Preface

A few years ago, at a friends dinner party, I was introduced to the proprietor of an antiquarian bookshop in Toronto called the Monkeys Paw. Specializing in what its owner deems arcane and absurd, the Monkeys Paw is a curious place. Many around town know it as the home of the Biblio-Mat: a used-book vending machine reminiscent of a 1950s-era refrigerator. Drop a toonie (a Canadian two-dollar coin) into its slot, and the Biblio-Mat starts to buzz. Then a bell dings and out pops a random book on some obscure subject.

I had browsed around in the Monkeys Paw before and had even chatted with its ownerboth of us unaware we had a mutual friendbut I never bought anything from him. As much as I admired his strange books, an ingrained backpackers ethos of minimalism kept me from acquiring any of them. So when small talk over cocktails at the dinner party inevitably pivoted to the And-what-do-you-do? question and I told the bookseller that Im a religion professor who studies the ancient Christian martyrs, I was only politely interested when he clapped his hands together in delight and announced that he had just the book for me. But as it happened, he did. His book was the impetus for this one.

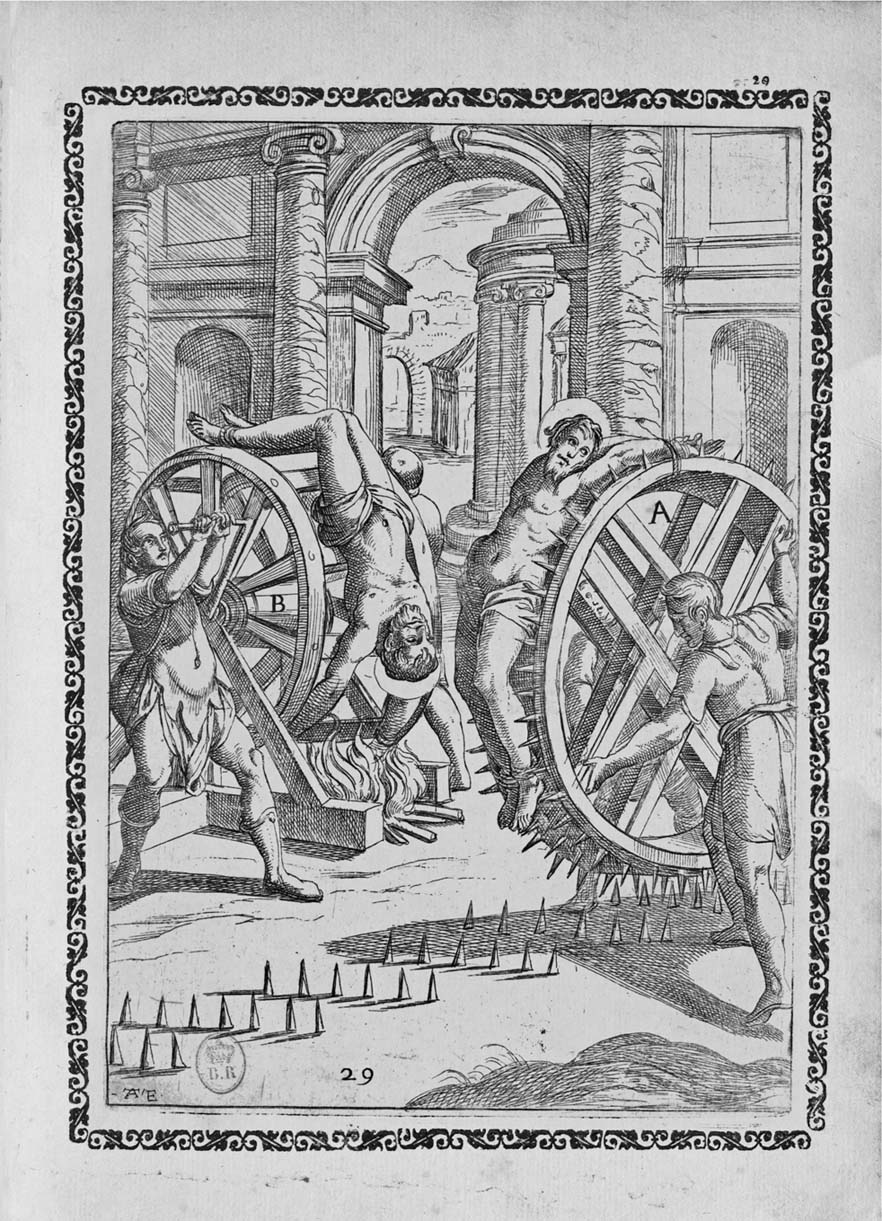

On display in his storefront window was a weathered English reprint of an elaborately illustrated volume that had first been published in Italian in the sixteenth century. Its dun-colored pages were propped open to an image of a man tied to a wheel that is about to be rolled down a road of iron spikes (see fig. 1). The books other illustrationsdozens of facsimiles of the original copperplate engravingsare just as grisly. One man is about to be crushed in an olive press. Another stands