First published in Great Britain in 2010 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Editorial matter copyright Jules Stewart 2010

9781844685295

The right of Ruby Mukhia to be identified as Literary Executor and of

Jules Stewart as Editor of this Work has been asserted by them in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline

Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

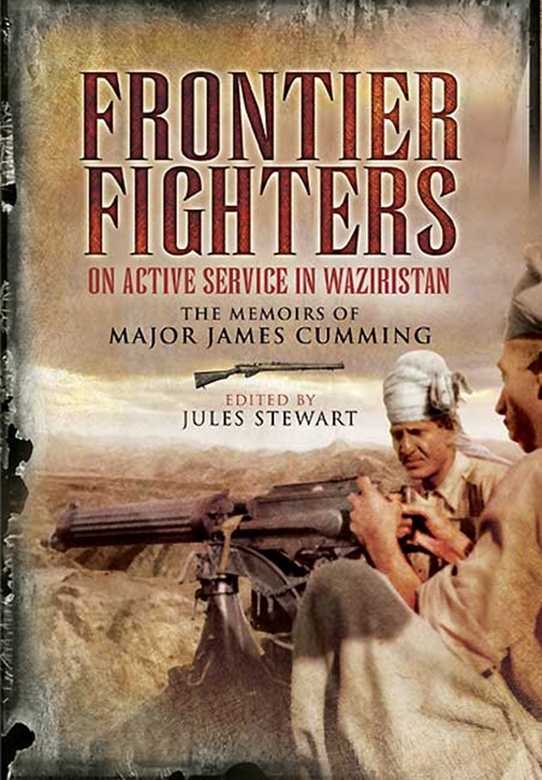

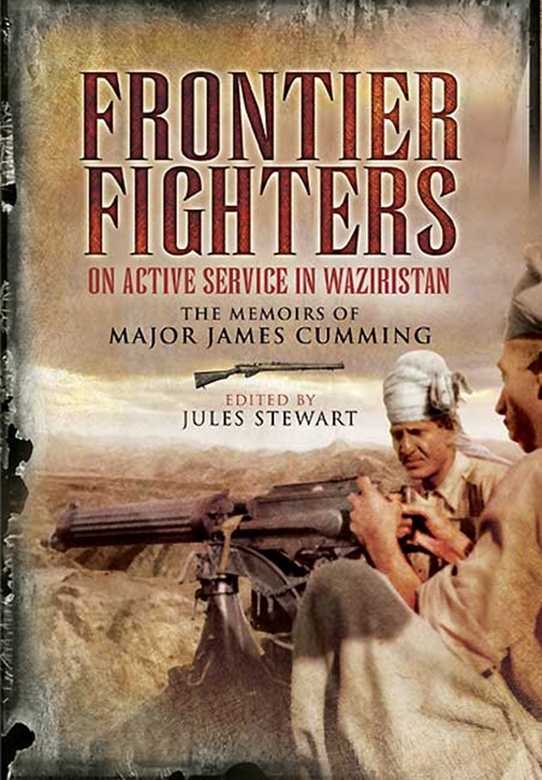

Foreword

Major Cummings memoirs took me back to my soldiering days on the North-West Frontier. During my Army days in Pakistan, I served in the Chitral Scouts, Tochi Scouts, Zhob Militia and also as ADC to the Governor of the North-West Frontier Province. This provided me with a comprehensive view of life on the Frontier and I got to know in depth the various Pathan tribes who inhabit this mostly inhospitable territory. Reading through this young British officers experiences brought to mind rather strikingly how little things had changed several decades later, when I had to deal with the rebellious yet fascinating Pathan tribesmen. I say fascinating because in spite of their warlike and intractable nature, and the trouble they caused us, British officers respected the tribesmens toughness and proud character, as well as their bravery in battle.

It seems quite uncanny how little things have changed in Pakistans tribal territory. If the tribesmen were a handful for the British in Cummings days, as well as for the Pakistan government after Partition when I served on the Frontier, Pakistans tribal belt today represents an even greater threat to stability, and not just on a local level. In the days of the British Raj, soldiers like Cumming had to contend with parties of tribesmen staging raids in the Settled Districts or on military outposts. The punitive expeditions and pitched battles that would follow are described in dramatic detail in Cummings memoirs. Years later, we also had to deal with ambushes when we were out on gasht, or patrol, and Pathan raiders were still crossing the administrative border to steal whatever weapons or goods they could lay their hands on.

