Contents

CULTOGRAPHIES

CULTOGRAPHIES is a list of individual studies devoted to the analysis of cult film. The series provides a comprehensive introduction to those films which have attained the coveted status of a cult classic, focusing on their particular appeal, the ways in which they have been conceived, constructed and received, and their place in the broader popular cultural landscape.

OTHER TITLES IN THE CULTOGRAPHIES SERIES:

THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW

Jeffrey Weinstock

DONNIE DARKO

Geoff King

THIS IS SPINAL TAP

Ethan de Seife

SUPERSTAR: THE KAREN CARPENTER STORY

Glyn Davis

BRING ME THE HEAD OF ALFREDO GARCIA

Ian Cooper

THE EVIL DEAD

Kate Egan

BLADE RUNNER

Matt Hills

THE HOLY MOUNTAIN

Alessandra Santos

DANGER: DIABOLIK

Leon Hunt

BAD TASTE

Jim Barratt

QUADROPHENIA

Stephen Glynn

FASTER, PUSSYCAT! KILL! KILL!

Dean DeFino

FRANKENSTEIN

Robert Horton

THEY LIVE

D. Harlan Wilson

MS. 45

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas

DEEP RED

Alexia Kannas

STRANGER THAN PARADISE

Jamie Sexton

SERENITY

Frederick Blichert

THE SHINING

K. J. Donnelly

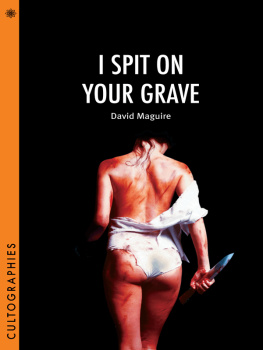

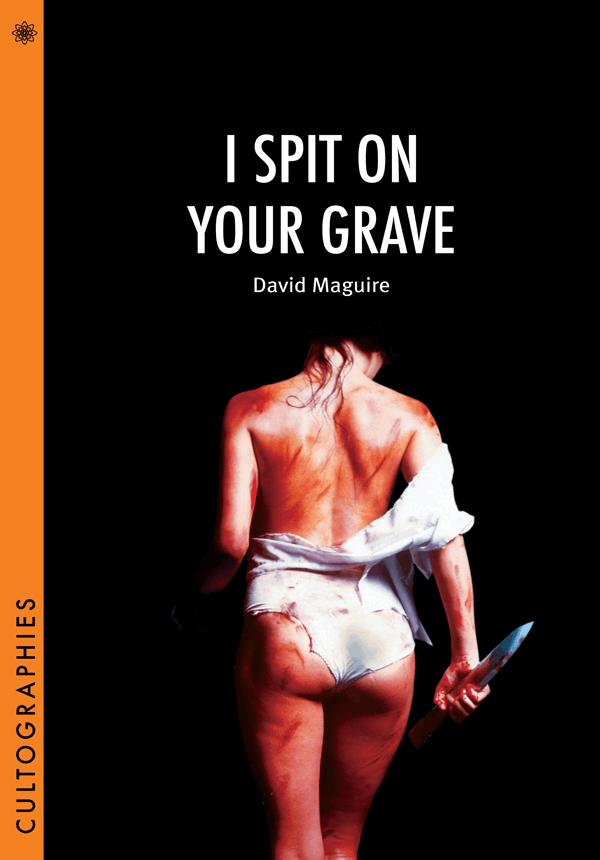

I SPIT ON YOUR GRAVE

David Maguire

A Wallflower Press Book

Published by

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2018 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-85128-2

Wallflower Press is a registered trademark of Columbia University Press

A complete CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-231-18875-3 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-231-85128-2 (e-book)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Series and Cover design by Elsa Mathern

CONTENTS

There will be no spitting on graves for the following:

Jonathan Marshall, for first proposing that I write a book on this topic thank you!

Karen Scott, for her advice and encouragement in overseeing my dissertation for I Spit on Your Grave which then mushroomed into an obsession with the rape-revenge genre generally.

Stratford Kirby, for his never-ending support and enthusiasm throughout every step of this books creation. When youre writing about a much maligned film on a topic that (quite understandably) upsets a lot of people, your options of discussing it with anyone are limited!

Amanda Adrienne, for restoring my faith in the rape-revenge genre with her film Savaged and her kind support throughout the writing of this book.

And finally, Jamie Bernadette, star of I Spit on Your Grave: Dj Vu; who, despite being incredibly busy, was always very gracious when I pestered her with interview questions.

From its unflinching subject matter (the brutal gang-rape of a beautiful career woman and her subsequent revenge), its battles with censors and mauling by critics, the picketing of its screenings by feminists and the politicians who deemed it a corrupting influence on society, it is a film that continues to divide opinion and enflame passions. It is, depending on your point of view, either the most powerful or repulsive rape revenge melodrama ever filmed (Crowdus and Bloom 2003: 32). While many condemn its misogyny, others praise it for raising uncomfortable issues about sexual violence, then unheard of in exploitation or even mainstream movies. It is deeply distressing to watch it was in 1978 and remains so today. And yet that is not to say that it is a bad film without merit, only that the films reception was, and continues to be, complicated. To fully understand ISOYGs growth from celluloid pariah to cult film, one has to explore its unique position in, and impact on, the cultural, historical, political and gender landscape of its initial release. While other exploitation films of the 1970s/1980s and the UK video nasties scandal have been consigned (often quite rightly) to the trashcan of time, ISOYG has found itself mythologised and revered by the countless rape-revenge films that have followed. Despite being condemned for its sick attitude towards women (Ebert 1981: 55), director Meir Zarchis film has spawned official and unofficial franchises, and even a spoof. Cynics may argue that these productions are simply cashing in on the cultural memory of the original, and there is undoubtedly an element of this, but there is also evidence to suggest that ISOYG is being updated to explore more complex issues such as vengeance and retaliation in a post-9/11world relating to the war on terror. In so doing, the films official remake and sequels challenge contemporary viewers in different ways to the original, questioning ideological and ethical issues relating to torture, revenge and violence.

In light of its impact on film culture and the increasing number of pro-feminist reappraisals of the film something which is in itself problematic in light of the clear exploitation route the movie went down and the (male) audience such productions are designed to appeal to it is perhaps fitting that, forty years on, Zarchis film is re-examined as an important part of cinema. While other challenging independent horrors of the era such as Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972) and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) have all since been re-evaluated and acclaimed (with the latter added to the permanent collection of New York Citys Museum of Modern Art), ISOYG is still brushed under the carpet as a complete turn-off (Newman 2011: 76). But just as these once-vilified films are now regarded as having something important to say about society, ISOYG is no exception: the most disturbing thing about the film will not be the profanity or its nudity or its violence; it will be the awareness perhaps for the first time in their [viewers] lives of how unnervingly traumatic rape is. These feelings will occur because I Spit on Your Grave takes rape, and the feelings of rape victims, far too seriously (Starr 1984: 54; emphasis in original). It can be argued that Zarchis insistence on tackling rape in the manner that he does is a key reason why many continue to find the film so repulsive.

While ISOYGs remakes, the sequels, and even the trailers all participate in a pleasurable game of repetition which has contributed to turning the film into a fetish (Zanger 2006: 16), its imitators of which there are many remind us of just how creative, daring and provocative the original was.