as a human brazier forced into offering red-hot coals of incense to a pagan idol with his bare hands. A third cowers on one knee as the schoolboys gathered around him prepare to stab him with, of all things, their pens the pointy styli that Roman students used to employ to scratch letters onto wax-covered tablets.

FIGURE 1. Martyrs being tortured on wheels, designed by Giovanni Guerra with engraving by Antonio Tempesta for Antonio Gallonios Trattato de gli instrumenti di martirio, e delle varie maniere di martoriare usate da gentili contro christiani (Rome, 1591).

Despite all these theatrical and innovative forms of violence, the books engravings lack blood and gore. Their violence is instructive, not gratuitous. Various augers, cauldrons, wheels, chains, pulleys, and hacksaws are shown in action but usually frozen in the immediate moment before their use. This does not make these images any easier to see. Anticipated horrors can be more cringe inducing than already completed scenes.

Set as they are against a generic backdrop of porticoes and archways in an otherwise empty classical city, the horrors I found displayed in the booksellers window unfold in an imagined world. The men and women about to be on the receiving end of a torturers tool are anonymous. Clad in identical loincloths, they gaze off impassively toward some distant horizon. They could be anyone. And they are almost never pictured alone. Those being tortured are presented together, either in pairs or in threes or fours, with others who are undergoing similar sorts of trials. Those steeling themselves to have a limb chopped off are on one page, those being stretched or hung are on another, and those about to be branded or burned are yet elsewhere.

