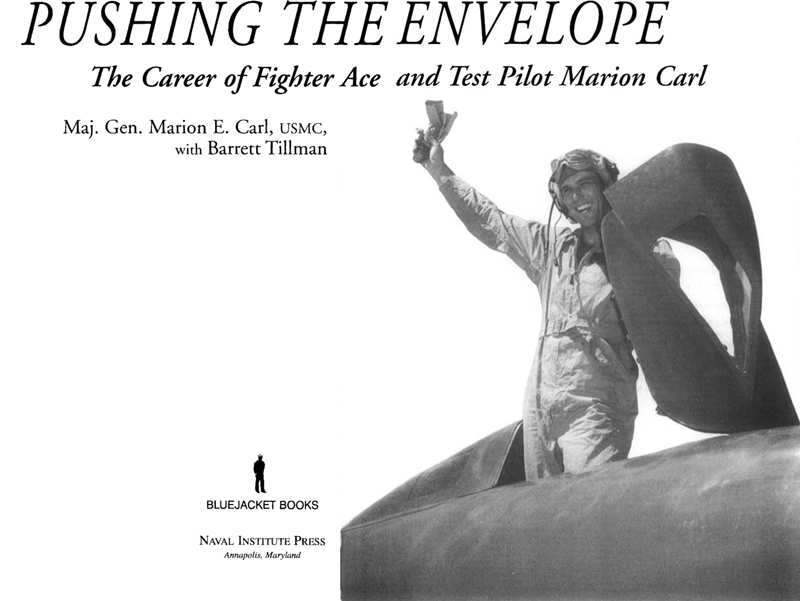

Pushing the Envelope

The latest edition of this work has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

1994 by Marion E. Carl and Barrett Tillman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

First Bluejacket Books edition, 2005

ISBN 978-1-61251-548-9 (eBook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Carl, Marion E., 1915-1998

Pushing the envelope: the career of fighter ace and test pilot Mario Carl / Marion E. Carl, with Barrett Tillman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Carl, Marion E,. 1915-1988. 2. Fighter PilotsUnited StatesBiography. Test pilotsUnited StatesBiography. I. Tillman, Barrett. II. Title.

UG626.2.C374A3 1994

358.434092dc22

93-36021

CIP

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

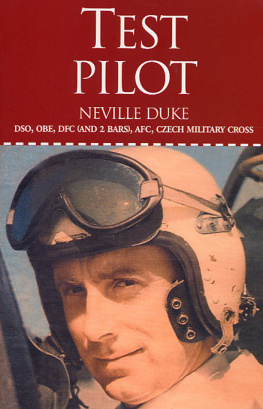

Title page photo: Marion Carl set the world speed record on 25 August 1947 in this Douglas Skystreak (D-558-I) at Edwards Air Force Base. (Douglas Aircraft Co.)

For Edna, of course

Contents

Remembering Marion

T he two-lane blacktop of Route 99 East winds through the lush greenness of the Willamette Valley between Portland and Salem. Farm vehicles and pickups are always around the Oregon hamlets, so it is not a fast way to get to where youre going.

But I wasnt in a hurry. I was thinking of Marion Carl, who had been killed defending his wife during a robbery ten days before. At age eighty-two, he had died fighting on 28 June 1998.

At the north end of Woodburn, a signpost caught my eye: Carl Road Northeast. Two miles north is a cheery greeting: Welcome to Hubbard, Home of the Hop Festival. Population 2,185.

In 1939, when Marion Eugene Carl was commissioned a second lieutenant and aviator in the U.S. Marine Corps, Hubbard was home to 387 souls. There had been even fewer when he was born there in a tent on 1 November 1915. But that humble beginningsurely the humblest of any great aviatorlaunched Marion on a spectacular career. He was a fighter ace, test pilot, holder of three world records, and survivor of World War II clandestine flights over China and then Vietnam, where he finished his combat career as a brigadier general current in jets and helicopters.

In aviation, we speak of the natural pilotsthose apparently born with a gift for flying. They are exceedingly rare, as normal humans are not genetically engineered for performing in three dimensions. Marion Carl apparently was: he soloed after two and a half hours of dual instruction (eight to ten is usual) and just got better. Ive always said that Ive only known two geniusesgenius being defined as an innate ability to consistently perform extremely difficult tasks extremely well. Marion was one of them. The other was Douglas Aircraft designer Ed Heinemann, whose products figured prominently in Marions career. Ed had almost no engineering education, but he produced an exceptional variety of supremely successful military and experimental aircraft.

Marion had the flying gene. It must have been similar to the divine spark that gave Mozart his awesome ability from childhood and endowed Ted Williams (another Marine aviator) with unmatched skill at batting.

If that sounds like hyperbole, so be it; I challenge anyone to prove otherwise.

If Marion was anything, he was a hunter. One of his partners said, Marion will hunt anything on two legs or four; one engine or two. He was competitive as a fighter pilot and as a deer hunter. But, as his neighbor Capt. Joe Reese elegized, Marion wasnt rash or excitable. I think that where others saw daring or even brashness, Marion saw acceptable risk. He had enormous self-confidence because he possessed enormous skill and knowledge. That combination allowed him to succeed at high-risk ventures that others wouldnt try. Perhaps the best example occurred over Guadalcanal in September 1942. Marion was attacked in the traffic pattern by an audacious Zero pilot who was deterred by alert antiaircraft gunners. Cranking up his wheels, Marion gave his Wildcat full throttle and gave chase.

Over the beach, in view of hundreds of U.S. Marines, the Japanese aviator accepted battle. He abruptly reversed course, approaching the apparently vulnerable Grumman from overhead. Marion pulled his nose into the vertical, got a brief sight picture, and pressed the trigger. His aim was superb; the Zero exploded, showering parts onto the beach.

The Japanese pilot probably was Lt. Junichi Sasai, an ace and leader. He could not have known that his opponent was the finest fighter pilot in the American campone possessed of the willingness and ability to risk an all-or-nothing act. For, when Marion pulled his nose above the horizon, he was fully committed to win or lose. Had he missed that vertical deflection shot, he would have been caught beneath the Zeros guns, out of speed and out of options. Instead, he remarked, This is the kind of place I likewhere you have to shoot em down just so you can land.

Unlike every other Guadalcanal veteran I ever knew, Marion harbored no resentmentlet alone hatredof the Japanese. His was a supremely professional attitude, and he enjoyed meeting former enemies. The appalling atrocities customary to the Japanese military are too well known to ignore, but Marions war wasliterallyabove all that. Once, he said, I prefer to refer to victories rather than kills. Though he killed quickly and efficiently, he did not know the meaning of malice.

One measure of Marions status among his contemporaries was the assumption that he held the Medal of Honor. Though Marion was never a ribbon hunterhe didnt even apply for the dozen or more Air Medals and Distinguished Flying Crosses he could have gained in Vietnamhe learned in 1943 that he had been nominated for the Congressional. His explanation was that his commanding officer (CO), Maj. John L. Smith, already wore the pale-blue ribbon and, presumably, their squadron would not be awarded a second Congressional Medal of Honor. However, I learned later that the Navy Department would not forward the recommendation because the Army objected to the number of leathernecks being awarded major gongs during that phase of the war. The fact was, of course, that the Marines were engaged in the most intense combat from the summer of 42 into early 43. But World War II was fought on many fronts, including Washington, D.C.

Next page