F or a while, it seemed as if nothing much would ever be written about the Vietnam War. Most Americans did not want to be reminded about the first major military defeat in U.S. history. As far back as fall 1968 there were signs that public opinion had shifted against the war. The Tet Offensive launched at the end of January 1968 by North Vietnam and the Viet Cong stunned the American public. Even though the U.S. military had defeated the tremendous effort by the North Vietnamese to turn Tet into an American Dien Bien Phu, and despite the fact that Viet Cong losses during the offensive had eliminated them as an effective fighting force, Americans were left with the impression that we would never be able to thwart the North Vietnamese governments efforts to make all of Vietnam a communist state. Sickened by the unending parade of the horrors and images of American dead on the nightly news, and subjected to an intense antiwar barrage of news coverage that attempted to treat every action of the U.S. military in a negative light, most public opinion expressed disgust and disillusionment. Americans wanted an end to the war and withdrawal from Vietnam.

Early in 1968, while flying combat missions on my second combat cruise, the local Kiwanis Club in my small hometown in Oklahoma invited me to address its members upon my return to the States. Not many local boys were involved in Vietnam, and the local press had reported some of my actions, so the patriotic folks back home wanted to hear a firsthand account of my combat experiences. By the time I returned on leave in October 1968, the invitation had been forgotten. No one wanted to hear more about our ignoble debacle in Vietnam. They just wanted us out of there.

U.S. forces finally withdrew in 1973. Congress voted to cut off funds for the South Vietnamese, and in 1975 we were treated to the spectacle of the last retreat from Saigon, with Huey helicopters evacuating our embassy from the roof. The anti-U.S. and antiwar forces in the media and elsewhere in society had achieved complete victory. Although anticommunist voices in the United States had warned of the consequences of early withdrawal, few in this country were prepared for the extent of the revenge exacted on South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos after our capitulation. Images of fleeing Boat People and the squalor of overcrowded refugee camps began to fill our television screens.

The uneasy burden of responsibility for this debacle began to fall on the activist antiwar movement, and prominent voices in the movement began trying to deflect responsibility for the human tragedy befalling Southeast Asia. Wild fantasies such as the films Apocalypse Now and The Killing Fields attempted to focus the blame on the United States for its policies and on the U.S. military for teaching the peace-loving people of Southeast Asia to brutalize one another. It was not until the early 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan restored pride in our nation and in our military, that Vietnam veterans began to tell their stories to America. Books describing their experiences began to appear on bookstore shelves, and the history of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia began to be reevaluated. The old anti-U.S. and antimilitary voices also began to stir. The film Platoon, directed by Oliver Stone, exemplifies their attempts once again to discredit U.S. involvement in Vietnam. This film, which received the Academy Award for Best Picture and was hailed as the definitive portrayal of the American military in Vietnam, highlights drug use by the soldiers, atrocities against civilians, maniac officers, and fraggingthe practice of soldiers trying to murder their superior officers. These things did happen, but they were not the norm. To portray them as such does a terrible disservice to the thousands of American servicemen and service-women who performed their duties and fought for their country with honor.

New generations born after our involvement in Vietnam are reaching maturity and learning about that time in our history. Unfortunately, there has been very little reality and a lot of fantasy written for them to use to formulate their impressions of our nations struggle against communism and of our military services during the sometimes not so Cold War. It is for this and other reasons that I wrote this book.

The experiences I describe here really happened, and what I say is as close to truth as my memory and memorabilia can make it. To fill gaps in my memory I have sometimes had to create details, but these are based on actual occurrences. For the most part, though, this account relates my experiences just as they happened. I use the actual names of real people, places, battles, and events, though the book is not intended to be a scholarly history. I was personally involved in most of what I describe here, although some events happened to others and were simply told to me.

However it is accepted, what I have written is the way it really was. Remember it, History, because in the course of human events things like these are bound to happen again.

To my huge embarrassment and everlasting gratitude, my wife, Alma, saved all the letters I wrote home, which amount to an almost daily diary of my time on cruise. The letters have been an invaluable source for dates and a great help in sharpening details blurred by time. Aviation writer and military historian Peter Mersky proved to be an amazing resource of photographs and valuable contacts whose assistance were vital in the production of this work. I am thankful to Alma and to my sons, Chad and Scott, for providing the encouragement to pursue publication in spite of obstacles, and to Chads wife, Natalie, for proofreading the original manuscript. Many thanks go to my production editor and my copyeditor, Marla Traweek and Mindy Conner, for holding my hand during the process, and to Rick Russell for seeing value in my work.

T he great gray side of the USS Bon Homme Richard (CVA-31) loomed above us like a prehistoric cliff dwelling as we stood in an unhappy little knot on the pier. It was late January 1967, and the weather in San Diego was living up to Southern Californias reputation for having a near-perfect climate. The temperature was in the high sixties, under clear skies with gentle breezes. Red, white, and blue national bunting hung from the roofs of the dockside warehouses. The Naval Air Station North Island band played continuous marches and pop tunes in a futile attempt to lighten the mood of this singularly morose occasion. Departure day for the 1967 WESTPAC cruise for the Bon Homme Richardnicknamed the Bonnie Dickand Air Wing 21, which would be embarked in the Bonnie Dick for the duration of the cruise, had finally arrived. The colored clothing worn by the crowd of dependents, relatives, and well-wishers there to see us off swirled in marked contrast to the drab, haze-gray Navy paint on the ship and dockyard equipment. Dungaree-clad sailors of the line-handling parties stood by the thick, chest-high bollards that had the huge hawser ropes of the carriers mooring lines draped around them. The sharp tang of fresh salt air mixed with whiffs of diesel oil, steam, and cooking smellsthe body odor of any large ship. Across San Diego Bay I could see the light tan buildings of the Naval Training Center catching the first rays of the morning sun as it cleared the highlands east of San Diego. NTC, or Boot Camp, was where I had started my life in the Navy four and a half years ago. It seemed as if all the hard things I had to do in my life occurred in San Diego.

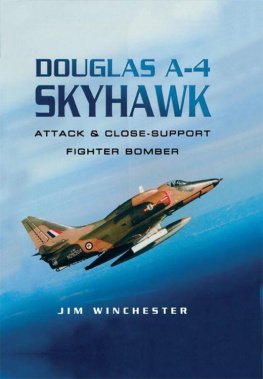

Alma, my bride of six months, and my mother and father stood trying to make small talk to postpone the inevitable moment of my parting. The day after reporting to Attack Squadron 212 (or VA-212, the designation VA meaning fixed-wing attack in Navy parlance), I was assigned to fly an A-4 Skyhawk to San Diego to be loaded on board the ship. Mom and Dad had driven from Oklahoma to see their only son off to war, and Alma and my folks had driven from our apartment in Hanford to meet me. Perhaps only a handful of people in that crowd fully understood, as my father did, the significance of this day. My father had departed these same shores for battle in the Pacific at Iwo Jima and Okinawa twenty-three years before. Some of the people in that crowd were unknowingly bidding a final farewell to their loved ones. Some departing that day would not return, and some would return only after years in a POW camp. Alma was biting her lower lip to keep it from trembling and fighting back tears; Mother was already weepy; and Dad was trying to be Dad, ever-strong for me. I couldnt get a grip on my feelings. I felt the pain of imminent separation from my wife, the excitement of embarking on a great adventure, and apprehension about the unknown trials ahead. But I did not yet feel fearI was still too ignorant of things to come.