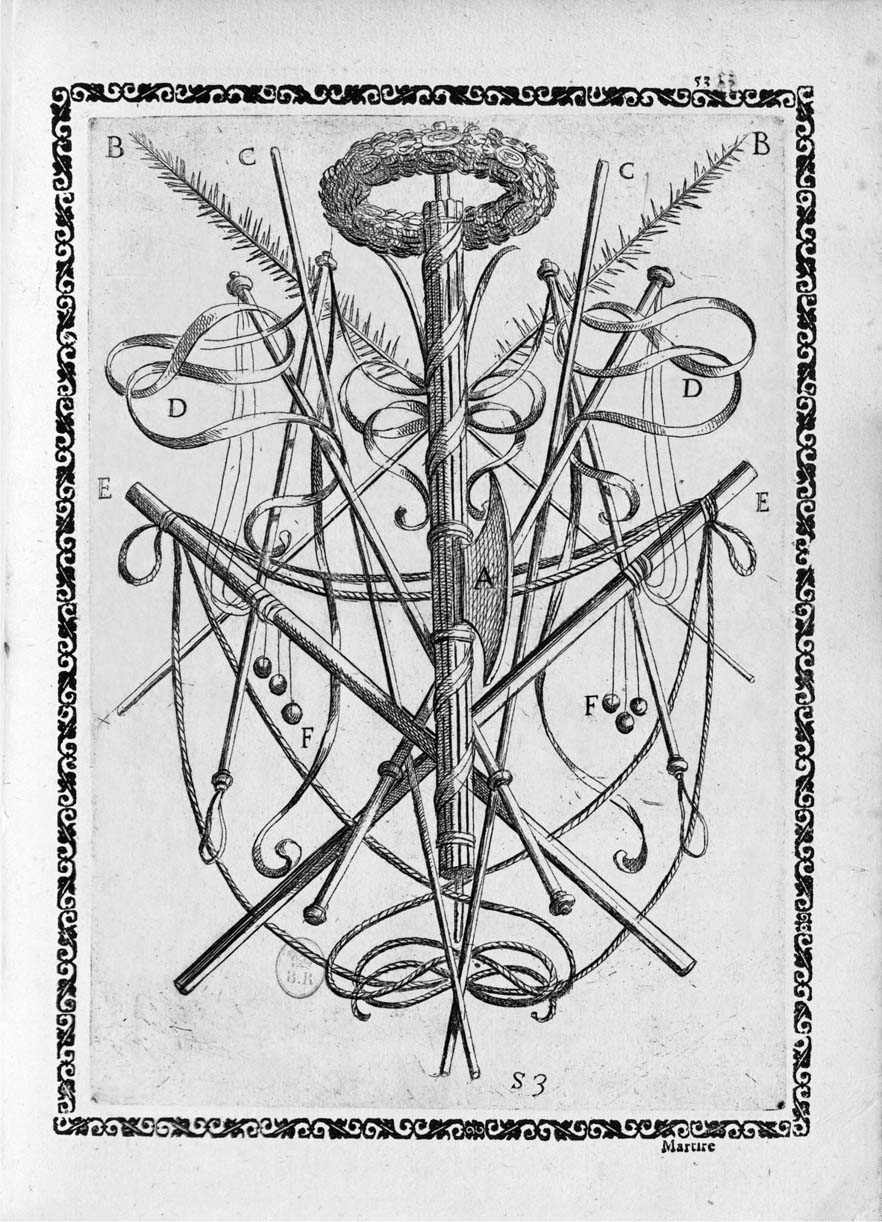

Across twelve systematically organized chapters, the book collects, classifies, divides, and subdivides every conceivable way that early Christian martyrs might have had their flesh torn, butchered, or burned. In celebrating the hardware that won the martyrs their paradoxical victory over death, a few of the engravings present just the tools of torture aloneno martyr in sight. At first glance, one especially well-curated ensemble looks like a floral motif ready to be replicated on a roll of wallpaper (see fig. 2). But look more closely at its frilly ribbons and palm fronds and see that they adorn a collection of cudgels, ropes, and blades. I took the book straight to the register without checking its price.

FIGURE 2. Arrangement celebrating some of the tools used to torture and kill Christian martyrs, designed by Guerra with engraving by Tempesta for Gallonios Trattato de gli instrumenti di martirio .

Once I got my new prize back to my office, it took little sleuthing to figure out what it was. The Treatise on the Instruments of Martyrdom, and the Various Manners of Martyrdom Used by Gentiles against Christians was originally published in Rome in 1591. Its text was written by Father Antonio Gallonio, a Catholic priest and scholar of ancient Christian martyrdom, while its engravings were designed and executed by artists from Florence and Modena. What I had bought was a 1903 English translation, competently done by a British academic. Yet oddly, there was not much in the books front matter to explain why it had been written. No translators preface, no scholarly introduction, nothing except for a publishers note cryptically signed with the initials C.C. And this is where things got weird.

The initials, I soon discovered, were those of Charles Carrington, the pseudonym of a Paris-based publisher better known for books like the Beautiful Flagellants trilogy by Lord Drialys, a fictional English aristocrat who supposedly traveled to Boston, New York, and Chicago in search of American women eager to be spanked by a peer of the realm. In other words, Charles Carrington was a publisher of late Victorian porn. But even though sadomasochistic and other erotic fiction was his bread and butter, it seems that Carrington occasionally dabbled in somewhat more pensive pursuits to lend his publishing house a veneer of respectabilityand given the constraints of the age, perhaps legality too.