BFI Film Classics

The BFI Film Classics series introduces, interprets and celebrates landmarks of world cinema. Each volume offers an argument for the films classic status, together with discussion of its production and reception history, its place within a genre or national cinema, an account of its technical and aesthetic importance, and in many cases, the authors personal response to the film.

For a full list of titles in the series, please visit

https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/series/bfi-film-classics/

THE BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

BLOOMSBURY is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2021 by Bloomsbury on behalf of the

British Film Institute

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

www.bfi.org.uk

The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK and the distributor of Lottery funds for film. Our mission is to ensure that film is central to our cultural life, in particular by supporting and nurturing the next generation of filmmakers and audiences. We serve a public role which covers the cultural, creative and economic aspects of film in the UK.

Copyright Alex Dudok de Wit 2021

Alex Dudok de Wit has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as author of this work.

For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. 6 constitute an extension of this copyright page.

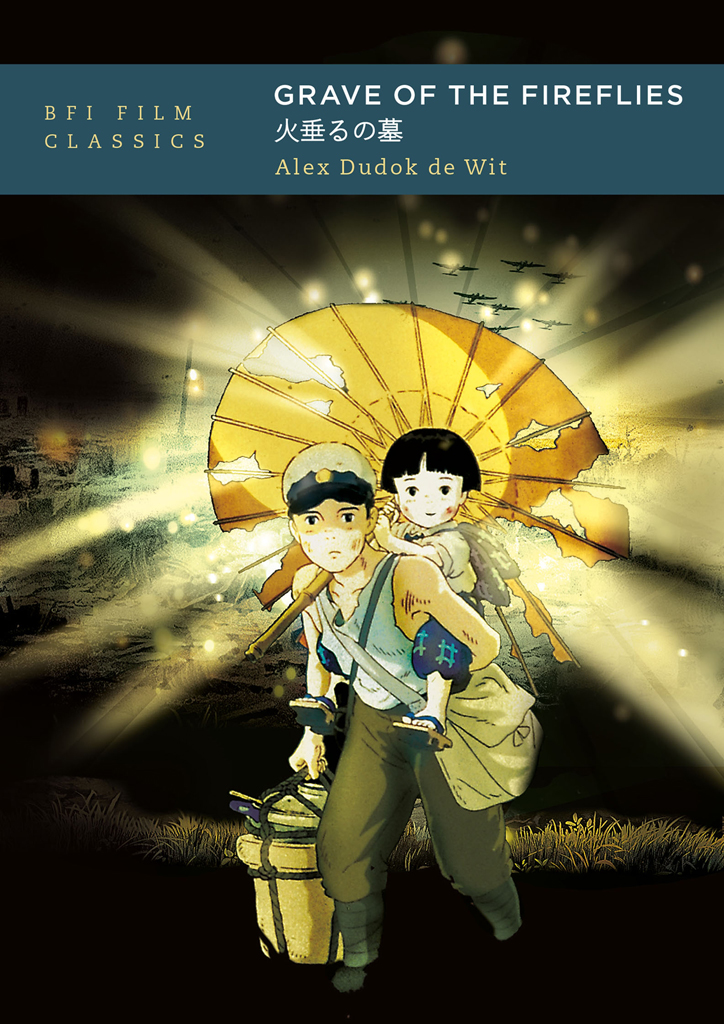

Cover image: Akiyuki Nosaka/Shinchosha. All Rights Reserved

Series cover design: Louise Dugdale

Series text design: Ketchup/SE14

Images from Grave of the Fireflies (Isao Takahata, 1988), Shinchosha; Momotaro, Sacred Sailors (Mitsuyo Seo, 1945), Shochiku Co. Ltd.; Pica-don (Renz Kinoshita, 1978), Studio Lotus; Barefoot Gen (Mori Masaki, 1983), Madhouse/Gen Productions; My Neighbour Totoro (Hayao Miyazaki, 1988), Tokuma Group/Studio Ghibli; Tokyo Story (Yasujir Ozu, 1953), Shochiku Co. Ltd.; Forbidden Games (Ren Clment, 1952), Silver Films (Paris)/Mondex Films; Ghiblis Scenes: Visiting the Japan Depicted by Isao Takahata (Toshikazu Sat, 2014), BS Nippon Corporation/TV MAN UNION, INC.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: PB: 978-1-8387-1924-1

ePDF: 978-1-8387-1923-4

ePUB: 978-1-8387-1925-8

Produced for Bloomsbury Publishing Plc by Sophie Contento

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com

and sign up for our newsletters.

