Table of Contents

To Punjab and its people, to set right the record of the volcanic events, in the hope that Indias diverse communities withstand divisive forces and prosper in unity and peace

Contents

E VEN IN THE BEST OF TIMES, PERCEPTIONS OF AN EVENT OR A situation vary. Catastrophic events in particular tend to obscure objectivity, divide people and often cause facts to fall by the wayside. Operation Blue Star and its aftermath were cataclysmic events of this nature, making India go to war with itself. The nation lost a Prime Minister, a chief minister, a former army chief, thousands of innocent citizens and some not-so-innocent ones. However, nearly four decades later, we still hear varying versions of what happened, why and how it happened. Facts are sacred, but whose facts are they? It is one persons truth against anothers, your interpretation versus theirs.

In June 1984, the Indian Army marched to AmritsarOperation Blue Star was under way. Some saw it as an invasion of the sacred space of the Golden Temple, while some others viewed it as a military operation to clear the area of gun-wielding terrorists.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated a few months later. Carnage followed on the streets of Delhi and elsewhere, with over 3,000 innocent Sikhs being murdered. Some believe it was genocide, while others considered it a spontaneous reaction to the murder of their beloved leader. For some, Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was a shaheed, a martyr, as publicly pronounced by the jathedar of the Akal Takht in 2003. Others, however, viewed him as a zealot responsible for over two decades of Punjabs turmoil, misery and mayhem.

I was an eyewitness, and at times an actor, howsoever insignificant, as this moment of history unfolded. What I saw or didor what I failed to doneeds to be told. My conscience, more than anything else, impels me to tell my facts and my interpretation of the events that transpired over the troubled decade and a half surrounding Operation Blue Star. To leave things unsaid would be to blank out history. Therefore, I feel the need for an objective and factual account of the events and happenings. This is my attempt in the pages of this book.

In Punjab, terrorism has been eliminated decisively. However, the deep, fundamental ethno-socio-religious fault lines that led to the turmoil in the state still persist. History has an uncanny habit of repeating itself, and we have to be on guard, for only the civilizations that draw lessons from their history and move forward prosper.

Being on the rolls of the government, this is the earliest opportunity I received to publish the present work, post my superannuation as chief secretary, Punjab, and thereafter as chief information commissioner, Punjab, under the Right to Information regime. And I do not regret this interregnum because the passage of years has helped crystallize issues and cooled down tempers. In these thirty-eight years, a lot has been said and written about Operation Blue Star and the chaos in Punjab. An abundance of pop history books and documentaries and a few eyewitness accountsmostly hearsayhave been published. Everything, however, has not been said and probably may not be said for a while, considering the sensitivity of the subject and the security imperatives.

I have, however, narrated as much as I know and chronicled it honestly. I hope, as passions mellow over time, people within and outside the establishment will be more receptive of this work. My words may displease some; however, the intention is not to hurt any feelings or apportion blamethough in historical accounts that may be unavoidablebut to initiate dialogue, open the way to introspection and, most importantly, move towards reconciliation and closure over a tragic past.

K HALSA JI, KAMMAR KUS LO, SAMAY AA GAYA HAI [KHALSA JI, THE time has come, gird your loins], proclaimed Sant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale in his clarion call imploring the Sikh community to rise against the Government of India. It was 8 or 9 June 1984, soon after the end of Operation Blue Star. Bhindranwale was on a Pakistani TV channel, sitting upright and wearing the traditional Sikh choghah with a kammar kasa or cummerbund tightly tied around the waist. I heard him live on Lahore TV, along with millions residing along the international border. Technology had enabled Pakistan to carry transmissions deep into India, compromising our territorial sovereignty. The telecast was repeated many times over, with a tacit message that Bhindranwale would make an important announcement in the days to come.

A few days later, my maternal uncle, a retired police officer, was the first from my extended family to reach Amritsar. He was inquisitive, almost interrogatory, as he said, Take me to the tunnel via which Sant Ji escaped. My denial that there was no tunnel or that the Sant was dead found no acceptance.

