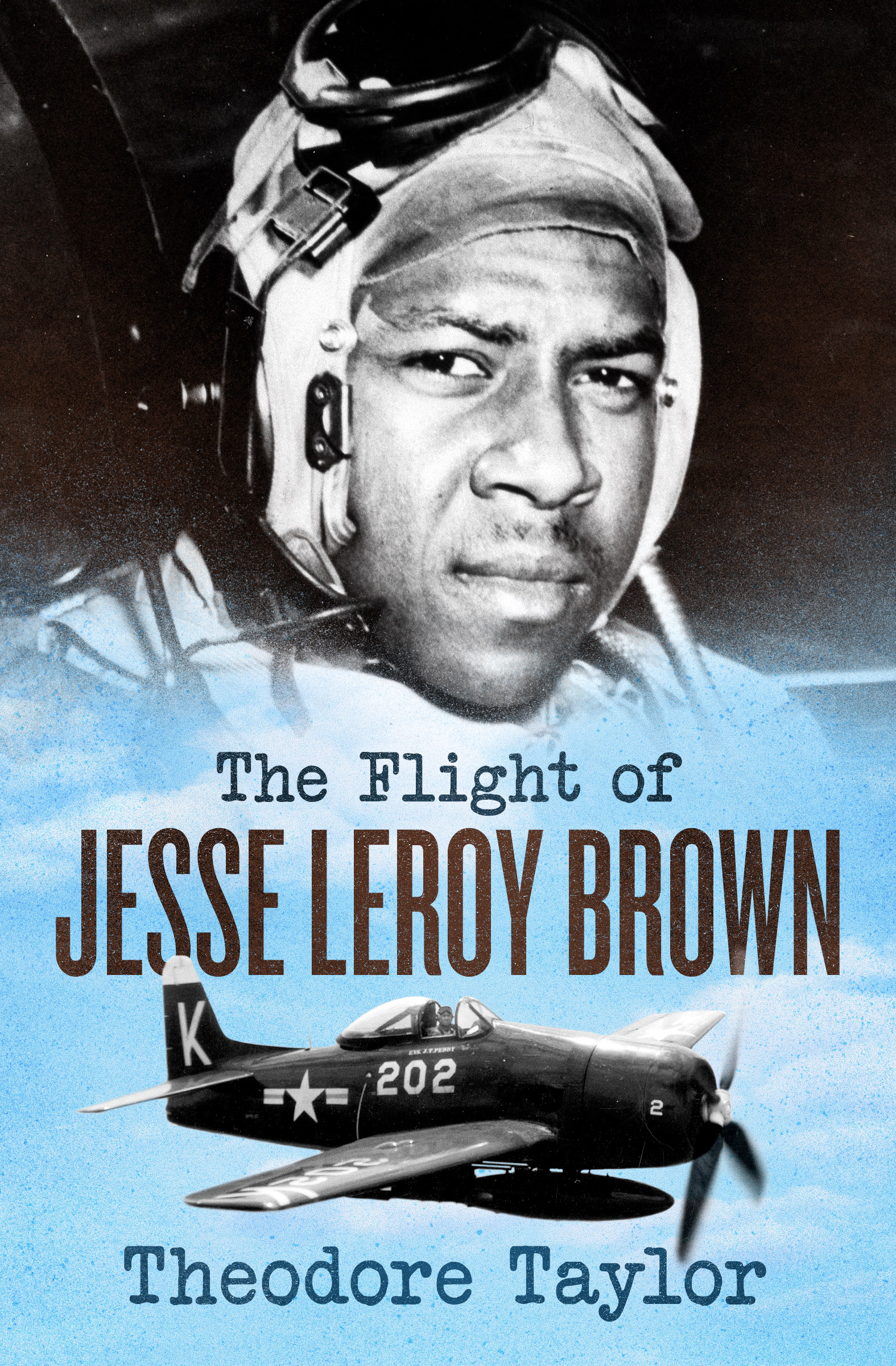

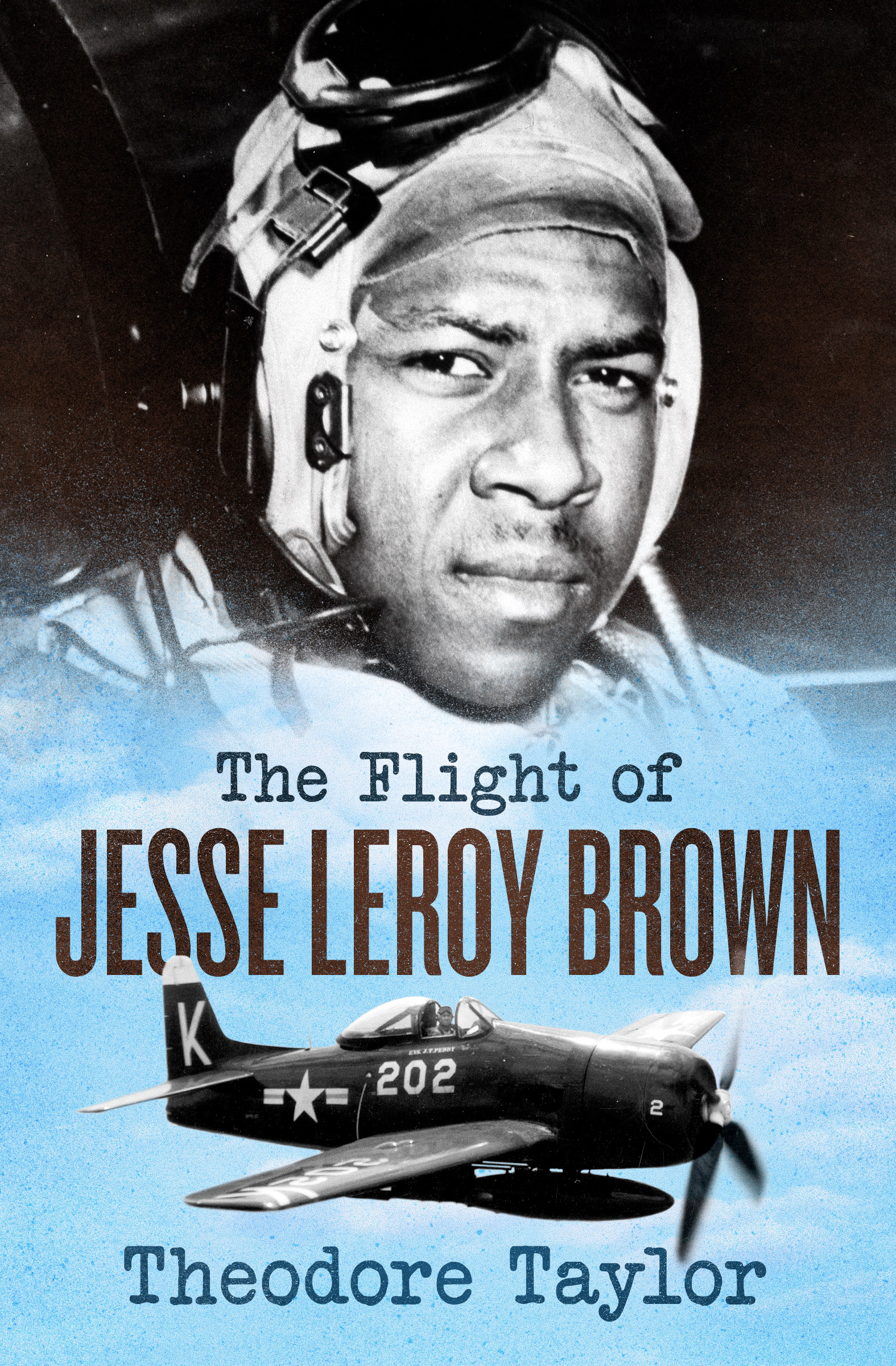

The Flight of Jesse Leroy Brown

THEODORE TAYLOR

For

Daisy Pearl Brown Thorne; Pamela Brown Knight;

William, Lura and Fletcher Brown;

Jessica Leroyce Knight; Jamal Knight

It is my hope that Jesse will serve as a shining role model for all young Americans, especially young African Americans, both male and female.

T HEODORE T AYLOR

Laguna Beach, California

January 1998

Preface

Though little is known about him, Eugene Bullard is believed to have been Americas first black pilot. Rare photos display a stern, almost angry face and piercing eyes. Unable to serve his own country because of segregation and the color of his skin, Bullard flew combat missions for France during World War I and was awarded the Croix de Guerre, that nations highest military medal.

Denied entry into the few flying schools of the early 1920s, Bessie Coleman, born in 1893 in Texas of black and American Indian parents, also went to France to learn how to fly. She said, The air is the only place free of prejudice. In 1922 she was licensed by the Fdration Aronautique Intrnationale, becoming the worlds first black aviatrix. As a barnstormer, putting on aerial shows with other black pilots across the country, she was killed in Florida at the age of thirty-three on April 30, 1926, diving her plane from 3,500 feet, failing to pull out.

The first black pilots license, No. 7638, was issued in 1928 to C. Alfred Anderson. Other notable black aviation pioneers of that era were Hubert Julian, William Powell, Thomas Allen, and James Banning. These fliers were followed in the Chicago area and Los Angeles by Harold Hurd, Cornelius Coffey, Willa Brown, and Janet Waterford.