Contents

I am indebted to Rebecca Barden and her colleagues at Bloomsbury for expertly guiding an untried author.

Many people sharpened my words and ideas by discussing the film with me or giving feedback on my manuscript. I am especially grateful to Ilan Nguyn, Yasu Kawata, Cat Philps, Jonathan Clements, L. Halliday Piel and two anonymous readers of my first draft.

Carys Gaskin at StudioCanal was tirelessly helpful with sourcing images, and Sophie Contento turned my plain Word documents into a beautiful book. I thank them both.

Merci, maman et papa.

Thank you, Bryony.

Authors note

Japanese names in this book are presented in the Western order, surname last. Quotations of the films dialogue are taken from the English subtitles on StudioCanals 2013 Blu-ray release, which are accurate enough for the purposes of my analysis. All other translations are mine, except where otherwise stated.

In March 1945, as the Pacific War entered its endgame, the United States launched a concerted campaign to destroy Japans cities with fire. The stated aim was to cripple the countrys industrial base; in practice, civilians were indiscriminately attacked. Urban Japan, dense with wood and paper, proved highly vulnerable to incendiary bombs. By the wars end on 15 August, almost all cities of appreciable size lay in ruins.

On 5 June, incendiaries fell on the eastern part of Kobe, the countrys main overseas port. In the ensuing chaos, fourteen-year-old Akiyuki Nosaka fled his burning home alone. Later that day, at a makeshift hospital, he found his sixteen-month-old sister and mother, who was severely burned; his father was never seen again. While their mother recovered, Nosaka and his sister drifted between refuges: first a relatives home near Kobe, then a bomb shelter, and finally an acquaintances house in a different province. Malnutrition stalked them throughout, eventually taking the little girls life on 21 August. Nosaka survived to become one of postwar Japans most original writers, but the traumas of these months lived on with him, resurfacing time and again in his work. He revisited this period in his best-known story, the novella Grave of the Fireflies (Hotaru no haka, 1967).

Once the US Air Force had disabled Japans major metropolises, it set its sights on smaller cities. On 29 June, the campaign reached Okayama, 70 miles west of Kobe. Awoken by the bombs, nine-year-old Isao Takahata found his home empty but for his older sister.say he had saved her life. They were reunited with their family after two days. Although relatively fortunate, Takahata would rank this experience as the worst of his life. Four decades later, by then a prominent director in Japans animation industry, he decided to turn Nosakas novella into a feature. He recalled those two days so vividly that details from them ended up in his film.

Takahatas Grave of the Fireflies (1988), then, is an unusually personal adaptation of a remarkably intimate text. The memories and philosophies of its two authors are entwined, sometimes inextricably, in its simple story. Nosaka was understandably protective of his novella, which he long suspected might be unfilmable. It took Takahata, a man who shared some of his formative experiences, to convince him otherwise. Here was a director with an exceptionally precise artistic vision, working in an environment Studio Ghibli geared towards realising that vision, with a medium animation that resolved the problems of adaptation.

His film, for which he also wrote the screenplay, is broadly faithful to the novella. Yet just as Nosaka lightly fictionalised his experiences in his writing, Takahata made further adjustments. The significance of these various changes will be examined in the chapters ahead; for now, a synopsis of the film already reveals a few divergences from Nosakas life. Fourteen-year-old Seita and his four-year-old sister Setsuko lose their mother and home in the Kobe raid; with their father at sea, they move in with a distant relative, whose hostility prompts them to live instead in an unused bomb shelter; for want of food, their health deteriorates; Setsuko dies shortly after the wars end, Seita a month later.