Imperial Frontier

Tribe and State in Waziristan

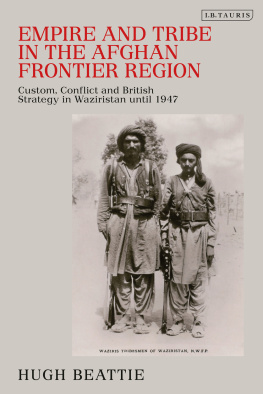

Village Tower near Wana (reproduced by permission of the British Library catalogue number (735/1(5)).

Imperial Frontier

Tribe and State in Waziristan

Hugh Beattie

First published in 2002 by Curzon Press

This edition published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2002 Hugh Beattie

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 0700713093

I would like to express my gratitude in particular to Dr. Malcolm Yapp, emeritus Professor of the History of Western Asia at the School of Oriental and African Studies, who supervised the thesis on which the book is based. For many years I benefited from his ideas and patient encouragement. I would like to thank Professor Akbar Ahmed, currently Visiting Professor at Princeton University, for his help and advice; I am indebted to him for writing a foreword. I would also like to thank Dr. Iftikhar Malik of Bath University College for his considerable contribution to , and Professor Richard Tapper and Professor R.B. Smith of the School of Oriental and African Studies for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. I am grateful to Peter Newbolt for permission to quote from the poem Clifton Chapel by Sir Henry Newbolt. I am also most grateful to Catherine Lawrence for her work on the maps, Dr. Richard Christensen for helping me to find my way around the India Office records at Orbit House, and the staff of the India Office Library and Records, and of the SOAS, Institute of Historical Research and Cambridge University libraries for their assistance over the years. I am indebted to my wife Claire for reading and commenting on successive drafts, and also for her tolerance and understanding while the book has been in preparation.

Akbar S. Ahmed

Hugh Beatties book throw light on Waziristan, a little-studied area of the world. It works on two levels: it is a straightforward and authoritative account of a remote and turbulent area of imperial Britain in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: on another level it underlines the continuing relevance of the tribal groups living in Waziristan to our own times. The book is therefore to be read on both levels and the reader will be able to profit from the idea of the continuing relevance of history to the understanding of what is happening in the Muslim world today.

Beattie sets out to understand tribal organisation, the way religion shaped the encounter between the Muslim tribesmen and the British imperialists, and the relationship between tribe and state. Although the study is historical, it nonetheless contributes to the examination of what anthropologists call segmentary tribal systems. Such tribes are aware of descent from a common ancestor: they subdivide into clans and sub-clans with each living in a specified area, they are egalitarian (conscious as they are of being descendants of a common ancestor) and they are, at least in this case, patrilineal. Segmentary tribal systems discourage the growth of centralised states and the growth of rigid hierarchies in society. The Waziristan material confirms the classic segmentary system.

On the surface the reader may wonder what connection there is between events that took place well over a century ago and our own period. Beatties study provides the answer. Muslim groups responded to British imperialism in two ways: in the cities and in their colleges they often absorbed British values, learned the English language and attempted to join the services; in the tribal areas they often formed groups to resist imperial advances through armed resistance. This pattern can be detected through the Muslim world. So on the one hand in the late nineteenth century great colleges were created in Aligarh, Cairo and Delhi, and on the other there were the great resistance movements of the Sanusi, the Mahdi, and the Akhund of Swat and others along the northwest frontier.

But the expressions of resistance in Waziristan were more than just a response to British imperialism. They were expressions of identity, in fact an act of identity. The tribes of Waziristan have always considered themselves a people apart even in the tribal areas of the North-West Frontier Province. Indeed their adherence to customs, culture and language sets them apart even today.

When I was Political Agent in the South Waziristan Agency in the late 1970s, I never failed to be amused by the expressions of shock and horror on the faces of the visitors from the northern areas representing the finest and best-known Pashtun tribes such as the Yusufzai. They saw the people of Waziristan as almost beyond the pale: crude, brutal, even boorish. Are they also Pashtuns?, they would ask uncomfortably.

In the eyes of the tribes of Waziristan even the Yusufzai, the true blue aristocrats of the Pashtuns, were hardly Pashtuns. They are too soft, they would mutter. Pashtuns need to be tough to fight the world and assert their identity. These people shave, they wear washed and pressed clothes and they dont even carry guns. They were right in one sense. A Wazir or Mahsud in his traditional clothes is a striking figure: the end of his turban thrown over the lower half of his face only showing his eyes darkened with kohl; a murderous looking knife in his belt, and a cross-belt of .303 bullets across his chest; a gun slung across his back. Waziristan is one of the few areas of Pakistan where men still walk about in this manner.

So a story that begins nearly 200 years ago continues into the twenty-first century. It is a remarkable story and it is well told. There are the clashes and skirmishes with British imperialists. There is on that level the ebb and flow of history that defines the attempts at finding an equilibrium between tribe and state. Then comes the independence of Pakistan in 1947 and Pakistans own attempts to absorb the tribes, which are largely successful. Even so the tribes of Waziristan are able to maintain their identity. But it is the last decades of the twentieth century that the effects of what we call globalisation impact on Waziristan and dramatic changes take place. One of these is the emergence of Mullahs or religious leaders who can challenge not only the state itself but also the tribal chiefs within Waziristan. The emergence of this kind of leader also echoes what is happening across the border in Afghanistan itself.

The Taliban in Afghanistan remain a mystery to many people. Young, inexperienced Pashtun men seem to have conquered Afghanistan and are imposing their uncompromising view of life on society. Women and non-Pashtun minorities in particular seem to be suffering. The Taliban are primarily Pashtun tribal groups who wish to impose their Pashtun understanding on society. In that sense Pashtun sociology is coming face to face with the age of globalisation. It is an unhappy confrontation.