Contents

Guide

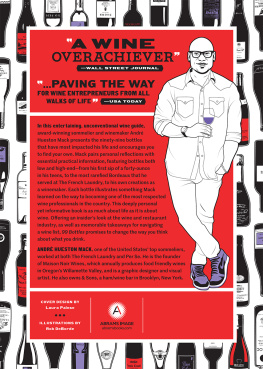

John Mack

Former CEO Of Morgan Stanley

Up Close and All In

Life Lessons From a Wall Street Warrior

To the immigrants

INTRODUCTION

I want to tell you about two career-defining conversations during my forty-three years on Wall Street. One took place in 1992 with a Morgan Stanley senior trader. It was about his breakfast sandwich. The other was in 2008 with the three most powerful people in the US economy. That was about my refusal as the CEO of Morgan Stanley to sell the firm for two dollars a share.

Each reveals different facets of my personality. I am compelled to stand up for people who dont have power. I also tell people the truth, no matter the consequences.

The breakfast sandwich story has passed into Wall Street lore. On my way to an 8:00 a.m. meeting, I saw a deliveryman standing at the elevator bank. When the meeting was over, he was still there, holding a paper bag. Werent you here thirty minutes ago? I asked him.

Yeah, he said.

Have you called the guy?

Twice, he told me.

Give me his number.

I snatched the slip of paper he was holding, walked over to the phone, and dialed the guys extension. This is John Mack. Get out here and pick up your breakfast. I was head of the Operating Committee at the time and a few months away from being president. When the employee appeared, I tore into him. Who do you think you are? This guy is trying to do exactly what you do: make a living. When you keep him waiting, youre taking money out of his pocket. Do this again and Ill fire you.

This story is about how you treat people. To me, we all have equal value, no matter what our job or how much money we have in the bank. I demanded that my employees do the right thing whether they were dealing with a CEO, a colleague, or somebody from the deli around the corner. Confronting the senior trader was not me losing my temper at a subordinate several rungs below me. It was a calibrated decision to send a message about the kind of behavior I wouldnt tolerate. Sometimes I had to be tough to get my message across.

Wall Street attracts a certain typehypercompetitive, superaggressive people who want to make a lot of money; people who are 100 percent convinced theyre smarter than everyone else in the room and are hell-bent on proving it. As a general rule, if youre the sort of person who wants to help others, you become a doctor or a teacher, not a trader or an investment banker. I was determined to convince them that the best way to go about their work every day was to consider the collective benefits of their actions before they thought of their personal benefits.

In other words, I wanted to build a culture where these driven Wall Streeters pulled together as a team, and calling out an inconsiderate trader was one of the ways I did it.

Another career-defining moment occurred when I hung up the phone on Henry Hank Paulson, Ben Bernanke, and Timothy Geithnerrespectively, the US Treasury secretary, the Federal Reserve chairman, and the New York Federal Reserve Bank president. It was a reckless act during a period when Wall Street and Main Street were engulfed in the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Morgan Stanley was on the brink of collapse. But I refused to sell out the firms forty-five thousand employees and its shareholders. It was those ten minutes on the phone that convinced me I have something valuable to teach others.

You may not have to defy the US Treasury secretary. But at some point in your life, you will have to make difficult decisions when all eyes are on you. The essence of leadership is making decisions under pressure, whether youre running a business, raising a family, or simply living your life. Making the hard calls when you have no idea of the outcometaking the risk, putting yourself out therethats when you prove your mettle.

During more than four decades on Wall Street, I learned a lot about managingand mismanagingpeople, both in times of crisis and the ordinary day-to-day. I see too many people call themselves leaders without truly leading. They shy away from confrontation and put off making hard decisions. They believe they have all the answers and surround themselves with people who tell them only what they want to hear. They demand that employees do things they wont do themselves. They dont learn to praise as easily as they learn to criticize, and they believe that money is the only motivator. These faux leaders take themselves too seriously, overreact to bad news, and expect others to do things exactly the way they would do them, failing to appreciate that sometimes a fresh approach can yield better results.

On one level, this is a book about how a talker became a listener, a listener became a better person, and a better person became a better leader. My self-confidence came naturally, but I had to learn how to foster confidence and collaboration in others, and to get groups of people to produce substantially more than they would as individuals. I saw firsthand that leaders are made, not born. Leadership is a discipline, something you practice. Like salesmanship, some learn it more easily than others, but it can be learned.

Over thirty-four years at Morgan Stanley, my goal was to build the strongest and most productive team on Wall Street, and Im proud to say I believe I succeeded. We anticipated trends before other firms, achieved record profits, and survived daunting crises. Morgan Stanley also transformed into a global juggernaut during this time, opening offices in forty-three countries and growing from three hundred employees in 1972 to more than fifty thousand employees today.

Ill share the strategies and philosophies that drove my success within the larger story of my journey from a small North Carolina mill town to a fortieth-floor corner office on Wall Streeta quintessentially American arc. At the turn of the last century, my grandfather and father came to this country from a tiny village in southern Lebanon and settled in Mooresville, North Carolina, a one-stoplight town where almost everyone was Baptist. We were different. Both my parents were devout Catholics and spoke Arabic at home. There was no talk about the financial services industry around the dinner table, and the only securities in town were shares of the local bank. My dream was to open a menswear shop in North Carolina with my cousin.

In college, everything I thought I knew about myself turned out to be wrong. I arrived at Duke University on a full athletic scholarship as an all-state football player. I was a standout in a high school senior class of ninety students. Not at Duke. I almost flunked out. My time on the football field was worse. I went from being a star to riding the bench. Then my father passed away, and, needing to pay my own way through my senior year, I took an entry-level job in the back office at a local securities firm.

It wasnt long until I realized my future was in New York. I arrived in Manhattan in 1968. It was a transformational time. The role of preeminent banks like Morgan Stanley had always been to advise blue-chip clients like IBM and AT&T. They didnt participate in what they considered to be the grubby world of trading stocks and bonds. But in the early 1970s, as deregulation and new technology changed the playing field, scrappy trading houses like Salomon Brothers and Merrill Lynch disrupted the long-standing business model by aggressively poaching clients. Overnight, sedate Wall Street became fiercely competitiveand I had a front-row seat. In the coming years, I developed a titanium-strength stomach for risk, pressure, and big personalities. The raucous, smoke-filled bullpen where I started immediately felt like home. In the pages ahead, youll learn not only how Wall Street transformed in the past five decades but how to stay ahead of the curve in a continually evolving industry.