The HAYMAKERS

2000 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, write to the Minnesota Historical Society Press, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

www.mnhs.org/mhspress

Manufactured in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

International Standard Book Number

0-87351-394-0 (cloth)

0-87351-395-9 (paper)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hoffbeck, Steven R.

The haymakers : a chronicle of five farm families / Steven R. Hoffbeck.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 0-87351-394-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-87351-395-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-87351-736-2

1. HayHarvestingMinnesotaHistory.

2. FarmersMinnesotaHistory.

I. Title.

SB198.H576 2000

633.2'085'09776dc21

00-033930

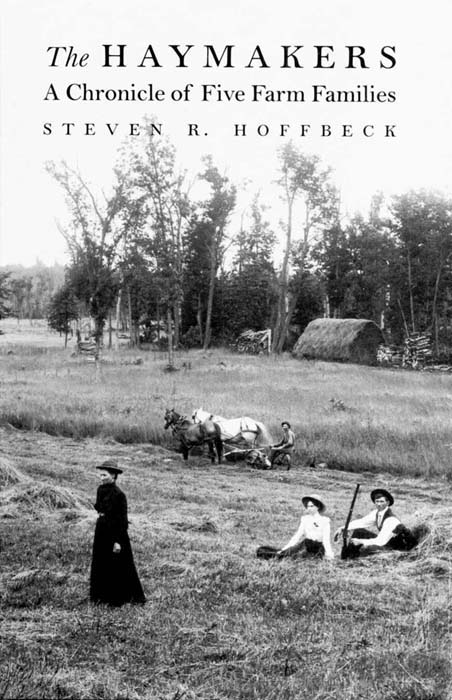

Title pages: Family mowing and raking hay in Morrison County, about 1900.

This book is for

Dianne,

for my children, Leah, Katie, Mary, and John W.

for my mother, Alvina Elsie Emilie (Engel) Hoffbeck

and in memory of

Raymond Peter Hoffbeck and

Larry William Hoffbeck

The HAYMAKERS

What is a farm but a chapter in the bible almost? Pull out the weeds, water the plants; blight, rain, insects, sun,it is mere holy emblem from its first process to the last.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, 1836

The HAYMAKERS

Mowing

There was never a sound beside the wood but one,

And that was my long scythe whispering to the ground.

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself;

Perhaps it was something about the heat of the sun,

Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound

And that was why it whispered and did not speak.

It was no dream of the gift of idle hours,

Or easy gold at the hand of fay or elf:

Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak

To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,

Not without feeble-pointed spikes of flowers

(Pale orchises), and scared a bright green snake.

The fact is the sweetest dream that labor knows.

My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make.

ROBERT FROST

Prologue

Dad posed with the combine that shredded his shirt.

We always kept track of close calls on the farm. It was Dads way of teaching us to be careful. Once, when I was still too young to remember, the combine caught his shirttail in a moving belt. Because he was strong and the shirt was cotton, it ripped and he wasnt hurt, but what if it had been thick denim? Mom took a picture as a reminder of how close he had come, a permanent image in the family photo album from that time on. The picture appeared next to snapshots of birthdays and anniversaries: Dad, younger than any of us ever knew him, bare-chested but for shreds of his ribboned workshirt dangling down to his waist. He stands posed beside the combine: one hand in his pocket, hat tipped slightly to the sidepositioned next to the exposed belt and sprocket that nearly pulled him in. His face is clenched in a grimace, but his chest is strong and unharmed.

The lesson was clear: watch out for that machine; watch your step, your hands, and your feet around the combine, the hammer-mill grinder, the mowing machine, the corn picker and the corn sheller, the silage blower and the haybale elevator. Be careful that you dont get your hand pinched hooking up the hayrack to the tractor hitch. Move with caution, every day, on every inch of the Hoffbeck farm.

We were taught to be especially careful around moving parts. The worst I faced was the power-takeoff (PTO) shaft we ran from the tractor to the hammer-mill to grind corn and oats into prime feed for the cows. It was just a bare PTO shaft, no shields, parked by the feed room. I took care to climb up the tractor, stepping past and over the shaft to get to the seat, where I cranked the throttle up to grinding speed. I always looked and stepped wisely to avoid it on the way down, careful to the point of hugging, literally, the tractors fender. Everyone feared the PTO, for everyone had heard of someone who had been caught. I didnt know how it killed someone, but I believed it was awful. These are the fears of farmkids.

In late November 1968, the worst of those fears was realized. It had already been a tough fall for Dad; the autumn skies brought too much rain and the soybean fields were too wet to harvest in September. The rains continued, and the beanfields were still too wet even through all of October. Finally in November, after the ground had frozen, Dad could work with the combine in the field, but it was so cold that he had to wear more warm clothes than usual. Whether from the fatigue of the drawn-out harvest or from the frustration of working with an aging combine-harvester, my dad made a mistake on the afternoon of the nineteenth, and somehow he got his bulky clothing caught in the PTO shaft.

My mom prepared an afternoon lunch for us kids to eat when we got home from school, wondering why Dad hadnt walked home for coffee at four oclock like he usually did. She finally went through the grove on foot to see what was keeping him. His body had been wrapped up tight in the twisting of his clothes by the PTO shaft, and he had suffocated. I was at basketball practice, in town, when my mom ran home to call an ambulance. They came and cut him from the mechanical grip of the combine, but he was dead on arrival at the Redwood Falls hospital. When I got home, my sister Ane Marie was the only one there waiting for me, tears on her face.

Daddy died. That was all she said.

In the silence of the morning following the accident, and with none of us going to school that day, I went out to the north of the grove to look at the place where it had happened. Frost hung on the tree branches. It was 7:30 and the school bus passed by on the gravel road going north, past the end of the driveway where I usually waited. I watched the bus go without me, wishing that I could go too, that somehow this could be a normal day. Searching the harvested rows of beans, I could find only traces of what had happened the day before. The old combine had been towed away, but I could see where Dad had died, for there were bits of his clothing, blue denim and white scraps of waffled long underwear, only a few icy drops of blood.

It was the combine, the same machine in the photograph, that killed him. The image was supposed to be a warning to us, not a prophecy. His death made that picturethe relief of a close calltoo hard to look at anymore. It has stayed in the family album, in my moms closet, until now.

Before the mower arrives, a field of timothy grass is green and alive, leaves waving in the morning breezes. Meadowlarks sing their early-summer songs, field mice are safe in their underground burrows, and a fox lurks by the fence line. Grasshoppers and crickets leap in the tall grass. A hawk stares from a nearby telephone pole.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.