He countered, But P.C. Sethi, the Union home minister, said in Parliament that extremists were taking refuge in a tunnel in the complex. The ministers statement was refuted by the then president of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), Atma Singh, as late as 28 April 1984, but the rebuttal notwithstanding, the minister had set up the gullible devotees fantasythe tunnel, some said, extended up to the Wagah border. When I persisted with my refutation, he demanded, Where is Gurdev Singh? Let me speak to him. You are new to the place and do not know.

Gurdev Singh Brar was my predecessor as deputy commissioner, Amritsar. Of the many rumours, a popular one then was that Gurdev Singh had escorted Bhindranwale to safety through a secret tunnel. For the devout, the rumours were truth. Gurdev Singh had not been seen in public since the day he imposed curfew in Amritsar on 3 June 1984. The government had not yet formally announced Bhindranwales death, and even after it did so, the Damdami Taksal, the Sikh seminary to which Bhindranwale belonged, continued to deny it. People believed the latter, for they had seen him in flesh and blood on TV exhorting the Khalsa to revolt. And seeing is believing. This served as excellent propaganda for the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to sustain and instigate the frayed Sikh tempers.

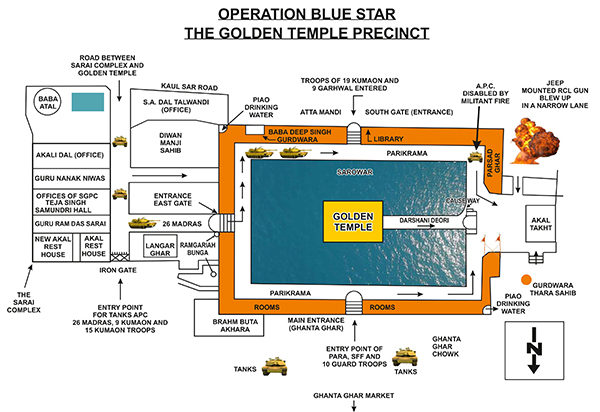

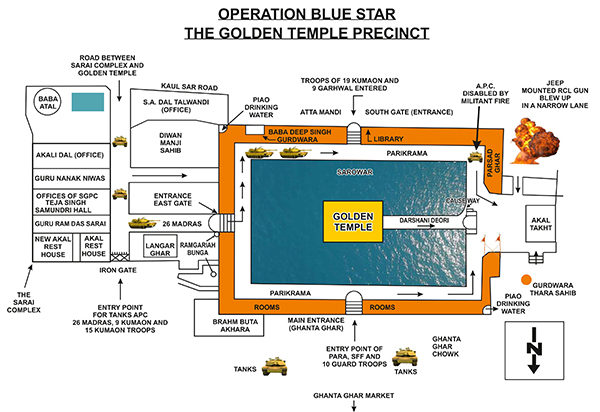

By the middle of May 1984, Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) troops had been deployed around the Golden Temple. The militants had set up a chain of armed fortifications encircling all strategic points in and around the temple complex. The observation posts on high vantage points gave early warning of any movement around the temple precincts. The brick-lined pigeonhole openings in the walls, sandbagged doors, windows, ventilators and pillboxes with clear lines of sight and fire had converted the temple into a hunting ground. These battlements provided a sense of security and protection to the militants, who operated in a well-controlled and coordinated manner. Obviously, an effective command-and-control structure was in position.

On 27 May, CRPF troops at Akhara Bala Nand exchanged fire with militants, a situation that was repeated on 30 May. On 1 June 1984, the CRPF closed in, firing from the rooftop observation posts built on high-rise private properties overlooking the temple, mainly houses and hotels. There was an intermittent exchange of fire starting from noon till about 8 p.m. Eleven civilians, including two women, died and more than twenty-four were injured. Bullets hit the temple complex, by one count, thirty-two in all. Curfew was imposed in Amritsar for thirty-two hours, starting 9 p.m. on 1 June. Allegedly, the firing started as unprovoked sniping by the CRPF with the objective of drawing counter fire from the militants. That would give away details of their emplacements and weaponry.