Today the tribal belt known as Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) poses a threat on a much greater scale. For one thing, the tribesmen possess a highly sophisticated and lethal arsenal, and they have demonstrated their ability to use these weapons with deadly skill. More critical is the fact that FATA has become a sanctuary for Taliban insurgents and Al Qaeda militants, the home-grown variety as well as those who infiltrate across the porous border with Afghanistan. FATA has now become a menace on a global scale and President Barack Obama was right to call it the most dangerous place on Earth.

Major Cummings memoirs provide a valuable insight into the tribesmens character, in particular that of the Mahsuds who are without a doubt the most fanatical and unyielding of the Pathan tribes. It is widely believed that Osama bin Laden and his henchmen are holed up in Waziristan, which is the Mahsuds homeland. These are the reminiscences of a British soldier who spent most of his career at close quarters with the people who now offer shelter to the worlds most dangerous terrorists. The memoirs make enlightening reading for military and political leaders, historians, academics or anyone in the general public who wishes to gain a deeper understanding of this conflict zone.

Colonel Tony Streather OBE

Acknowledgements

My thanks go first and foremost to Margaret Brown, who most generously granted permission to reproduce the photos for this book from the albums of her late husband, Major Willy Brown of the South Waziristan Scouts. Of course, there would have been no book without the memoirs. Wholehearted thanks must go to Major Cummings adopted son, Ruby Mukhia, who made the typescript available to me on a trip to Darjeeling. My gratitude to my editor, Bobby Gainher, for diligently spotting the usual howlers and for his overall improvement of the text, and to Pen & Sword for taking on the manuscript. Whatever light my editorial comments may shed on the business of soldiering in Waziristan largely reflects the knowledge I gained in conversation with former Frontiersmen, Colonel Tony Streather, Graham Wontner-Smith, Major John Girling and Rodney Bennett. Lastly, thanks go as usual to my agent Duncan McAra. Had it not been for his efforts I would almost certainly remain an unpublished author.

Introductory Reminiscences

by Colonel (Retd) Kushqat ul Mulk

The four incidents recorded below by Colonel Kushqat ul Mulk, now ninety-six, a former Commandant of the South Waziristan Scouts, the unit in which Major Cumming served, convey the humour and humanity that often characterized a soldiers life on the receiving end of the Pathan jezail, or long-barrel musket. His anecdotes bring to mind a remark by the late George MacDonald Fraser, the creator of Flashman, who once said that war can also be funny.

I joined the South Waziristan Scouts (SWS) in 1941 from Singapore and subsequently served as a Wing Officer, Wing Commander and Second in Command until 1946 when I was posted to my army battalion. In 1946, I went back to the SWS as its Commandant. It may be instructive for the reader to learn of a few episodes I experienced while serving in the SWS.

While travelling to Ladha in a convoy of two armoured lorries, the leading truck in which I was sitting in the front seat, while going around a bend, tumbled into the river. It was just below Mairobi village, short of Makin. The village of Mairobi belonged to the Shabi Khel tribe whose head, the notorious Mullah Powindah, had in the past given us a rather tough time. While the troops in the second truck took up positions on the hills above the road, the JCO in my truck and I collected all those injured in the fall and we didnt really know what to do next. In the meanwhile the Shabi Khel tribesmen from Mairobi ran down to the fallen truck and took great pains to pull it out of the river and place it on the road facing towards Ladha. I mention this as an example of Divine Mercy and also to shed some light on people who may otherwise have opposing views, but who were willing to extend help in a tricky situation.

While in Ladha post we received orders to demolish a tower across the river where a notorious hostile tribesman had been hiding. It took us nearly a month to issue warning notices to the villagers, through the political authorities headed by tehsildar Gul Mohammad. On his assurance that the village was now ready for the shelling operation, the guns were ordered to direct their aim at the tower only. After several shells were fired at the tower I gave up the operation, thinking it to be a futile exercise because of the small size of the one tower, and went off to the officers mess for a drink. I had barely finished my first drink when news came in that the tower had fallen and only then did I realize that our artillery shells had been on target. We always took great pains to pinpoint our target and avoid the kind of collateral damage that some find acceptable in current operations.