Beginning in the late twenties and extending well into the thirties, black communities turned out to watch air circuses with black pilots and parachute jumpers and wing walkers, flying off farm fields on Saturdays and Sundays, offering rides for as little as two dollars.

They were doing exactly what white pilots were doing, flying the fabric-covered open-cockpit biplanes, held together with wire and spit, loving every minute of it, often sleeping on hay in black farmers barns at night.

The famed Tuskegee Airmen of World War owed their existence to such pilots as Eugene Bullard, Bessie Coleman, and C. Alfred Anderson. They chipped away at the closed doors of military aviation by proving they could fly.

As a naval reservist LTJG (lieutenant junior-grade), Id been recalled to active duty following North Koreas invasion of South Korea in June 1950, having served in both the Merchant Marine and the Navy during World War II. I was assigned to the cruiser Newport News until someone in the Bureau of Naval Personnel discovered I was a newspaperman.

Soon I found myself sitting at the Navy Press Desk, Department of Defense Office of Information, servicing the Pentagon press corps. Having written for four daily newspapers, it was more my present line of work than gunnery.

I think I first read about Jesse Brown while a reporter for The Orlando Sentinel-Star. It was an Associated Press story and picture, out of Jacksonville, saying that hed broken the color barrier to become the Navys first Negro pilot. He was smiling broadly as the gold wings were pinned on his chest. I also recall a picture of him in Life magazine.

I remember the AP story saying he was from Mississippi, a sharecroppers son. Knowing the Navy, with its tendency at the time to assign all black personnel to galleys as cooks and food servers, or to clean officers staterooms, I wondered how he had done it; how painful his struggle must have been, one Negro swimming alone upstream in a river of white pilot-hopefuls and their often biased instructors.

Many people have been involved in the telling of Jesses storyhis widow, his brothers, his longtime friends; the pilots who trained with him and flew with him; his own many letters, his own conversations with his family, wife, friends, and fellow pilots. In the preparation of this book, I had complete access to his training and flight records; to the logs of Squadron 32 and the USS Leyte, from which he operated.

Above all, this is a human story, not one of whirling propellers, and the use of dialogue has been constructed from tapes, letters, and interviews with the participants. Use of the word nigger, shocking to todays ears, was prevalent in the South and elsewhere during his life. African American was seldom if ever used. I have attempted to be true to the times and locales.

On duty the morning of December 5, 1950, when the first communiqu concerning Ensign Jesse Brown came from the Far East Naval Command, I quickly gathered as many details as I could and wrote the press release about what had happened at Somong-ni, certain there was a larger story to be told. For years after I began writing books, whenever I read anything about the Korean War, I thought of Jesse Brown.

PART I

Somong-ni, North Korea

December 4, 1950

On this particular Monday the weather off the northeast coast of Korea remained very much like that encountered in the North Atlantic during deepest winter: gales and intermittent snow. The afternoon sky was dark gray and the sea was gray, furrowed with curling white wave-tops. Stiff breezes crossing the deck hit faces like an icy towel.

Task Force 77, the carriers Leyte and Philippine Sea, the great battleship Missouri and the sixteen other vessels of the Seventh Fleet were relentlessly plunging along into the wind, guiding on the cruiser Juneau. Only in the very worst weather were the aircraft grounded.

For three desperate days now, priority orders had been to provide increased maximum air support day and night to the 15,000 encircled Marines fighting their way along the bloody body-strewn 15-foot-wide ice-encrusted mud road to Hungnam, the captured North Korean port. Evacuation awaited.

Ensign Jesse Leroy Brown had flown the day before in one of the Leytes sixty-nine sorties. In addition to bombs, rockets, and machine gun fire, thirty-six napalm pods had been dropped on two parallel ridges a mile long, frying Chinese communist troops who had recently entered the war against South Korea. More than 100,000 CCP troops surrounded the Marines.

Browns best friend on the Leyte, LTJG Lee Nelson, had flown earlier that morning across the frozen Chosin Reservoir, located not far below the Manchurian border, making attack runs against the troops that were feeding into the pincer movements along the northwest shore. Hed skimmed the windblown ice, and after his debriefing, had talked about it with Jesse at early lunch.

Its ugly out there, Nelson said, meaning the weather.

Any ack-ack [antiaircraft fire]?

The usual around Chosin. Small arms.

You get any?

I dont think so. Nelsons plane hadnt been inspected as yet for bullet holes.

Doug Neill, Squadron 32s skipper, had been giving his pilots hell for going in too low. He didnt need shootdowns or maintenance problems.

Jesse said, Man, am I sleepy. I was up late writing to Daisy and Pam.

Nelson laughed. Youll wake up once you get on deck. Its cold, Jesse. Same as yesterday. The pilots wore longies, cover-alls, maybe a sweater, rubber antiexposure suits, and fleece-lined boots and gloves.