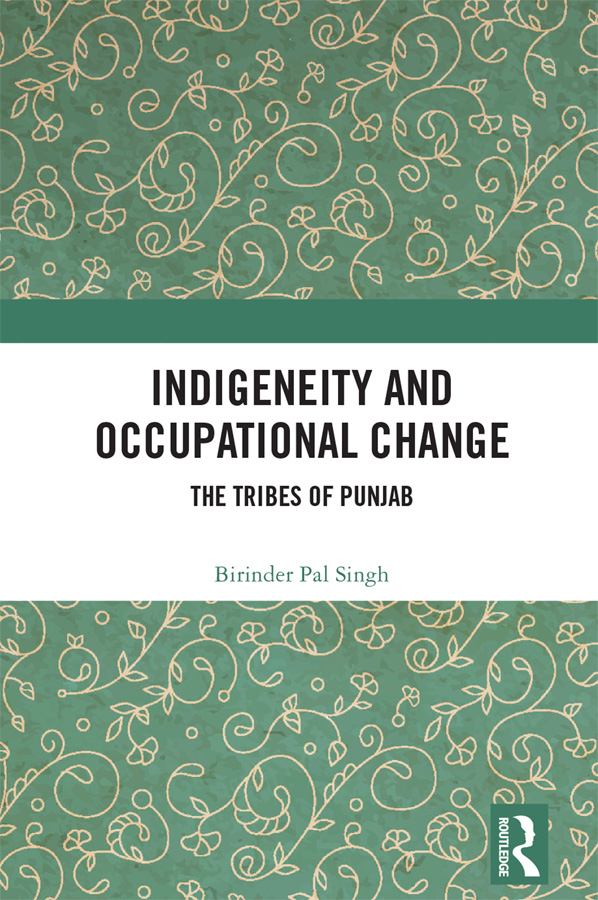

Indigeneity and Occupational Change

This book is about the presence of the absent the tribes of Punjab, India, many of them still nomadic, constituting the poorest of the poor in the state. Drawing on exhaustive fieldwork and ethnographic accounts of more than 750 respondents, it explores the occupational change across generations to prove their presence in the state before the Criminal Tribes Act was implemented in 1871. The archival reports reveal the atrocities unleashed by the colonial government on these people. The volume shows how the post-colonial government too has proved no different; it has done little to bring them into the mainstream society by not exploiting their traditional expertise or equipping them with modern skills.

This book will be of great interest to scholars of sociology, social anthropology, social history, public policy, development studies, tribal communities and South Asian studies.

Birinder Pal Singh is Professor of Eminence in the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Punjabi University, Patiala, India, where he joined as lecturer in 1976. He was a Fellow of the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla (19931995). His areas of study include tribal and peasant communities and the sociology of violence. His publications include: Economy and Society in the Himalayas: Social Formation in Pangi Valley (1996); Problems of Violence: Themes in Literature (1999); Violence as Political Discourse: Sikh Militancy Confronts the Indian State (2002); Punjab Peasantry in Turmoil (ed.; 2010); Criminal Tribes of Punjab: A Social-Anthropological Inquiry (ed.; 2010) and Sikhs in the Deccan and North-East India (2018). He has about 70 research papers and articles and has worked on seven research projects.

Indigeneity and Occupational Change

The Tribes of Punjab

Birinder Pal Singh

First published 2020

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2020 Birinder Pal Singh

The right of Birinder Pal Singh to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-0-367-33586-1(hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-429-32133-7(ebk)

Typeset in Sabon

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

Contents

The idea to undertake the present study has its roots in the project An ethnographic study of the nomadic, semi-nomadic and denotified tribes of Punjab (2008a) given by the Punjab government to the department of Sociology and Social Anthropology at Punjabi University, Patiala, to ascertain the tribal character of some communities contesting for tribal status. Until then, for us too, these tribal communities were absent from the state. Once having worked with them on their ethnography, some interesting aspects of their lives and history came to light that generated more interest in inquiring into their present and the past. The inquisitiveness to look into their history becomes more pronounced when one finds them declared as criminal tribes more than a century and a half ago. How come these people living with bare minimum means of subsistence and roaming around with or without some cattle could disturb the law and order of the land? Why were they perceived as a potential threat to the mighty colonial power? Why did such people thriving in forests for centuries become conspicuous to the foreign regime that declared an aggressive operation to hunt them out from their habitat and subject them to civilisational processes of production and lifestyle? If they were criminals, what sort of crime they were committing and why? These are a few major questions that generated interest to look into the patterns of their livelihood and the occupations they were engaged in to make a living.

Three state universities established well over four decades, each with a department of sociology and the fourth one and the oldest in the region at Panjab University, Chandigarh (union territory), never made these people the subject of their research and study. Two of these universities with their centres for the study of exclusion and inclusive development too focused on the Scheduled Castes and within them on Balmiks (Harijan/Mazhabi) and Ramdasias/Ravidassis (Chamars) and did not bother about the tribal communities as tribes. The Institute for Development and Communication, Chandigarh, however, does include four tribes in its study Status of Depressed Scheduled Castes in Punjab (1996) but that too not as tribal communities but one amongst other depressed castes. This is despite the fact that Sher Singh Sher, a sociologist, had produced empirical studies on the Sikligars and the Sansis of the region as early as 1966 and 1965 respectively.

In the absence of social scientific studies of the tribal communities in Punjab, two types of studies are available. One is by the insiders, the members of own community writing largely about the socio-cultural aspects of own people. Darya (1997) writes about the Sansis, Inder Singh Valjot (2009) and Mohan Tyagi (2013) about the Bazigars. The first and the third are university teachers and the second one a practising lawyer. These works are in Punjabi. Other works in the same genre are by Kirpal Kazak on Sikligars (1990) and Gaadi Lohars (2005), and by Bhupinder Kaur on Gujjars (2010a). Chahals (2007) work on Baurias is also in the same mould but in Hindi.

The present study of occupational change over generations in the tribes has been charted out with an intention to confirm their presence in the state where their very existence is negated. They are no longer acknowledged as tribal people but as a variant of the numerous low castes living on the periphery of the villages or in the slums of the state towns. The detailed interviews with respect to their traditional occupations and especially those of their elders parents and grandparents show beyond doubt that the majority of them were nomadic, so much so, that the respondents have returned invariably nomadism as their ancestors traditional occupation.

This is not at all clear that why such communities, duly identified and numerated in the census of 1881 by Denzil Ibbetson and given ethnographic details subsequently by Rose (1883/1970), have been declared to be absent altogether from the north Indian states of Punjab and Haryana. This is a subject of independent inquiry. A few preliminary attempts in this respect did not yield anything. How do the criminal tribes declared denotified suddenly become the Scheduled Castes? It would be interesting to look into the dynamics of certain agency or agencies of decision-making and nondecision-making la Bachrach and Baratz (1970) in the then power structure of the state. How have these communities been propelled out of their due listing in the Scheduled Tribes and included in the larger category of the Scheduled Castes whose share in the Punjab population is largest in the country? It is 31.94 per cent in 2011.